France

Lo curat de la chapela

-

Genre :Dance music

-

Tradition :Massif central

-

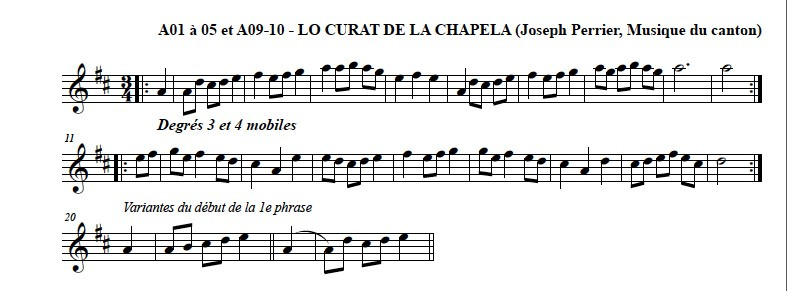

Piece name:Lo curat de la chapela

-

Specifics:Bourrée in triple time, instrumental dance tune

Lo curat de la chapela, "The priest of the chapel", bourrée played in three-time on violin by Joseph Perrier.

Recorded in Pérol, town of Champs-sur-Tarentaine, Cantal, circa 1986, by Eric Cousteix.

Originally published in the audio cassette «Musique du canton – Champs-sur-Tarentaine» (AMTA 1987), then put online on the Base Interrégionale du Patrimoine oral. Recording reproduced courtesy of Eric Cousteix

This highly developed bourrée is the culmination of a vast repertoire of related bourrées. This study proposes to trace the path of melodic evolution of these three-time bourrées from the Massif central, from the simplest with the bourrée La calha, to the most developed, with Lo curat de la chapela.

Lo curat de la chapela

Introduction of Lo curat de la chapela

This bourrée is one of the most developed melodies in its style and, for this reason, it was nicknamed «La dentelle» (The Lace) by one of the young musicians friends of Joseph Perrier.

Joseph Perrier remembered only the beginning of the lyrics in Occitan:

Lo curat de la chapela

Fasiá dançar la 'Lisabet

« The priest of the chapel made Elisabeth dance »

Joseph Perrier, Lot curat de la chapela song. Eric Cousteix's recordings

I have never met these words elsewhere. In the case of a very local verse, as is often the case for bourrées, perhaps is it the place called «La Chapelle» (the chapel), on the town of Condat, about twenty kilometers from Champs-sur-Tarentaine?

Examination of the vast repertoire of Joseph Perrier reveals plenty of related bourrées' melodies. Although frequently declined in several more or less similar versions, they are nevertheless individualized: the sung verses allow the musician to differentiate them, even when they sound alike. For example, lyrics with a different number of verses induce characteristic rhythmic details that point to a version of the tune.

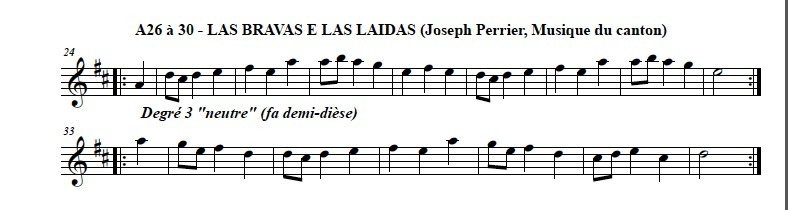

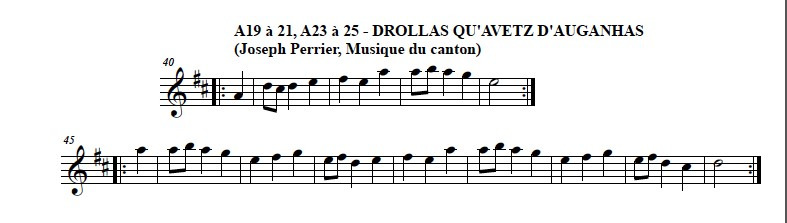

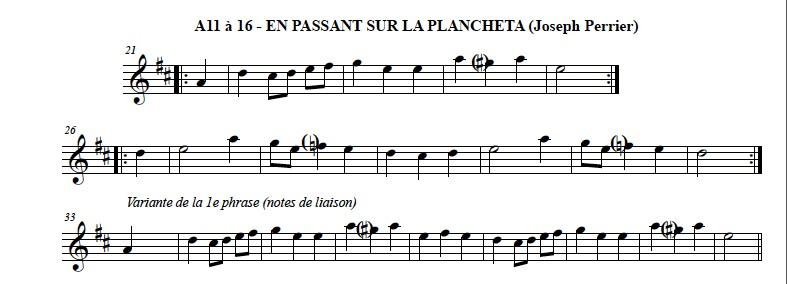

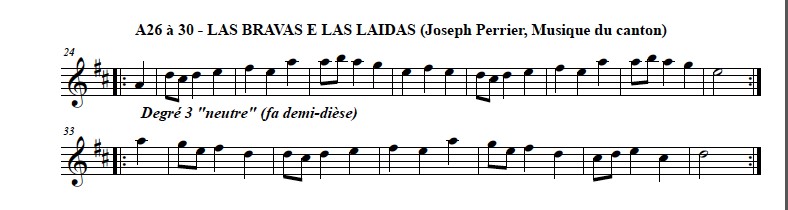

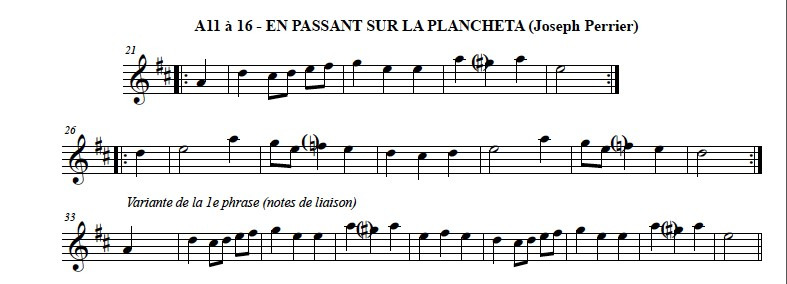

Thus, we can try to trace a melodic path of evolution from the simplest to the most developped, from « La calha » to « Lo curat de la chapela » including « Dròllas qu'avetz d'auganhas », « Chas la mair Antoèna », « En passant per la plancheta », « Las bravas e las laidas », all these tunes figuring in Perrier's repertoire and that we will listen to.

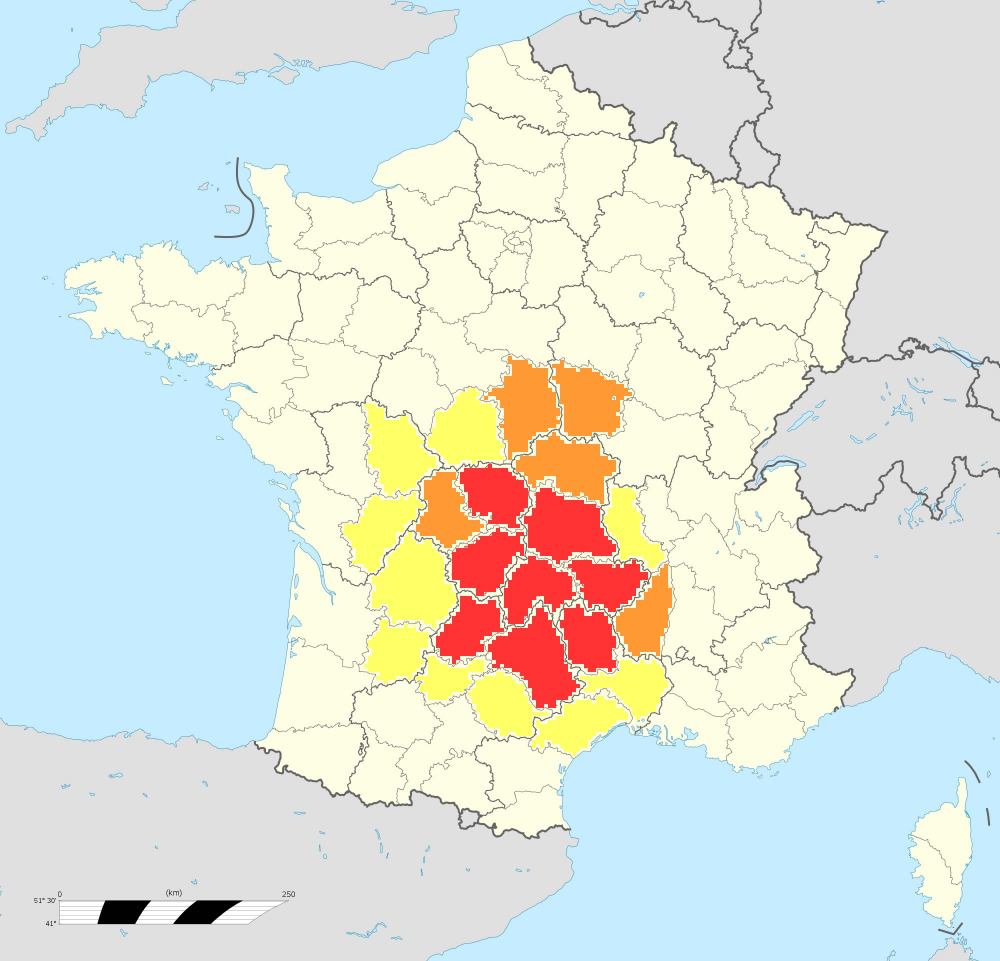

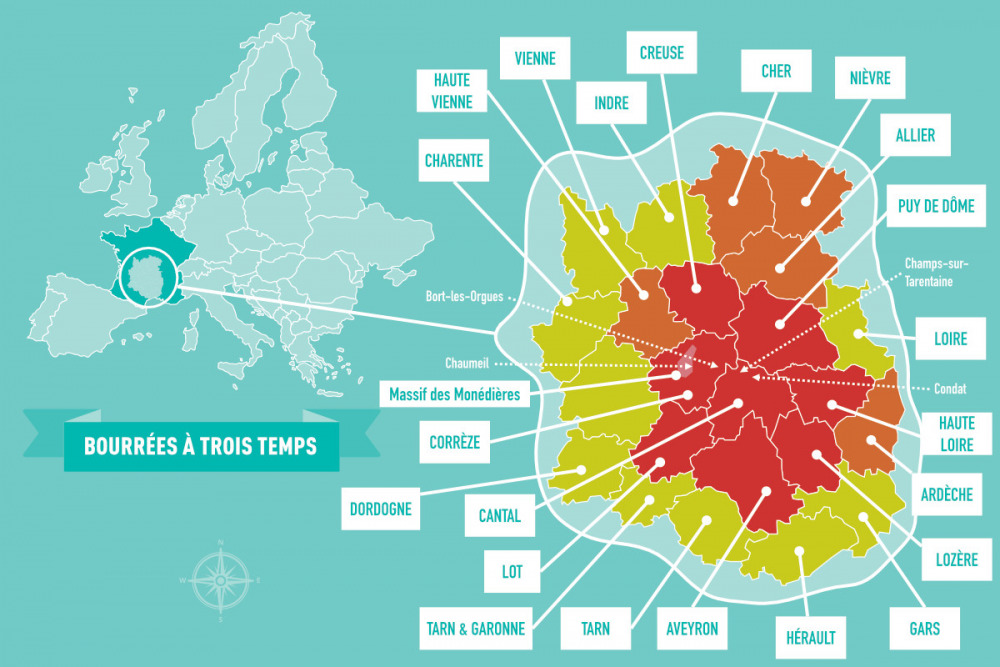

This broad repertoire is found in the region of the Massif central, considered in a very wide way. Here is the musical geography of these three-time bourrées in the Massif Central, schematically:

Three-tempo bourrées

Three-tempo bourrées

On these maps, I have indicated (very roughly) the departments in which traditional repertoire collections have shown three-time bourrées, as far as I know:

-

in red, when these bourrées are a fundamental element of the repertoire,

-

in orange, when they are more secondary, or present especially in a part of the territory,

-

in yellow, when it is a more sporadic or anecdotal presence.

Melodies evolution

Study of a family of melodies all related to each other, diversified from a simple archetype

As we deepen knowledge of three-time bourrées' repertoire, it is clear that most of the tunes are found in multiple variations. We are also led to make connections between related themes, although they are different in appearance.

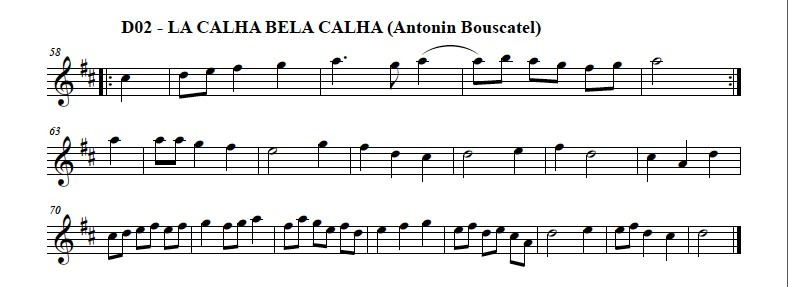

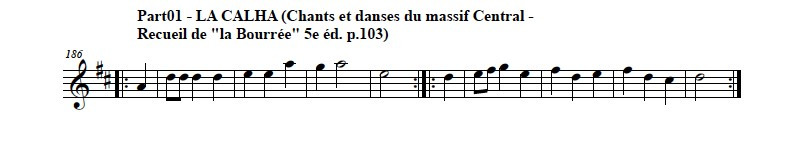

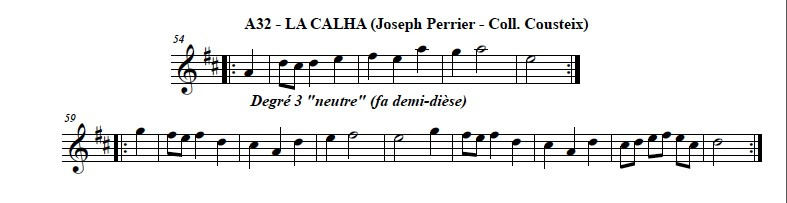

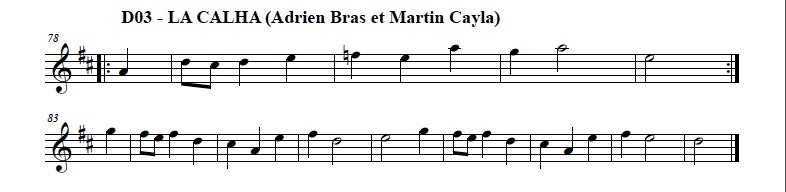

Thus, the two melodies of bourrées which are the subject of this work, Lo curat de la chapela and La calha ("The quail"), although very different, can both relate to a family of simpler bourrées, of which the well-known La calha could be the archetype.

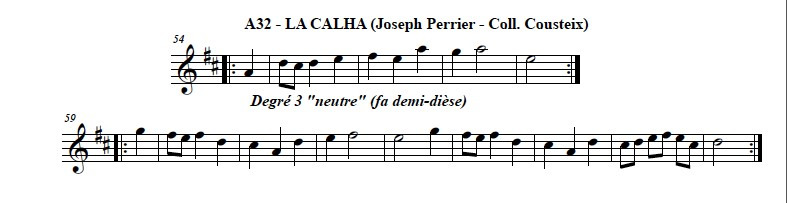

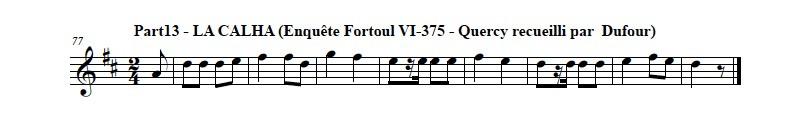

Here is the bourrée La calha in its interpretation by Joseph Perrier:

La calha, by Joseph Perrier. Recording courtesy of Eric Cousteix

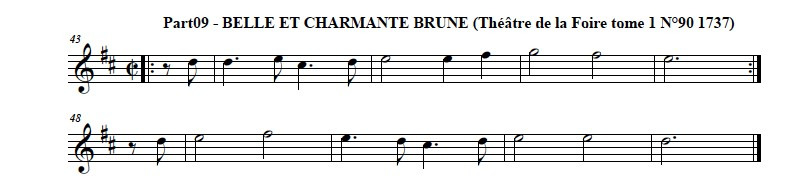

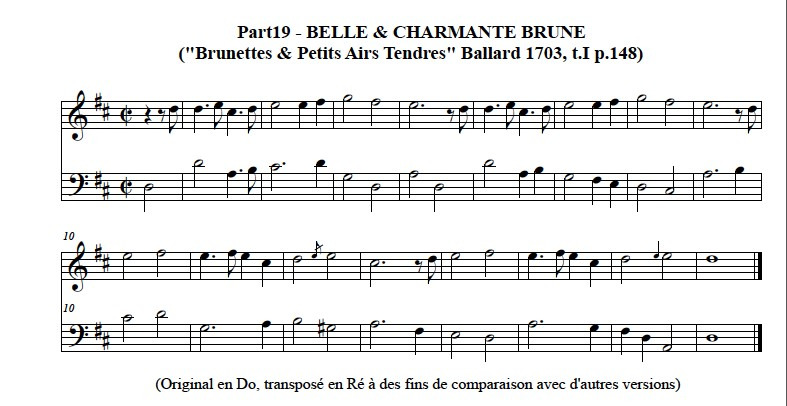

But we can still broaden the search, this melody, La calha, having itself two-tempo versions, of which we can find an obvious melodic antecedent in a song dating back to the seventeenth century.

Starting from this, it would be possible to trace a hypothetical evolutionary tree, whose different branches would lead to several distinct families of traditional songs.

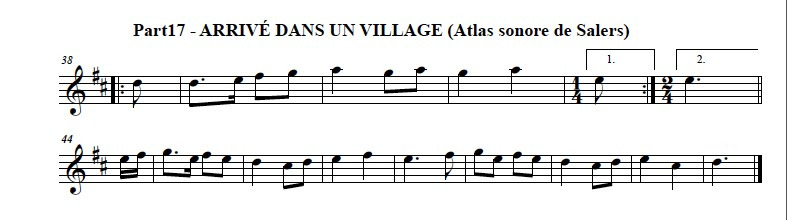

Some versions would play the role of «missing links», allowing to capture the similarities between the tunes, through their rhythmic, modal and melodic diversity.

This is what we will try to do, by discovering this repertoire of the three-tempo bourrées of the Massif Central.

Warning on transcripts

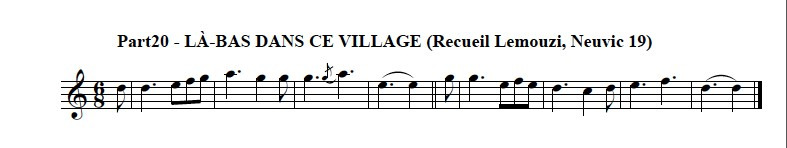

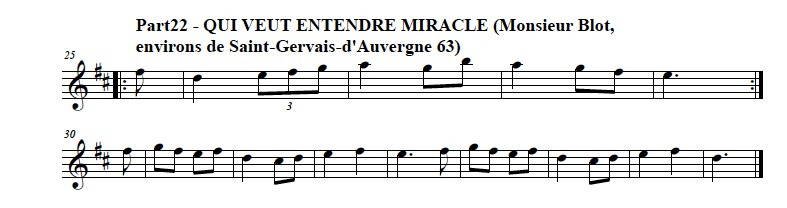

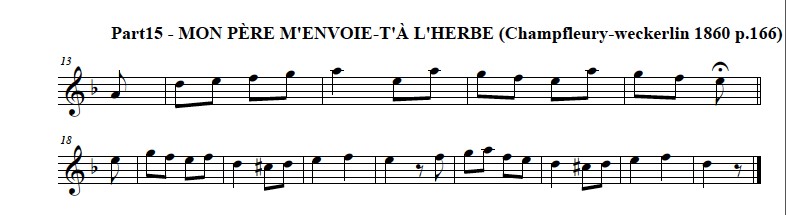

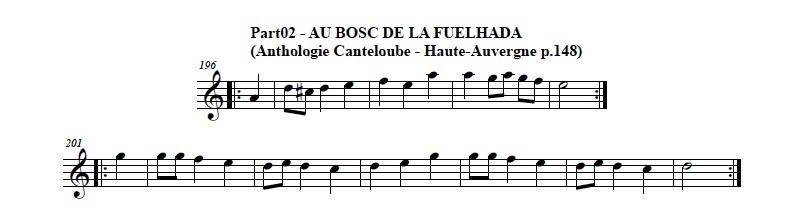

We give to listen in this work a large number of musical pieces accompanied by transcriptions. Where a piece could not be heard, it is as far as possible exposed through a transcript.

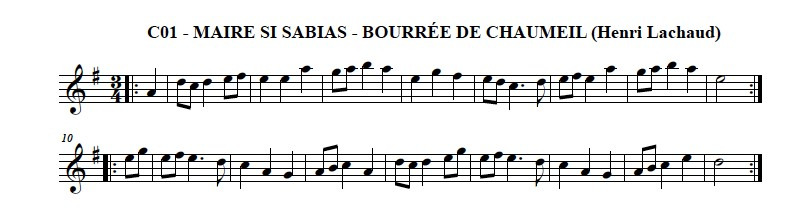

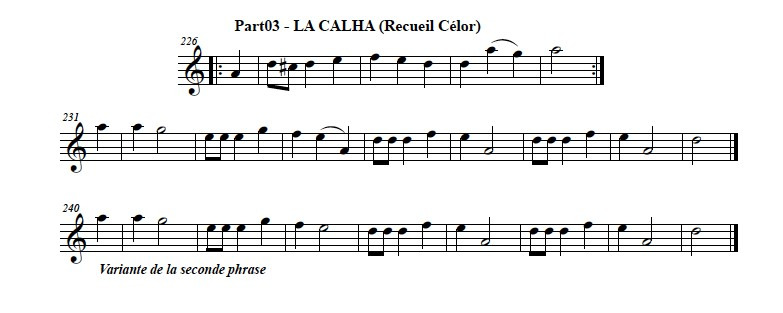

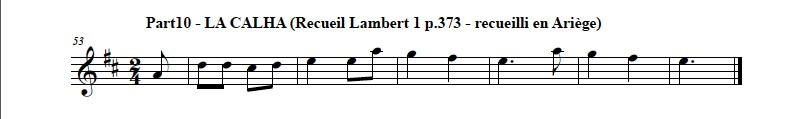

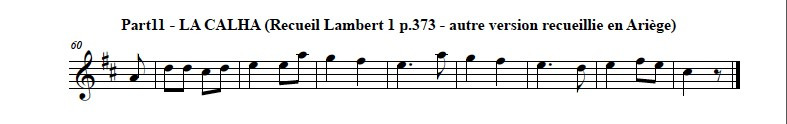

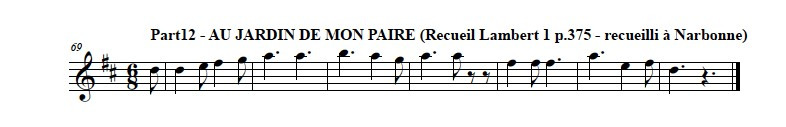

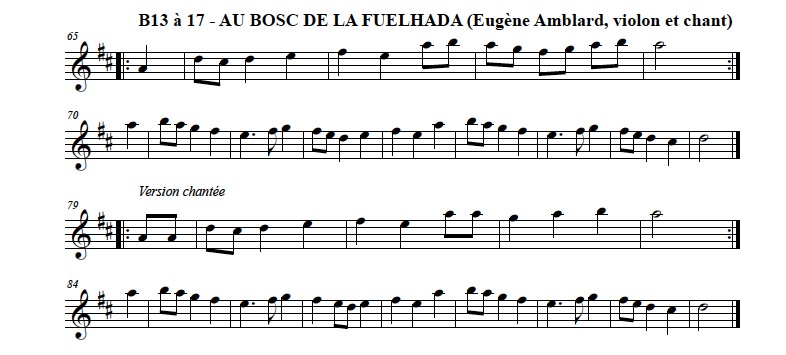

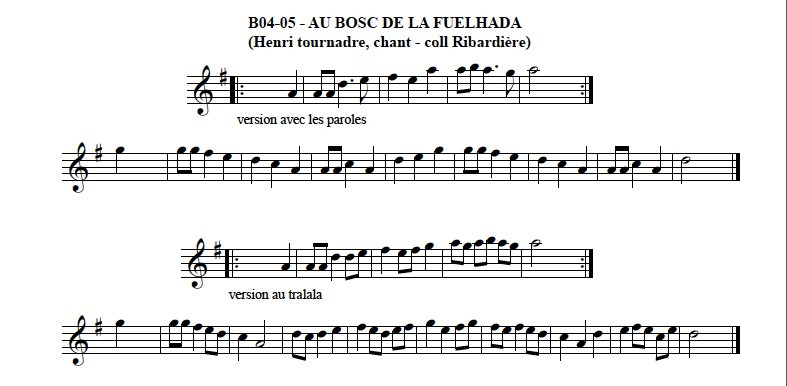

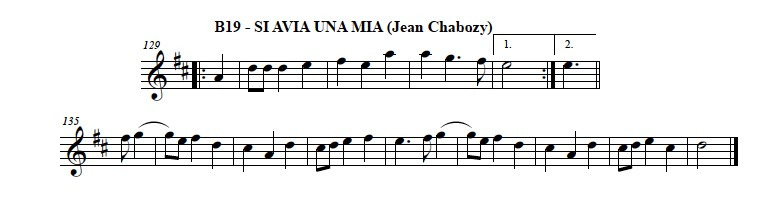

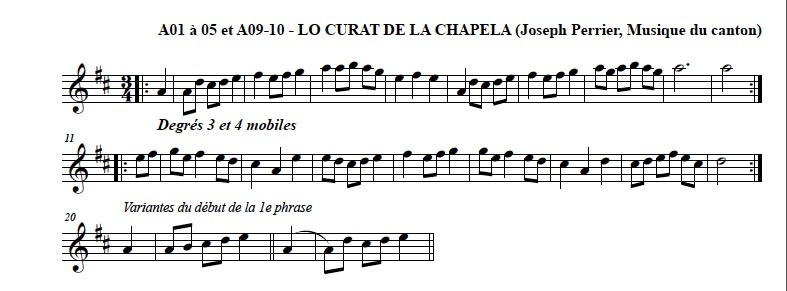

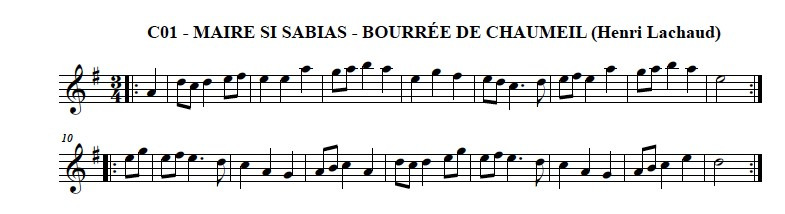

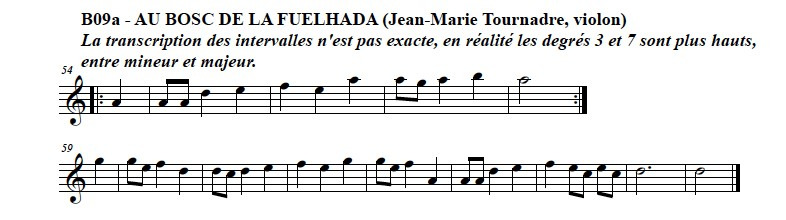

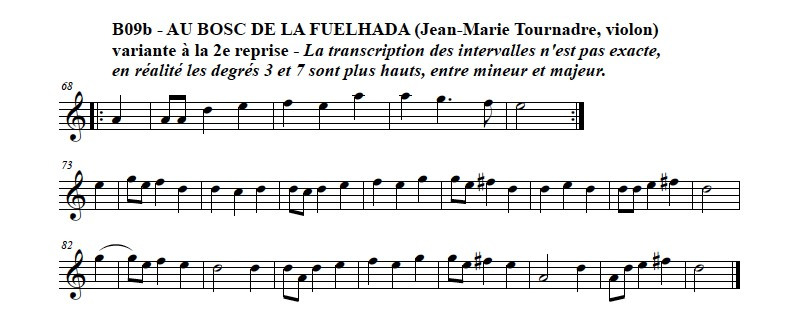

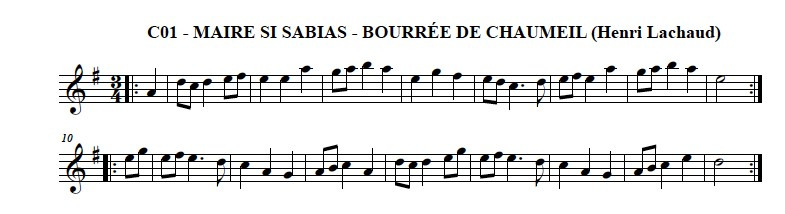

This series of transcriptions aims to bring together numerous melodies, sometimes very different, but that can be linked to the same «family tree». Whatever their original tone, all the melodies here have been transcribed and transposed in D key, to be more easily compared.

In the case of melodies transcription from sound recordings, We only focused on noting a main melodic line, leaving aside the ornamentation. Some melodic variations were taken into account, but not exhaustively, and the micro-intervals were not detailed either. As most sound sources are audible, we have to refer to them to understand the reality of the interpretations.