Gwerz Skolvan

-

Genre :Music from France

-

Tradition :Brittany, Gwerz

-

Piece name:Gwerz Skolvan

-

Specifics:Gwerz

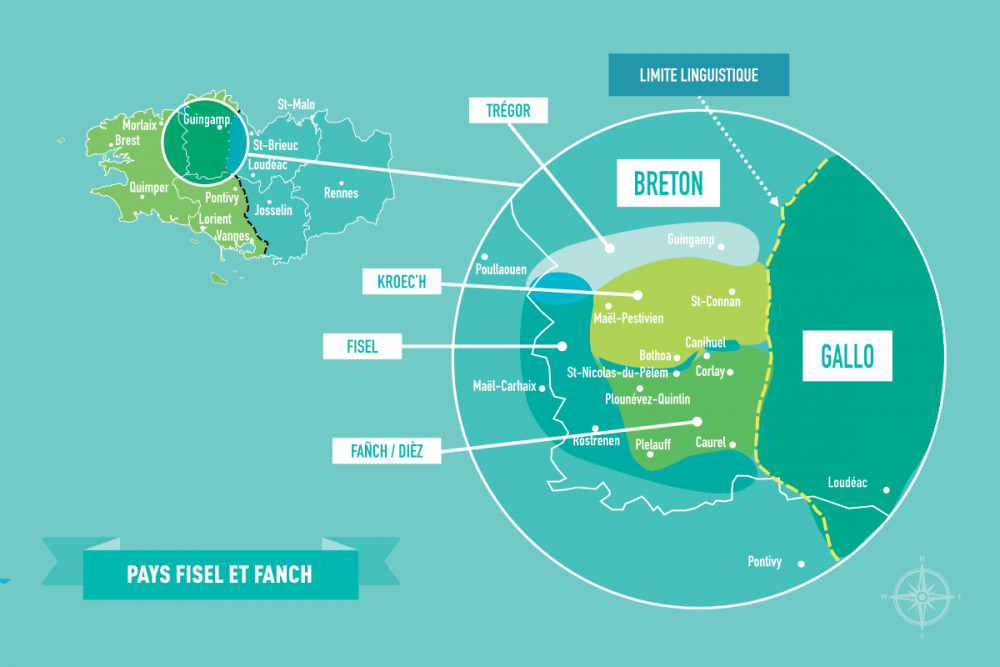

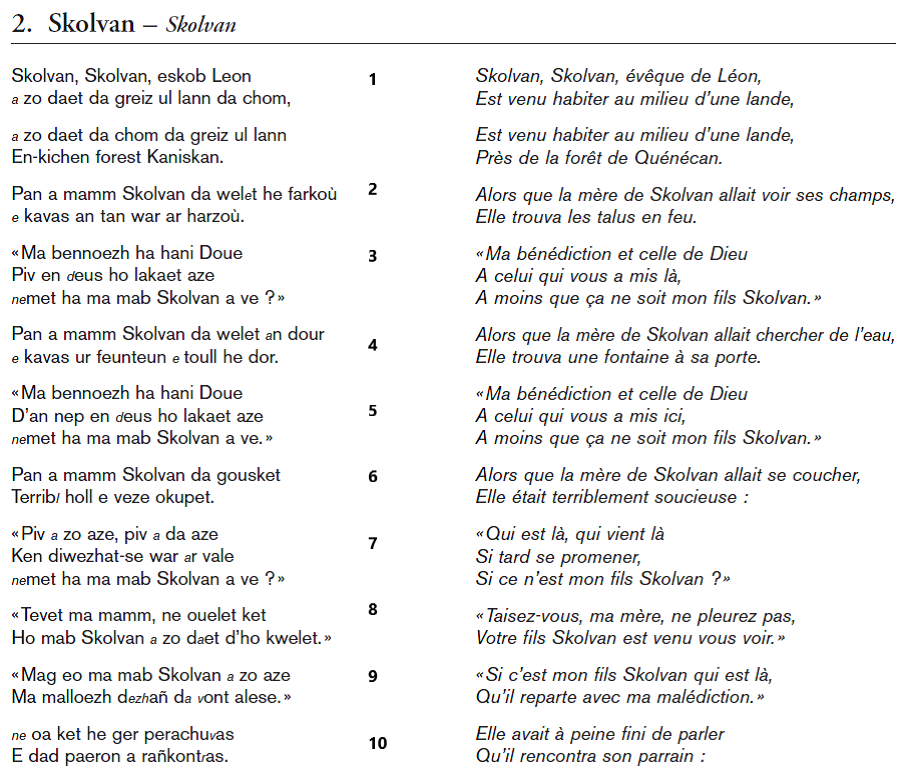

Two versions of a song - the gwerz of Skolvan -, sung in the Breton language (Cornish) on the same melodic line by Madame Bertrand, are presented and studied here. The recordings were made by Claudine Mazéas, the first (work 1) in 1959 in Canihuel at Madame Bertrand's, the second (work 2) in Saint-Nicolas-du-Pélem at La Piscine, the pool bar run by her son Guillaume , on an unknown date.

In “mirror” is presented a more succinct analysis of two interpretations of Sulian’s gwerz, one by Madame Delaure and collected by Yann-Fañch Kemener, the other by myself and the Mallakastër polyphonic ensemble.

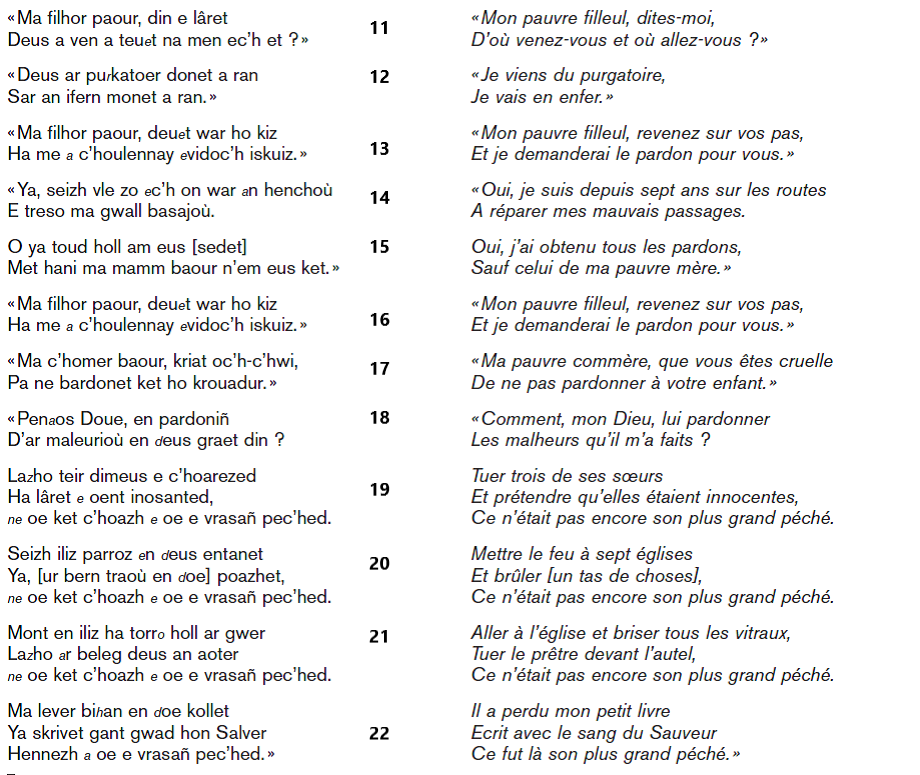

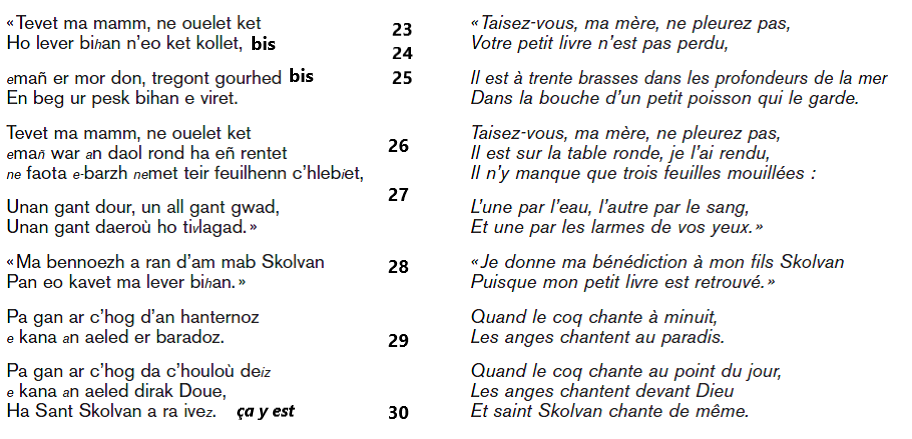

Other recordings of these two gwerz, collected from other 20th century performers or performed by contemporary artists, complete this study.

Work 1: Gwerz by Skolvan, performed by Madame Bertrand. Recorded at her home in Canihuel on January 18, 1959 by Claudine Mazéas. Courtesy of Dastum.

Note that this map is a modern and simplified choice of much more complex historical and social realities, as we show below with regard to the Fañch country.

To give a simple definition, a gwerz is a Breton song which tells a story, from a news item to a historical or mythological epic. We will return to how to define a gwerz later.

The gwerz of Skolvan in its interpretation by Madame Bertrand is an emblematic song in more than one way, and I have chosen to highlight its specificities here for different reasons.

As is generally the case in Brittany, it is the poetic and historical sides of this text which have been particularly highlighted. The gwerz of Skolvan is one of the rare songs from Brittany for which a historical dating of the text can be established: Donatien Laurent, who has carried out the most complete study of it, cites the 12th century as the date of the first transcription of the text ( see his article published in 1971 in the journal Ethnologie Française and the summary of the latter in Cahier Dastum n° 5 devoted to the Fañch country [pays Fañch]- these sources as well as others are also accessible in the section “The musical universe: The popular musicians of Lower Brittany[L'univers musical : Les musiciens et musiciennes populaires de Basse-Bretagne]

The Skolvan gwerz was recorded during several collections, it was also the subject of research which we will discuss. The text of the Skolvan gwerz has been published in numerous works. The song has also been performed and recorded by many musicians: we will return to these interpretations later.

Above all, the masterful interpretation delivered by Madame Bertrand contributed to the fame of the Skolvan gwerz as well as that of its interpreter.

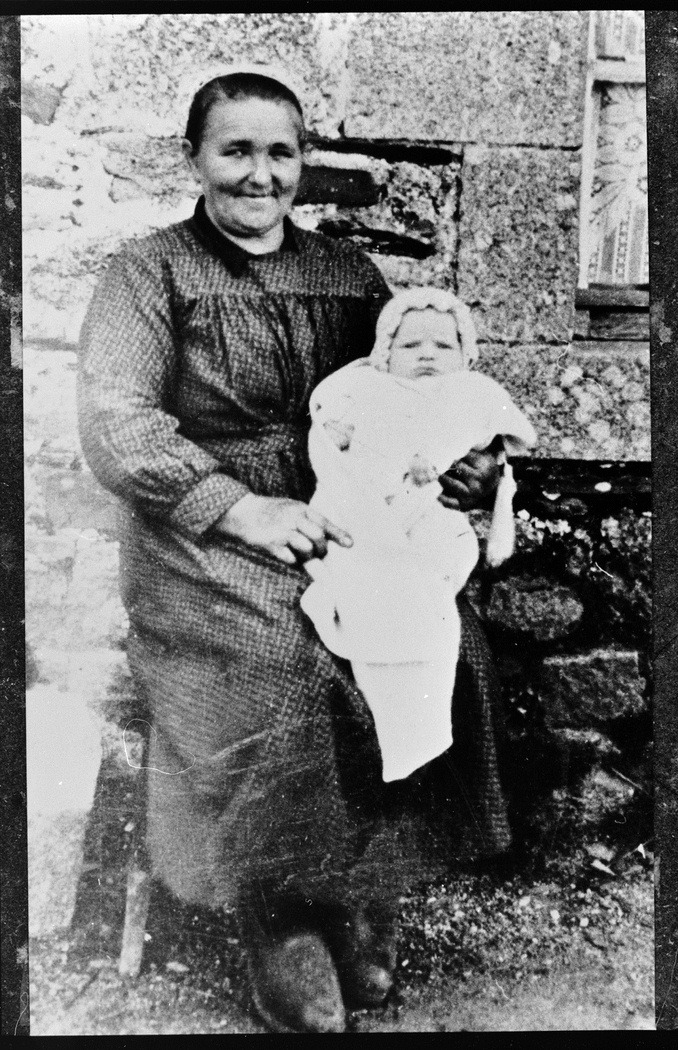

Madame Bertrand is and was considered a very great singer. Born Marie-Josèphe Martay (Madame Bertrand by her married name), nicknamed Josée Ar C'hoad, that is to say Josée Du Bois in the literal sense, she worked as a clog maker. This is why she lived for several months of the year in a hut, in the middle of the forest, on the construction sites where the clog makers worked.

Madame Bertrand and her grandson Guy in 1935 in Canihuel. ©Paulette Simon-Bertrand

For almost all singers today, Madame Bertrand has become a reference. According to Marthe Vassallo (2008): “Today's singers only knew Marie-Josèphe Bertrand, who died in 1970, through recording - which means that for many of us she is forever “Madame Bertrand”, as they say Callas”.

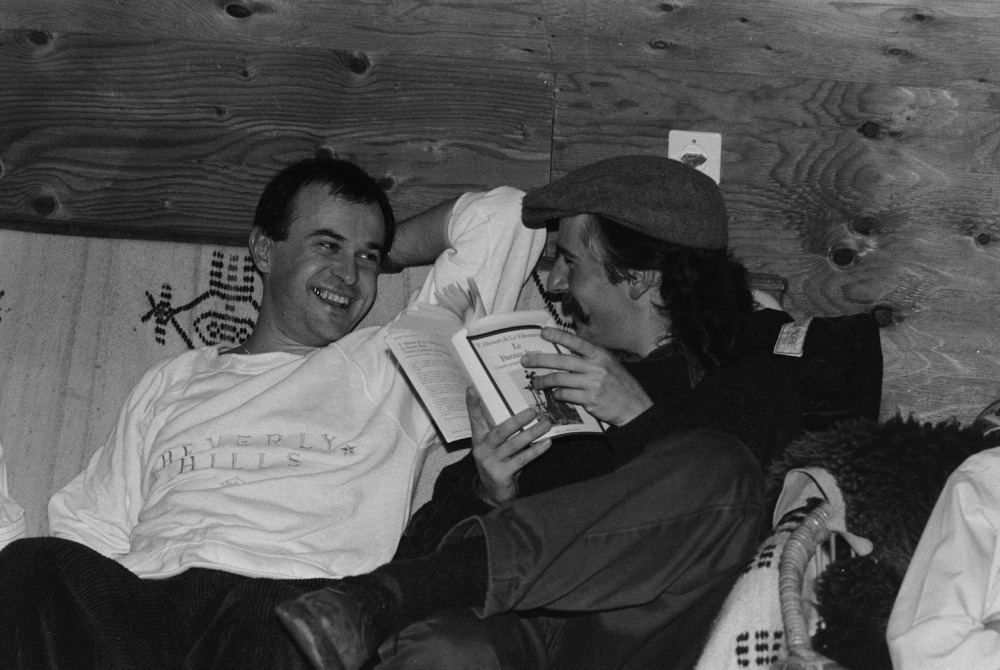

Yann-Fañch Kemener and I called her “Mother Bertrand” with due respect.

Yann-Fañch Kemener (on the left) and Erik Marchand in 1989. Photo Robert Bouthillier © Dastum

Yann-Fañch Kemener (on the left) and Erik Marchand in 1989. Photo Robert Bouthillier © Dastum

We have two versions of this song performed by Madame Bertrand in Cornish Breton. The first, referred to here as "work 1," was recorded in 1959 by Claudine Mazéas in Canihuel at Madame Bertrand's home. The second was also recorded by Claudine Mazéas, in Saint-Nicolas-du-Pélem at La Piscine, the bar-pool run by Guillaume Bertrand (Madame Bertrand's son): this is work 2.

Work 2 : La gwerz de Skolvan performed by Madame Bertrand, second version. Recorded by Claudine Mazéas in Saint-Nicolas-du-Pélem. Courtesy of Dastum.

In Breton music repertoires, it is possible to find the same song performed by the same artist to different musical themes. Madame Bertrand used this technique in other cases, such as in her interpretations of Ywan Gamus's gwerz, for example, as we shall see.

But here we have the opportunity to compare these two versions of Skolvan's gwerz in the same key and thus highlight their differences and similarities.

These two versions are quite similar, but we wish to bring out their modal character by studying the variations in the melodic line, the rhythmic form, and the articulation between the text and the melody.

Various people contributed to the implementation of this study and we would like to thank them here: Nicolas Adell and the journal Ethnologie Française, Jérôme Bourgeois (archives of Yann-Fañch Kemener), Simon Cohen (photograph of Yann-Fañch Kemener), Gwenn Drapier (Dastum archives), Ronan Pellen (transcriptions on scores), as well as Claudine Mazéas.

Tonioù versus Kanaouennoù

Un des éléments marquants du phénomène parfois qualifié de folklorisation est que l’on trouve des versions différentes d’une même oeuvre musicale (instrumentale ou vocale) d’un interprète à l’autre dans une zone géographique parfois restreinte, et plus rarement chez un même interprète. En Basse Bretagne ce phénomène est encore amplifié.

One of the striking elements of this phenomenon, sometimes described as folklorization, is that different versions of the same musical work (instrumental or vocal) can be found from one performer to another, sometimes within a limited geographical area, and more rarely from the same performer. In Lower Brittany, this phenomenon is even more pronounced.

It is even possible to consider that, in most cases, there exists a repertoire of musical themes that could be called "timbres" (according to Jean-Baptiste Weckerlin, a "timbre" or "pont-neuf" in the 19th century referred to a well-known motif or tune to which songs were set, in *La chanson populaire*, Paris, Firmin-Didot, 1886).

To designate these themes, however, we prefer to use the term tone (plural: tonioù), while kanaouenn (plural kanaouennoù) designates a sung poem.

To our knowledge, Madame Bertrand sings the gwerz of Skolvan only in the key we hear here. This is unlike other kanaouennoù, such as the gwerz Ywan Gamus, which she sings in at least two keys, as we invite you to listen to here:

Ywan Gamus, or Gwerz Ywan Gamus (long version), performed by Madame Bertrand. Recorded by Claudine Mazéas in Canihuel in 1959. Track 5 from the album Marie-Josèphe Bertrand. Chanteuse du Centre-Bretagne, Dastum, 2008

Ywan Gamus, or Gwerz Ywan Gamus (short version), performed by Madame Bertrand. Recorded by Claudine Mazéas in Canihuel in 1959. Track 6 from the album Marie-Josèphe Bertrand. Singer from Central Brittany, Dastum, 2008.

Different tones for the gwerz of Skolvan

We have juxtaposed the gwerz of Skolvan sung by other singers in more or less well-known tones, one of which has been popularized under the name "Ker Is." We hear this tone in the Gwerz Ker Is, which we offer here in the version by Jean-Marie Long:

Gwerz Kêr Is, performed by Jean-Marie Long; recorded by Michel Querrou in the 1960s. Track A6 of the vinyl record Le cercle celtique de Poullaouen. Gavottes de Bretagne - Kan Ha Diskan, Disques Vogue, CMDINT 9659.

It should be noted, however, that this Ker Is tone is also used to sing the gwerz of Skolvan and the gwerz of Sulian, as we hear in these three performances:

Gwerz Skolvan, performed by Germaine Le Rolland, recorded by Donatien Laurent on December 27, 1967, in Carhaix-Plouguer. © National Archives

Gwerz Skolvan, performed by Jean-Louis Rolland, recorded by Yann-Fañch Kemener on September 20, 1979, in Carhaix-Plouguer. Published in Yann-Fañch Kemener's travel journals (1996, CDs 1-5).

Gwerz Sulian, performed by Germaine Le Moullec, recorded by Charles Le Gall in Rostrenen on April 28, 1968. © Charles Le Gall

Madame Bertrand's Interpretation

Regarding the transcription and notation, I use my own system of notating scale degrees, while still providing the Latin names of the notes. Indeed, the language and representation of European classical music solfège on the score do not seem entirely appropriate to me, as I will explain:

Notes for reading the analysis of the melodic lines:

- The degrees noted in parentheses are those that are not always expressed

- The indication ½b (half flat) indicates a degree (here, E or B) between a flat and a natural

- The arrows indicate that a note is higher or lower than the written degree

Work 1 (above) is sung in C almost sharp (reference A440).

The second version (work 2, below) is sung in A.

The melodic form primarily used by Madame Bertrand is a-b-a’, except for the first verse where the form is always a-b-a-b-a’, in both versions. The form a-b-a-b-a-b-a’ also appears several times in both versions.

a mi½b fa sol fa mi½b (mi½b) fa fa mi½b͜

a E½♭ F G F E½♭ (E½♭) F F E½♭ D C

b (do) ré mi½b fa fa mi½b ré do sib↑

a’ (sib↑) mi½b fa sol fa mi½b fa fa mi½b͜ ré do

Soit dans la notation des degrés :

a 3° 4 5 4 3° (3°) 4 4 3͜°2 1

b (1) 2 3° 4 4 3° 2 1 7-↑

a’ (7-↑) 3° 4 5 4 3° 4 4 3͜°2 1

Phrase b is always syllabic.

Case of atypical stanzas a b a b a' and more:

The song begins with a grouping of two lines. These are not assonant in the same way: the first two in on/om, the following two in ann/an.

In my opinion, there is no particular explanation for this phenomenon other than the performer's habit.

Later in the performance, we find truncated forms, such as ellipses or a compressed form: ab… a(or a’)b… aba’.

We can hear this "compressed" form in the gwerz Ywan Gamus performed by Madame Bertrand, where in the 3-phrase version, alongside the general form abc, we find forms ab... ab… abc:

Perspectives on the Skolvan Gwerz

Dialogues

Testimony of Georges Cadoudal

Georges Cadoudal, interview with Erik Marchand. Huelgoat, August 5, 2020. ©Drom

Georges Cadoudal is one of those to whom we owe the opportunity to hear the Skolvan gwerz today, performed by Madame Bertrand. After meeting her, he brought Claudine Mazéas to meet her and record her performance.

We asked him to share his memories here, in an interview conducted at his home in Huelgoat on August 5, 2020.

He recounts to Erik Marchand his meeting with Madame Bertrand, evoking her knowledge, talent, and strong personality.

Georges Cadoudalalso discusses the work of Claudine Mazéas and how the recording took place at Madame Bertrand's home in Canihuel.

Finally, he shares his perspective on Madame Bertrand's social and musical standing in the 1950s.

A musician of the same tradition

Marthe Vassallo's viewpoint

Marie-Josèphe Bertrand's Skolvan

by Marthe Vassallo

Learning and transmitting through memory and emotion

Other Interpretations of the Gwerz Skolvan

The Gwerz Skolvan has inspired many musicians, and we have already shared some of them, sung in the "Ker Is" style.

Here we offer other interpretations: some are from field recordings, others are individual or collective creations.

Field Recordings

Interpretation of the Gwerz Skolvan by Jeanne L'Afféter, preceded by a discussion with Donatien Laurent.

Recorded by Donatien Laurent in Trébrivan on February 15, 1968. © Tanguy Laurent / National Archivesnterprétation de la Gwerz Skolvan par Jeanne L'Afféter, précédée d'une discussion avec Donatien Laurent.

Enregistrement effectué par Donatien Laurent à Trébrivan le 15 février 1968. © Tanguy Laurent / Archives Nationales

Jeanne L'Afféter - Gwerz Skolvan. 1968

Discussion about versions of Gwerz Skolvan by Donatien Laurent and Germaine Le Rolland

Recording made by Donatien Laurent in Carhaix-Plouguer on December 27, 1967. © Tanguy Laurent / National Archives

Gwerz Skolvan by Donatien Laurent and Germaine Le Rolland, 1967.

Erwanig ar Skolvan, by Louise Le Grouiec

Recording made by Yves Le Troadec, released on the album Gwerzioù ha sonioù Bro Dreger, Living Tradition of Brittany collection, vol. 13 © Dastum.

Erwanig ar Skolvan, by Louise Le Grouiec

A cappella performance by Yann-Fañch Kemener, recorded in Maël-Pestivien on October 23, 1993:

Yann-Fañch Kemener, Gwerz Skolvan, 1993. © Jérôme Bourgeois

Here is Catherine Guern's version, recorded in 1961 by Donatien Laurent:

Gwerz Stolvennig. Catherine Guern © ArMen/Dastum

Interpretations et creations

Yann-Fañch Kemener has sung the Gwerz Skolvan on numerous occasions and has offered various reinterpretations, for example with the group Skolvan in 1994:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPdHmGEg0dM

Based on, firstly, the "double version" by Madame Bertrand and Catherine Guern, arranged by me, and secondly, a composition by Kristen Noguès, I myself sang the Gwerz Skolvan in the version that appears on the album Logodennig, 1952-2007 (disc 1, track 11) by Kristen Noguès, recorded during a concert at Le Quartz in 2007 (with Celtic Procession: Jacques Pellen, Jean-Michel Veillon, Jacky Molard, Ronan Pellen, Etienne Callac, Karim Ziad, Nguyên Lê).

Regarding this performance, what we did that day with the Gwerz Skolvan, and the encounter between modality and tonality:

Folk Musicians of Lower Brittany

It is important to understand the social and economic context of the musical practices of folk musicians in Lower Brittany during the 20th century.

You can also listen to Georges Cadoudal's testimony about Madame Bertrand.

We also provide you with various documents and bibliographical references:

- Article by Donatien Laurent, 1971, "La Gwerz de Skolan et la légende de Merlin" (The Gwerz of Skolan and the Legend of Merlin), Ethnologie française, vol. 1, 3-4, pp. 19-54.

(made available with the kind permission of the journal Ethnologie française and Presses Universitaires de France)L - Booklet (100 pages) for the album Marie-Josèphe Bertrand. Chanteuse du Centre-Bretagne (Singer of Central Brittany). Grands Interprètes de Bretagne (Great Performers of Brittany), vol. 4. Dastum, 2008.

(Courtesy of Dastum) - Dastum Notebook No. 5, dedicated to the Fañch region: Bro Fañch. Djezaoù ha Kroec'haoù, 1978.

(Courtesy of Dastum)

Contexte musical, social et historique

Brief Historical Context

History of the Skolvan Gwerz

What is a gwerz?

The term gwerz (which is masculine or feminine depending on the author; I have chosen the feminine) seems difficult to translate. It comes from the Middle Breton word guers, itself derived from the Latin versus: “towards, furrow, line of writing.”

The meaning of gwerz is close to the French word “complainte” (lament), particularly in that the forms differ. Furthermore, Breton and Francophone popular cultures have created gwerzioù, or moralistic laments, since the 19th century, which describe everyday events.

One of the differences between a lament and a gwerz is often the length of the work and the abundance of detail and local references found in a gwerz, even in the case of transcultural myths. Orpheus lived 5 km from your home, and you might even meet his descendants; your parents may have known him.

Marie Cann, Madame Kerjean, the wife of my mentor Manuel, told me that in some dialects of northwestern Morbihan, gwerz could mean news (keloù in Breton).

It was undoubtedly François-Marie Luzel (1971 [1868-1890]), a 19th-century collector, who defined the concept of gwerzioù and sonioù through his example:

“Gwerziou include epic songs, which can be subdivided into: historical songs, legendary songs, marvelous or fantastical songs, and anecdotal songs. Soniou are lyric poetry. [...] love songs, songs of Kloers or clerics [...] satirical and comic songs, wedding and customary songs, etc. Children's songs, dance songs, rounds, jabadao, passepieds, etc., must also be included.”

According to Eva Guillorel (2010), the lament and the complaint are “[…] long pieces that describe tragic local events, that show a great attention to detail in the situations described, and that generally report with great reliability the memory of precise names of places and people […]”.

In a gwerz, more than historical accuracy, the narrative structure must speak directly to the listener, so that they can feel emotions or draw parallels with their own life. Donatien Laurent, in his study on La gwerz de Skolan, reminds us of the importance of the role played by “this two-sided truth – truth of experience and truth of feelings – which is the vital principle of the gwerz” (1971, p. 29).

La gwerz de Skolvan and the legend of Merlin: research conducted by Donatien Laurent

Regarding the history of the gwerz de Skolvan, various studies have been conducted.

We are making available here, in PDF format, article by Donatien Laurent, “La gwerz de Skolan et la légende de Merlin” (The Gwerz of Skolan and the Legend of Merlin), published in 1971 in the journal *Ethnologie française* (1/3-4, pp. 19-54), with the kind permission of *Ethnologie française* and Presses Universitaires de France.

The authors of Cahier Dastum No. 5, dedicated to the Fañch region, also referred to this work, while publishing a summary of the article (pp. 43-45). We reproduce this summary below.

The gwerz of Yannik Skolan has been collected many times since 1835 (La Villemarqué, Penguern, Gabriel Milin, Luzel, E. Ernault, Le Diberder, Canon Pérennès, D. Laurent).

This allows us to distinguish two main groups of variants:

- The Léon-Tréguier versions, reworked, more marked by clericalism, and "exuding a subtle hint of the confessional."

- The Haute-Cornouaille versions, from which emerge "a mysterious atmosphere," "typical of a culture and certainly indicative of a very archaic mentality."

The interest in this gwerz is already justified by its poetic nature. For example, the mother's almost incantatory tirade in Madame Bertrand's version, or this passage from a Trébrivan version:

« Si c’est mon fils Skolvan qui est venu ici

Je lance sur lui ma malédiction.

La malédiction des étoiles et de la lune

La malédiction de la rosée qui tombe sur la terre,

La malédiction des étoiles et du soleil,

La malédiction des douze apôtres,

La malédiction de ses frères et sœurs,

La malédiction de tous les innocents ».Translation

If it is my son Skolvan who has come here, I cast my curse upon him.

The curse of the stars and the moon

The curse of the dew that falls upon the earth,

The curse of the stars and the sun,

The curse of the twelve apostles,

The curse of his brothers and sisters,

The curse of all the innocent.

The musical and poetic form reinforces this interest. Indeed, the versions from Upper Cornouaille use melodies of three musical phrases and stanzas composed of octosyllabic lines grouped into monorhymed tercets.

However, the oldest songs collected by Luzel are based on couplets in which the second line is repeated, or on tercets of octosyllabic lines ("quatrains invariably characterize compositions of a more recent style"). And, in Duhamel's collection, "between a third and a quarter of the gwerziou tunes have this ternary structure which necessitates dividing the text into tercets of short lines." "The fact that such a melodic form seems very rarely represented in the traditional repertoire of French-speaking countries leads one to wonder whether this is not an original feature of Breton song." (It is remarkable to note that this strophic form is exactly the one used in early bardic poetry from the 7th to the 9th centuries, a form that was abandoned in Wales in the 12th century.)

Beyond these musical and poetic questions, Donatien Laurent highlights "the possible connection between the Breton gwerz and a medieval Welsh text"... "however improbable such a connection may seem, the two populations only shared a common culture in the early Middle Ages and had virtually ceased to have any contact since the 12th century."

In the Black Book of Carmarthen, "usually dated to the late 12th century" and recounting events "estimated by specialists to be two or three centuries earlier" than the written text, there is mention of a "certain Yscolan" repenting of having:

"burned down a church, killed the monastery's cows, and drowned the donated book," adding that: "his penance is a heavy affliction."

Interpretations of this text in Wales present either Merlin confessing his sins to Saint Columbanus (who has become Yscolan) or, conversely, Saint Columbanus regretting before Merlin having "attacked the druids, destroyed their temples, their schools, and their books." Others, without identifying the characters, consider this poem to refer to "some incident that occurred during the Christianization of the island of Britain, pitting pagan druids and bards against the propagators of the new faith."

Previously, bards of the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries had mentioned a "Scolan or Yscolan who was said to have been guilty of stealing or burning Welsh books."

Donatien Laurent, for his part, draws a parallel between Scolan, Yscolan, and Merlin.

The "Black Book" describes Yscolan doing penance, impaled on a stake for a year and enduring "the wind at the top of the high branches of bare trees," and characterized by the color black:

"Black your horse, black your garment,

Black your head,

And black yourself, in the end, are you Yscolan?"

Now, in all the texts relating to Merlin, a figure whose physiognomy is ubiquitous in ancient Celtic insular literatures (Lailoken in Scotland, Merlin in Wales, Suibhne Geilt in Ireland), we find penance as expiation for misdeeds: responsibility for a battle, a horrific vision, the destruction of a psalter thrown into the water (a particularly serious crime given the sacred nature of books for early Christians). We also find, as in certain Breton versions and in Yscolan’s poem, the torment of the “icy wind, the snow, the storm (which) brings death through the branches of every tree.” Finally, the three names mentioned above and that of Yscolan are also linked by agony on a stake and the same “climate of despair.”

The Breton Skolan, however, is presented as a revenant. Popular belief attributes to these beings a number of traits common to those developed about wild men (Merlin, Lailoken, Suibhne Geilt): "clairvoyance... fear of the cold, dwelling in trees." Similarly, the color black (found in Breton versions with almost identical wording) "suggests a revenant," a "trait well attested in medieval literature." Furthermore, "Ifor Williams traced the name Yscolan back to an ancient Scaul, corresponding to the Irish Scàl," one of whose meanings is "phantom, spirit, ghost."

Thus, the "relationship between a very ancient literary culture and certain aspects of a recent popular culture" is highlighted. Entire verses are similar on both sides of the Channel, easily identifiable, and the difference is felt mainly because, "works of scholars, the Welsh, Irish, Latin texts" are situated in "a precise social and historical framework" (evolving from the 6th to the 7th centuries), whereas the Breton gwerz, on the other hand, "has eliminated history" to develop only the human drama.

Transmission, Research, and Creation

Regarding transmission, what we can understand and transmit of a musical culture, and how to cultivate memory within the creative process:

interprétation de la Gwerz de Skolvan livrée sur le disque de Kristenn Nogués.

I also return to this question when explaining my interpretation of the Gwerz de Skolvan on Kristenn Nogués's album.

Comparative Listening

Pour aller plus loin, nous proposons l'écoute et l'étude d'une oeuvre en miroir : La gwerz de Sulian interprétée par Madame Françoise Loison, née Delaure.

To delve deeper, we propose listening to and studying a parallel work: La gwerz de Sulian, performed by Madame Françoise Loison, née Delaure.

The recording was made by Yann-Fañch Kemener in Corlay on July 24, 1978. This performance will be compared to another interpretation, the one I conducted with the Mallakastër Ensemble (2001).