Syrie

Glorification of the Sublime : opening

-

Genre :Sacred music

-

Tradition :Aleppo Zikr

-

Piece name:Glorification du Sublime : ouverture

-

Specifics:Zikr

Zikr Qâdirî Khâlwatî of the Zâwiya Hilaliya in Aleppo

Singers:

Muhammad Hakim (lead singer), Abdullah Rihawi, Abdurahman Halak, Ahmad Machal, Muhannad Alwan, Ahmad Moslemani, Bakri Basal, Abdulhadi Kasara, Omar Shaban Hosayn, Ibrahim Karman.

This analysis offers commentary on an excerpt from a zikr (or dhikr) ceremony conducted by the Hilaliya Sufi order in Aleppo. The modal, melodic, and rhythmic structure is supported by a particular management of speed and intensity.

CD: Sufi Chant from Syria. Dhikr Qâdirî Khâlwatî of the Zâwiya Hilaliya, Aleppo, Unreleased/Maison des Cultures du Monde, 2002 (track 1). Recorded on March 22, 2001 at the Maison des Cultures du Monde (Alliance Française Theatre), Paris. © Maison des Cultures du Monde

The Zikr of the Hilaliya Zawiya

Zikr consists of the repetition of the name of God (Allah) and other names describing the divine, such as the Living and the Immutable, or other religious formulas. Zikr (from the root zakara) means "to pronounce" or "to remember the name of God." The term zikr also refers more broadly to the ritual ceremony during which a Sufi brotherhood gathers for this practice. A session includes various moments of chanting, recitation, and repetition of zikr formulas.

The brotherhood presented here is the Hilaliya Zawiya. The term zawiya can be translated as "brotherhood" and refers to all the people who participate in it. But it originally referred to the place associated with this brotherhood, reserved for prayer, meditation, and the ceremonies of dhikr. Literally, zâwiya means "corner; a place where one shuts oneself in." The Hilaliya Zawiya is considered the oldest of the zawiyas in Aleppo.

This dhikr ceremony has been held every Friday afternoon in the Hilaliya brotherhood's zawiya for 500 years, without interruption, even during wartime.

Composed of regular practitioners, the ceremony is open to all and can gather up to four hundred people, all of whom participate in the chanting. All participants are both performers and spectators. There is no stage.

The ceremony brings together people of all ranks within the brotherhood as well as the most humble members of the public. It can last up to 8 hours, but at least 3 hours in summer. It is composed of 8 parts (fasil) in summer and 5 to 7 parts in winter. It generally begins around 3 p.m. and lasts until sunset.

The ceremony, by Fawaz Baker. © Drom, 2020

Within the zawiya grounds, filming and recording are forbidden: this prohibition is imposed by the sheikh, that is, the leader and spiritual master of the brotherhood. This recording was made on the concert stage of the Maison des Cultures du Monde in Paris. It is therefore not a true zikr ceremony but rather its reenactment for a concert.

Ritual zikr and concert on stage, by Fawaz Baker. © Drom, 2020

The arrangement of the different parts of the fasl, the changes in rhythm and speed, the progression of the zikr... all depend on various parameters. Their study and transmission, presented here, was initially undertaken for a compositional project by Fawaz Baker Fawaz Baker :

From the practice of zikr to its study for a creative work, by Fawaz Baker. © Drom, 2020

The Poems of the Zikr

The sheikh did not wish to lead a zikr outside the confines of his Aleppo zawiya. However, for the concert from which this recording is taken, the lead cantor, Muhammad Hakim, conceived the concert's structure, generally respecting the order of development of a zikr, while also inserting pieces that would not normally fit within a zikr (for example, track 2 on the disc).

No instruments are used during the ceremony except on the 6th of summer. A duff, a frame drum, is then used. This section is called the sawi (literally: "piercing cry"). It is the climax of the ceremony. In other Sufi orders, up to 15 instruments may be used during the zikr, including the tebl or tabl (a double-headed drum).

The lyrics consist of poems accumulated through a tradition passed down orally to this day. Within the order's community, poets can submit poems, enriching the repertoire. More broadly, anyone can submit a composition or poems to the sheikh. Thus, the repertoire is not fixed: it continually incorporates new poems and melodies.

For each zikr session, the chants are suggested by the raïs (or rayes): the leader of the ceremony and also the principal soloist who performs the improvisations (here, Muhammad Hakim). However, the choice of chants performed also depends on the seasons and the religious calendar.

Glorification of the Sublime (Opening of the Zikr)

The piece analyzed here is the first, the one that opens the zikr. It accompanies the establishment of the religious framework of the ceremony. It begins with a litany on the Muslim profession of faith, the shahada: "There is no god but God." This is followed by praises to God, the Prophet Muhammad, and the founders of Sufi orders.

The translation in french of the text presented here is that of Hiyam Hamoui, which appears in the CD liner notes (details regarding the saints mentioned in the poem can be found in the "context" section of this study).

Sache qu’il n’y a de dieu que Dieu.

Ô Toi Celui qui ouvre, Toi l’Omniscient, nous implorons ton secours.

Ô messager de Dieu, nous avons confiance en toi.

Ô messager de Dieu, intercède en notre faveur.

Par Dieu, toi le médiateur dont les prières ne peuvent être qu’exaucées

Ô maître des lumières,

Ô toi qui brandis l’étendard sacré,

L’élu auquel s’adresse le Tout-Puissant,

Tu es piété et générosité.

Sans toi, ô le plus digne, le voyageur ne prendrait pas la route.

Être suprême, Donateur gracieux vers qui nous tendons,

Bienfaiteur adoré de l’univers,

Le Sublime vers qui montent les louanges.

Et toi, l’insouciant qui néglige son Seigneur, proclame : « Il n’y a de dieu que Dieu ».

Les Jîlâni m’apportent le réconfort

Dans la misère et l’affliction.

Pars et vagabonde, grise-toi d’amour,

Et contemple le pouvoir et la gloire du Sublime.

Ô colombes, des dunes stériles à la verte vallée de Aqiq,

Vos roucoulements se changent en lamentations.

Êtes-vous comme moi abandonnées par l’ami sincère ?

Donnez libre cours à votre ramage et chantez,

Ô Seigneur.

Saluez de ma part la maîtresse qui, sur le chameau, trône dans son palanquin.

Seigneur,

Au secours, ô messager de Dieu,

Au secours, bien-aimé de Dieu,

Au secours, toi qui es la porte de Dieu,

Au secours, seigneur, père de Yahya,

Au secours, seigneur Yahya,

Ô vous, de la maison du prophète, le messager de Dieu, au secours !

Ô compagnons du messager de Dieu, au secours !

Sidi ‘Abd al-Qâdir al-Jîlâni, Sidi Ahmad al-Rifâ’i, Sidi Ahmad al-Badawi, protégez-nous !

Sidi shaykh Ibrahim al-Desuqi, protégez-nous !

Sidi Saad al-Din al-Jibawi, protégez-nous !

Vous tous, amis de Dieu, protégez-nous !

Vous tous dont la présence et la protection nous comblent, protégez-nous ! Ô Seigneur.

Lorsque, pendant l’assemblée, l’échanson me donna à boire, je me réjouis.

Il n’était autre que le protecteur des Jîlâni,

Nous n’avions donc rien à redouter.

Ô toi ‘Abd al-Qâdir, le faucon magnifique qui nous vient en aide,

Ô toi, océan de bienfaits, sauve-nous, seigneur,

De la détresse en ces temps difficiles.

Petit frère, petit frère, accours vers la chaleur de la boisson,

Rends-moi visite, verse-moi encore de ton vin, car je ne vis plus.

Mon amour, ô seigneur,

Sois bienveillant et généreux, toi qui resplendit comme la pleine lune.

Ô seigneur, porte ton regard sur moi,

Pour l’amour de celui qui es la meilleure des créatures.

Ô seigneur, prie l’Omniprésent, pour le prophète de la Mecque dans sa pureté,

Pour sa famille, ses compagnons vertueux et Sidi ‘Abd al-Qâdir.

Zikr: Mastering Speed and Form

Modality and Tonality

Modality is the raw material of chanting, in that it is based on modes and not notes. Thus, we begin with a horizontal, not a vertical, chord, and the mode is not the octave. In other words, the musical language of modality, used here, is symbolic and not alphabetic (as in the case of tonal music). This corresponds more broadly to the conception and practice of narrative in Islamic culture.

Generally speaking, one could say that what is modal is chanting, and that from the moment an instrument is introduced, we already enter the tonal realm, a vertical dimension. But there is no strict boundary between tonality and modality, and all music borrows from both the worlds of modality and tonality, one or the other being more or less degraded.

This is why there is no fixed explanation for the relationship between tonality and modality. Tonality, in my view, evokes technology par excellence, something very metallic, something that cuts, that slices, like a razor blade. Modality, on the other hand, is organic, a living organism that ferments, bubbles, and develops. Between these two extremes, from one to the other, all possibilities exist.

Zikr, or the mastery of speed and form

The raïs (leader, principal singer) must control the three basic parameters:L

- speed

- tonality

- intensity

The three parameters are controlled separately. To do this, the notion of balance, in relation to one's worldview, is very important. Thus, these three parameters must never operate in the same direction. There are always one or two parameters that counteract the others.

This is what makes this type of interpretation unique, unlike widespread practices around the world where the higher the pitch, the faster and louder the singing. Here, one can sing softly but loudly.

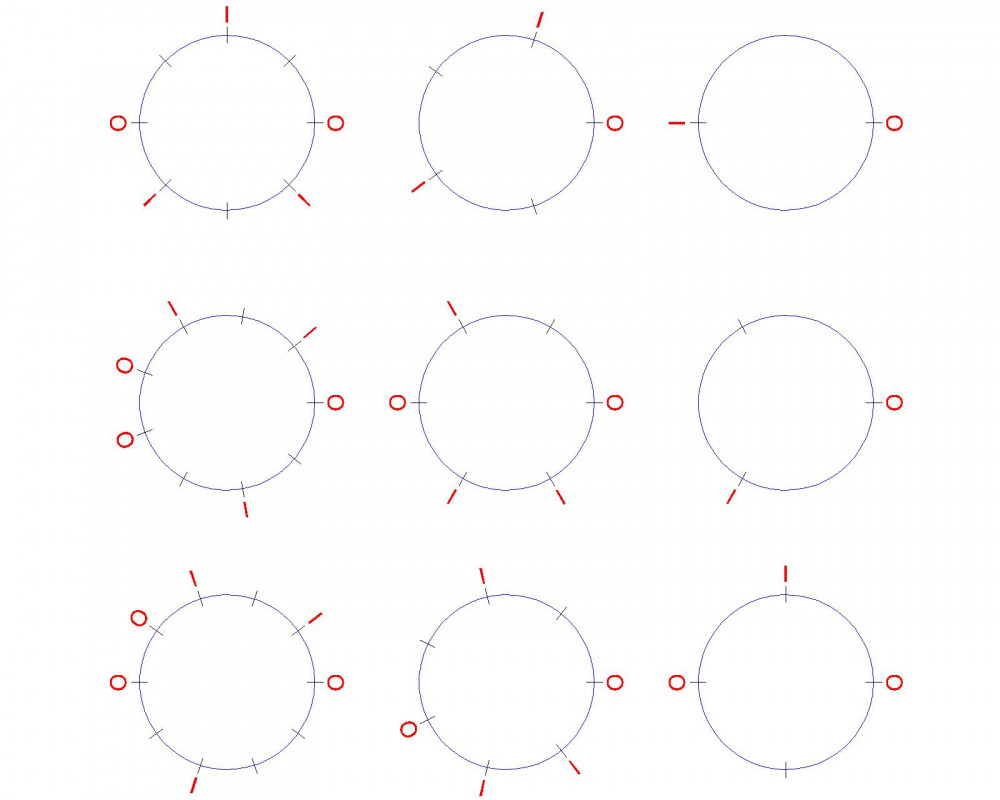

The aim is to separate the senses, resulting in nine possible interpretations depending on how these three parameters are balanced.

.

Speed, tonality, intensity in the zikr, by Fawaz Baker. © Drom, 2020

The other parameters that the leader must control are:

- the lyrics

- the melody

- body movements

- the interpretation

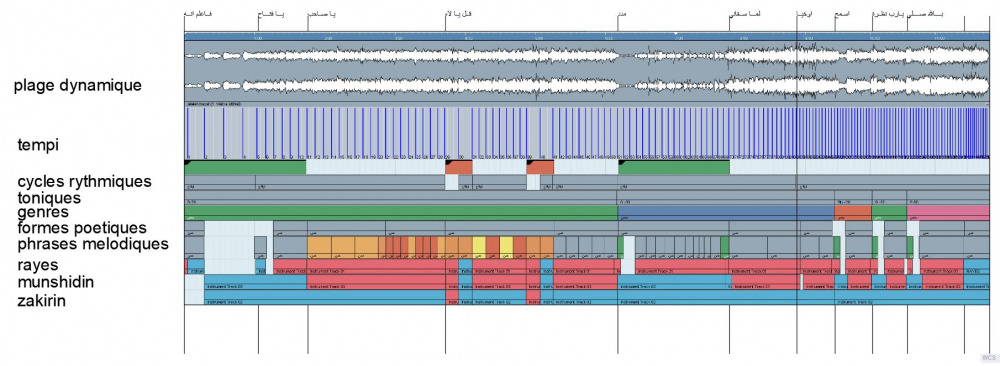

The simultaneous arrangement of these different parameters can be read and analyzed on this diagram of numerical analysis and graphic representation of the musical progression of the zikr, which I designed and wish to comment on:

(View enlarged and zoom in to see the details)

Analysis of the Progression of the Zikr

Commentary on the numerical analysis diagram, by Fawaz Baker. © Drom, 2020

Melodic Path and Modality

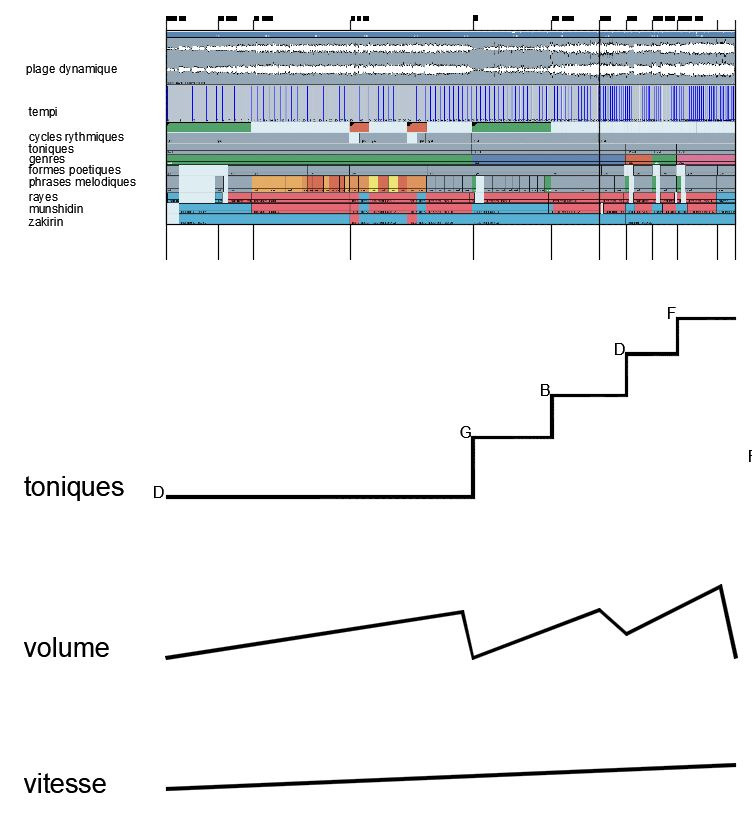

The leader begins his chant in the key of D, at the lower octave. The volume is low. The congregation joins in this same initial low key.

The chant then progresses to the third: B-flat then G.

The leader then performs a chromatic progression: throughout the ceremony, he changes tonic six times (C D E F# Ab B-flat C) and reaches the octave at the end of the excerpt.

This ascent is called taraqeh. While ascending, the master lowers the volume of the chant and changes its tempo. The tempo is halved, and the tonic is also halved.

The diagram below shows the parallel evolution of these different musical parameters:

Progression of the zikr

The leader thus initiates the assembly, and as soon as it is in tune, he begins his improvisation.

Each rhythmic cycle is composed of a formula, or phrase, which is repeated: it maintains the rhythm of each section. The measurement of time is based on a relationship between the ear and the eye, hearing and sight.

Each moment of the ritual corresponds to a mode, the different moments being called qismeh ("division, portion"). Melodic borrowings from the contemporary repertoire are possible if the melody is deemed "beautiful"; the lyrics are then added according to the texts proposed by the leader and the community.

The raïs, through his singing, assumes the role of transmitter of music and poems.

But the essence of the ritual is also to constitute a moment of collective invention, which is achieved in particular through the specific management of speed and intensity.

Speed and Tempo Progression

The raïs sets the tempo. The leader of the circle (halqah: circle, ring), who stands behind the raïs, maintains the tempo by tapping the back of his fist. The speed is never constant; it is dynamic. It is often ascending and descending, but much more rarely syncopated. The movements of tempo and speed are most often gradual, without breaks.

Generally, when the speed increases, it is customary to increase the volume. However, the opposite effect is sought in the interpretation of this ritual. The tempo starts at 33 bpm: this starting point corresponds to half the heart rate of the leader (estimated at around 66). The speed then increases to 56 bpm. This gradual increase in speed will lead, at the end of the excerpt, to a tempo of 132 bpm. This progression is achieved intuitively.

The concept of intensity and volume: dhikr, unlike interpretation.

The concept of intensity and volume: dhikr, unlike interpretation.

The greater one is, the more modest one must be. A cypress tree, the taller it is, the more it bows its head. When one is great, the more modest one must be. Thus, when increasing the speed, one does not raise the volume in order to avoid inciting applause. One must not be in interpretation, but in meditation. Humility is part of this notion of the sacred.

To put it another way, in the space-time of dhikr: the important thing is to ask questions, not to provide answers. This is not a stage where a singer can act like a star: it's impossible to stand tall like one – one is more like a cypress tree. In zikr, the more a singer knows, the more they contribute – unlike in a stage setting where the more a musician knows, the more they put themselves forward. Here, what matters is responsibility, not self-interest, and the frustration of performing doesn't exist because it's not about interpretation.

Rhythm Management

The concept of rhythm is expressed by the term lafuz: rhythmic cycle, which refers to pronunciation and prosody. But the rhythm during zikr is also guided by the body.

The movements of the participants during the ceremony accompany the music. Thus, the chant draws on this bodily energy to mark the beat.

Three rhythms are taken into account: the heartbeat, the breath, and movement (walking).

Rhythm, Cycle, and Time in Zikr, by Fawaz Baker. © Drom, 2020

For each fasil, the movement changes according to the rhythm. This results in the presence of a continuous polyrhythm.

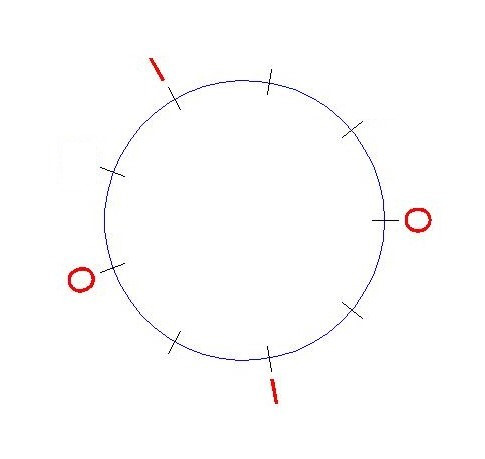

The rhythm is broken down into cycles of 9 beats, which can be simplified as much as possible to make them accessible.

There is an alternation between strong beats, weak beats, and rests:

- Dum : strong beat, represented here by ꓳ

- Es : rest (no symbol)

- Tak : weak beat, represented by ─

For example, for a rhythmic cycle of 9 beats:

Other rhythmic cycle configurations can also be represented in the same way for other musical styles:

Poetry, Rhythm, and Chanting in Zikrr

Another level of complexity arises from the fact that poetry is inherent to the rhythm. It thus influences this division of time.

Poetry, rhythm, and song, by Fawaz Baker. © Drom, 2020

In the practice of dhikr, in a sacred context, the complex rhythmic cycles of secular music are reduced to binary or ternary rhythms. Indeed, in the context of dhikr, it is necessary to control the speed and pitch (and other parameters) that determine the ritual, which requires rhythmic simplicity.

Similarly, the practice of maqâmsin dhikr is not about the complexity of modes. Nor is it about striving for virtuoso performance, which would be unmanageable with 500 singers (when the number of participants in the zikr is high). However, skill remains one of the fundamental criteria of the chant.

The aim of this practice is to reach the essence: virtuosity and talent lie in the control of a collective practice that strives toward this essence.

Organization of the Zawiya and Zikr: Space, Participants, and Transmission

Context: The organization of the social and musical space of zikr

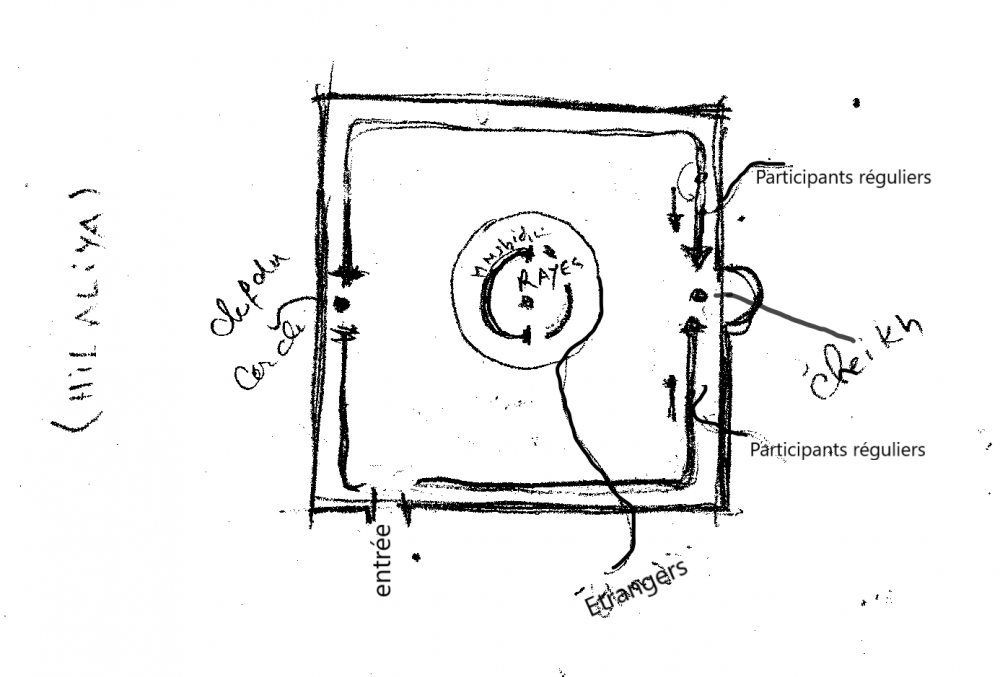

Spatial organization is very important in the ritual ceremony: it takes into account the direction of Mecca (the Qibla). This assembly is organized in a concentric circle.

Each place in the assembly is defined and hierarchical. This order is only modified if one of the members is absent (and will take their place upon their return).

The arrangement of the Zawiya Hilaliya assembly:

The different participants are positioned as follows:

- In the center stands the leader: the rais (or rayes).

- Around the rais are his two wings: the munchidin.

- Forming the assembly: the zakrin.

- The remaining audience: all the other participants.

- The sheikh of the zawiya stands on the opposite side from the head of the circle and the raïs. He is the owner of the premises. He represents the highest authority, the one who arranges the assembly and therefore seats all the participants. He is the first person one greets upon entering.

Members of the assembly assess each other based on their position. The closer they stand to the raïs, the higher their level of prestige. If necessary, the "people of God"—that is, those in whom the sheikh recognizes a proven commitment and a particular emotional strength—will be placed near the center, near the raïs. Outsiders will come next, due to the social prestige accorded to them. Regular attendees, who frequent the zawiya, are seated near the sheikh.

In the zikr, the participants' relationships with the sheikh and the raïs are quite different: one observes the sheikh (visual relationship) and listens to the raïs (auditory relationship).

Musical functions of the three groups of protagonists:

1. The leader: the raïs. He is the conductor, the conductor, and the principal soloist who performs the improvisations.

2. The wings: the munchidin, two principal singers who form the two wings around the raïs. These two wings can themselves have additional wings (up to 8 singers): they are hierarchically organized. These singers may later become raïs.

Their role is to maintain the melody of the chants, the lyrics, and the key (the latter determines the criteria for evaluating the singers' interpretation). They provide vocal support for the raïs and can improvise if the raïs gives them permission.

In this recording, the group of singers consists solely of the raïs and his munchidin.

3. Zakrin: the assembly. Their role is to maintain the pitch and rhythm. They repeat the rhythmic patterns and reprise the melody. The zakrin assembly can include up to 400 people. The one who leads the assembly is the leader of the circle, the halqah. He is positioned behind, on the other side, and sets the rhythm.

The singing of the ensemble evokes an emotion that brings tears to the eyes of the listeners, that is, the rest of the participants (the audience).

It is rare, however, for the audience not to sing at all: zikr is not a spectacle or a ceremony to be listened to, but rather to be practiced. The aim is to cultivate a strong sense of connection with God, rather than to induce a trance (which is inappropriate for this setting).

A Question of Learning and Transmission: Transmission, Memory, Creation

The Accuracy of Modes and the Transmission of Knowledge: Remembering the Masters

Those who perform the modes have acquired a high degree of accuracy through the transmission of knowledge from master to student, via repetition.

But it is far from being solely a matter of musical knowledge: the skill of singing—that is, the ability to sing the modes correctly—is linked to memory and the remembrance of past and deceased masters.

This remembrance is the foundation for constructing the interpretation, the condition for the emotional intensity necessary for the functioning of zikr.

If the criterion for judging singers is indeed the accuracy of their intonation and the modes they sing, this knowledge primarily refers to the modes transmitted by the masters—that is, with their weight of memory—before potentially also encompassing an intellectual understanding of the maqâm and its theory. This intellectual knowledge is not essential, whereas the knowledge acquired through transmission and thus through heartfelt practice is necessary.

Outside of the zikr ceremony, some singers are tasked with transmitting this knowledge to future generations. In this case, today, they use recording devices such as mobile phones and smartphones.

Singing and Memory Remembrance, by Fawaz Baker. © Drom, 2020

Other concert recordings

I myself have sung zikr pieces in concert with the Nawa Band... although zikr cannot be performed in concert.

A few notes before a video excerpt from these concerts:

Work and concerts with the Nawa Band, by Fawaz Baker. © Drom, 2020

The Nawa Band in concert in Aleppo, 2009. © Nawa Band / Fawaz Baker

Other recordings of a Nawa Band concert at the Damascus Opera House can be seen here:

The Maqam in Practice: Modes, Jins, Modulation

A Concentration of Arabic Music and the Making of a Maqâm

A maqam is a succession and progression of genres called jins (plural ajnas).

A maqam can contain 15 genres.

A jins ("genre") can be defined as a horizontal chord composed of 3, 4, or 5 notes used in the music of the Middle East and Near East.

There are currently nine of these, which can be classified as kings, queens, princes, and princesses, and from these, families of genres can be formed. These 9 genres are as follows:

- 3 rois de 5 notes qui sont :

- Nahawand (1er roi, genre mineur) : do – ré – mib – fa – sol

- Rast (2ème roi) : do – ré – mi1/2b – fa – sol

- Nikriz (3ème roi, triton) : do – ré –mib – fa# – sol

- 4 reines de 4 notes :

- Kurdi : sol – lab – sib – do

- Hijâz : sol – lab – si – do

- Bayati : sol – la1/2b – sib – do

- Saba : sol – la1/2b – sib – si

- 1 princesse : Sigah : mi1/2b – fa – sol

- 1 prince : Ajam (majeur) : mib – fa – sol

All these genres follow one another to form maqams. They should be seen as a progression. They are horizontal chords that are placed end to end to compose.

Thus, kingdoms are formed: 1 king + 1 queen + princess and/or prince. The kingdom constitutes an octave from C to C, but is not necessarily 7 notes; it is a space of possible paths within the space of the kingdom determined by the genres combined.

However, starting from the same tonic: they can be combined, but they are then siblings, and the rules are therefore different from those of marriage between a king and a queen.

Fawaz Baker plays these genres, their succession, and their formation into kingdoms on the oud:

Genres (jins) and Modes (maqams), by Fawaz Baker. © Drom 2020

Modulation and Transposition

To modulate, starting from the fifth—which is the pivotal or dominant (or fixed) note—one enters another chord by combining the king and queen, for example, Rast in C and Bayati in G. To this, one can then add Bayati's sibling in G, that is, Rast in G.

Alternatively, one can combine the king and queen from any tonic, for example, Bayati and Nahawand in G.

The interplay then takes place between the processes of transposition and modulation, which are quite different.

To summarize, let's say that in Arabic music, a mode is the genre, the jins; whereas in Coltrane's music, the mode is the realm formed by the king and queen (Ionian, Dionysian modes, etc.).