Turquie

Segah Şarkı

-

Genre :Formal music

-

Tradition :Makam, Ottoman classical music

-

Piece name:Segah Şarkı

-

Specifics:

To listen to and understand the Ottoman makam, Serdar Pazarcıoğlu performs here the song (şarkı) "Dönülmez akşam ufkundayız vakit çok geç" ("At the edge of the irreversible evening, it is already late") in the Segah makam. This piece was composed by Münir Nurettin Selçuk, a singer and composer active on the Istanbul music scene from the 1920s onwards, to a poem by Yahya Kemal Beyatlı.

Recorded on octobre 2020, © Serdar Pazarcıoğlu

"Dönülmez akşam ufkundayız vakit çok geç" in the Segah makam by Serdar PazarcıoğluRecorded in October 2020, © Serdar Pazarcıoğlu.

Introduction to Ottoman maqam

In the Ottoman tradition, the term makam refers to the modal system used in classical music, as well as its various components. Without going into detail here, it's important to know that the term makam (ou maqâm) has other meanings in neighboring traditions.

The makam that developed in Istanbul is the result of the convergence of Turkish, Arabic, Persian, and Byzantine traditions. It possesses a whole vocabulary in Persian that describes a reality specific to this Ottoman culture, which must be distinguished from its Persian or Azerbaijani counterparts, although their historical origin is shared.

It should be noted, however, that within the Ottoman tradition itself, the same name, for example rast, can designate three different things (we will retain this threefold spelling throughout the analysis):

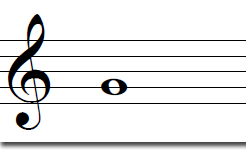

- the RAST degree:

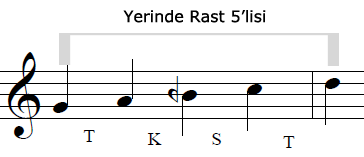

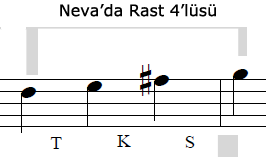

- the rast pentachord (NB: yerinde means that it is here in its "original," untransformed form):

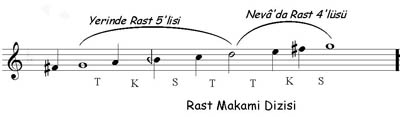

- The makam Rast :

Thus, RAST can be said to be the first degree of the first rast tetrachord that makes up the makam Rast.

The Degrees in Ottoman Makam

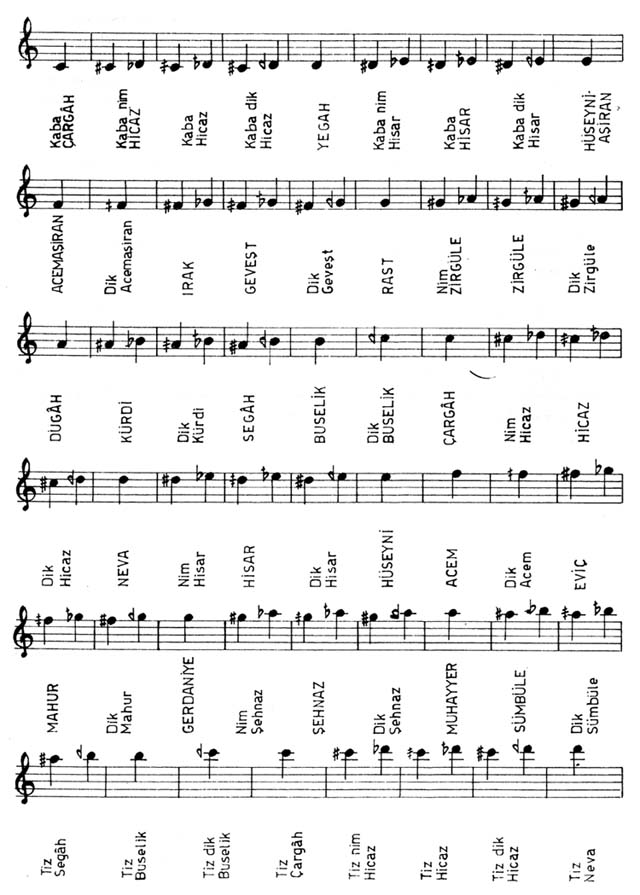

Here is a table summarizing the names of the degrees within the two octaves in which Turkish makam unfolds:

The degrees (perde, pl. perdele) in Ottoman makam

Transposition et notation des degrés et intervalles

In this study, we prefer to use traditional vocabulary because it allows for easy navigation within the musical space while avoiding problems related to transposition. Indeed, depending on the singers' vocal range, the entire system is transposable; thus, RAST remains RAST even a tone lower.

It seems necessary here to review the notation. Ottoman music has been written for a century using Western notation thanks to a set of additional symbols. The notes are most commonly named DO RE MI etc., except when there might be doubt about the nature of the note, in which case we immediately switch to their vernacular names.

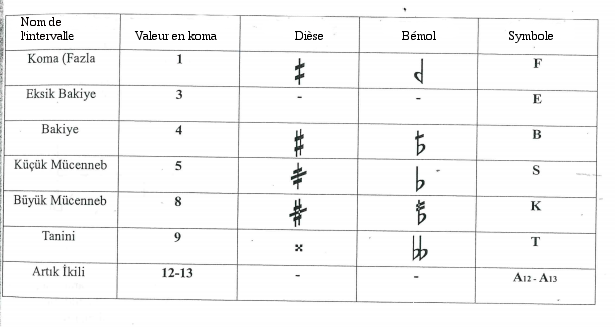

Intervals in the Ottoman Makam:

It should also be noted that the pitches do not necessarily coincide with the Western reference frame. Thus, the main transposition of instrumental music, the bolahenk, is transposed a fourth lower; therefore, RAST, written as SOL, is heard as RE (293.7 Hz).

Similarly, if transposed to süpürde (a whole tone lower), RAST will still be written as SOL but heard as DO (261.6 Hz).

How the Makam Works

The makam ("place" or "space" in Arabic) as a system is an open-ended collection of several makam (in the sense of modes). It becomes audible through movement within and between these different spaces.

These modes are characterized by their scale (dizi) but especially by their seyir, a melodic development specific to each. Thus, two makams of the same scale constitute two distinct makams if one begins its progression on the root and the other on the fourth.

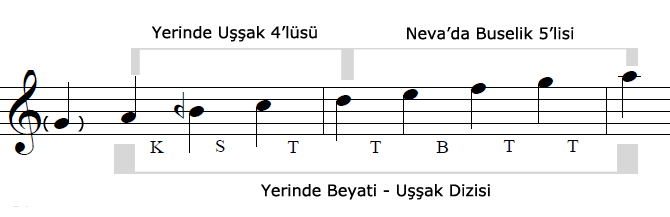

Let's take Uşşak and Beyati as examples:

The workings of the makam. Practical illustration on the Uşşak and Beyati scale by Ruben Tenenbaum (recorded in October 2020, © R. Tenenbaum)

Uşşak begins its progression around the root, then ascends to the fourth and descends again. It is said to be ascending.

While Beyati begins directly around the fourth and descends to the tonic. It is said to be ascending-descending.

These developmental zones are structured around polarized notes, which are also the point of junction of the trichords, tetrachords, or pentachords contained within the makam. Indeed, if we break down the Uşşak and Beyati scale, we find a tetrachord of uşşak and a pentachord of buselik, both structured around the fourth.

Thus, the scale of a makam can be understood as the sum of a tetrachord and a pentachord, which are themselves limited in number.

The theoretical description using tetrachords is the most widespread. It is quite functional, and all makams have been described in this way. However, this structure should not obscure the fact that within this framework, we find motifs that allow us to identify makams and more precise melodic patterns, which are less frequently verbalized.

Segah Şarkı - Dönülmez akşam ufkundayız vakit çok geç

In the title of this piece, Segah Şarkı Dönülmez akşam ufkundayız vakit çok geç, we find a first level of information that reveals the makam, in this case Segah, and the form, şarkı, which designates a song (or a lied).

Then comes the first verse of the poem, which distinguishes it from the hundreds of other Segah Şarkı.

The Segah makam

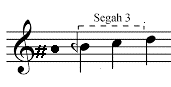

Segah is said to be ascending, because it begins its development on the root note and must rise to develop.

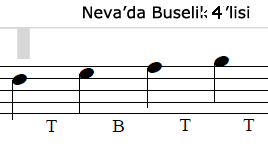

Its root (karar) is SEGAH and the subtonic (yeden) is KÜRDI. It is composed of the trichord of segah on the SEGAH degree and the tetrachord of rast, which alternates with the tetrachord of buselik on the NEVA degree:

The first phase of development revolves around the SEGAH degree, polarized between RAST and NEVA.

The polarisationthen shifts towards NEVA with the alternation between rast and buselik, before finally returning to SEGAH, which is reinforced from below with KÜRDI.

Makam Segah, explained in practice by Ruben Tenenbaum (recorded in October 2020, © R. Tenenbaum)

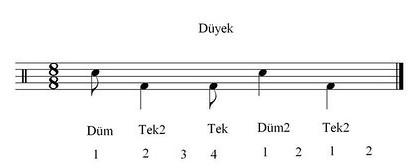

The usul (rhythmic cycle) used is Duyek:

Dönülmez akşam ufkundayız vakit çok geç :

This musical piece was composed by Münir Nurettin Selçuk, a singer and composer active on the Istanbul music scene from the 1920s onwards.

Münir Nurettin Selçuk in concert © DR

Münir Nurettin Selçuk in concert © DR

Besides his early, acclaimed recordings, Münir Nurettin Selçuk is known for his influence on Western classical music, particularly for introducing choirs into Turkish music (today, many choirs are still active throughout Turkey). He is also credited with the first solo concert, singing in tails in front of the orchestra, whereas traditionally the singer was part of the ensemble.

Here he composed on a poem by Yahya Kemal Beyatlı, the first verse of which gives the name to the musical piece:

Dönülmez akşamın ufkundayız vakit çok geç

Bu son fasıldır ey ömrüm nasıl geçersen geç

Cihâna bir daha gelmek hayâl edilse bile

Avunmak istemeyiz böyle bir teselliyle.

Geniş kanatları boşlukta simsiyah açılan

Ve arkasında güneş doğmayan büyük kapıdan

Geçince başlayacak bitmeyen sükûnlu gece.

Guruba karşı bu son bahçelerde keyfince

Ya aşk içinde harap ol ya şevk içinde gönül

Ya lale açmalıdır göğsümüzde yahut gül

Dönülmez akşamın ufkundayız vakit çok geç.

At the edge of the irreversible evening, it is already late

The music has fallen silent, oh my life, it is late

Even the dream of resurrection

Is ultimately a meager consolation.

In the unfathomable darkness opened by the gates

Of the sky where the sun no longer rises,

The night begins, silent, infinite.

To savor the last sunset,

Or to be consumed by love, to have a passionate heart,

Or for roses and tulips to bloom in our souls,

At the edge of the evening, with no return, it is already late.

Modal Analysis of Segah Şarkı - Dönülmez akşam ufkundayız vakit çok geç

We have a solo version by Serdar Pazarcıoğlu, and another for an ensemble where he is joined by Samet Pazarcıoğlu on clarinet, Sadullah Hepgüler on kanun, Erdal “Eco” Ercan on darbuka, and Serkan Aktaş on vocals. This version of the piece by Serdar Pazarcıoğlu and the ensemble was recorded in October 2020.

We offer a comparative modal analysis of these two versions, first the ensemble version and then the solo version, by breaking down their development.

Modal Analysis of the Ensemble Version

Aranağme - Introduction - Measures 1-6

A kind of condensed version of the Segah makam, measures 1-2 revolve around the Segah scale over a Rast-Neva range. The upper section is explored with a half cadence (yarım karar) on Neva in measure 4, followed by a descent to the tonic and a cadence (tam karar) on Segah.

Song - Phrase 1, mm. 7-11

Focusing solely on the Segah scale. The first section relates to Rast, followed by a stabilization of the cadence supported by the yeden (subtonic) Kürdi.

Song - Phrase 2, mm. 12-19

Focusing on the third, Neva. We observe the mobility of the fifth, which alternates between EVIC and ACEM (FA#/FA♮) to form the tetrachords rast and buselik respectively on NEVA.

Song - Phrase 3, mm. 20-23:

The instrumental response, Saz payı, recalls the first part of the aranağme, concluding on SEGAH and introducing a Segah motif on EVIC (in practice, we would say that we have modulated to Evic, even though the entire makam is not expressed). We enter the modulating section of the piece, called meyan.

Song - Phrase 4, mm. 24-27:

Segah on EVIC in the first two bars, then the introduction of SÜMBULE, which adds color without actually presenting an existing makam; this is the diminished tetrachord of segah (eksik dörtlü). Saz payı forms a half cadence on EVIC.

Song - Phrase 5, mm. 28-35:

From measure 28, emphasis on the GERDANIYE scale leading to the Mahur makam. The same pattern continues in the instrumental section up to measure 35, which ultimately concludes with a Segah motif (çeşni) on the octave (TIZ SEGAH).

Song - Phrase 6, mm. 36-43:

The music meanders in the Segah register in the upper register. Concludes on EVIC.

Song - Phrase 7, mm. 44-48:

Emphasis on GERDANIYE leading to Mahur (mm. 44). Introduction of the Hicaz tetrachord on NEVA (mm. 45), then Hicaz on GERDANIYE, reminiscent of the upper part of the Hicazkar makam:

Song - Phrase 8, mm. 49-55

The ACEM and KÜRDI appear, introducing Kürdilihicazkar, and the rhythm stops in measure 51.

Variation from the solo version in measure 53: in the solo, Serdar Pazarcıoğlu already introduces the EVIC degree, which will allow the return to Segah; whereas here, he arrives directly in the following measure with Segah.

Song - Phrase 9, measures 56-63

Landing phrase in Segah towards the conclusion. The singer makes a slight variation that leans towards Hüzzam in the first instance. Hüzzam is close to Segah, but it presents a tetrachord of hicaz on NEVA.

Song - Phrase 10

Repetition of the first verse and concluding section.

Scores

In addition, here are the published scores of this composition:

Modal analysis of the solo version:

Sequences of: Segah Şarkı Dönülmez akşam ufkundayız vakit çok geç - Serdar Pazarcıoğlu

Aranagme - Introduction - Measures 1-6

A kind of condensed version of the Segah makam, measures 1-2 revolve around the SEGAH degree over a RAST-NEVA range. Exploration of the upper part with a half cadence (yarım karar) on NEVA in measure 4, then a descent to the tonic and a cadence (tam karar) on SEGAH.

Phrase 1, Measures 7-11

Focus solely on the SEGAH degree. The first part relates to RAST, followed by a stabilization of the cadence with the support of the yeden (subtonic) KÜRDI.

Phrase 2, Measures 12-19

Polarization of the third, NEVA. The mobility of the fifth is observed, alternating between EVIC and ACEM (F#/F♮) to form the tetrachords rast and buselik respectively on NEVA.

Phrase 3, Measures 20-23

Saz payı (instrumental response) recalling the first part of the aranağme, which concludes on SEGAH and introduces a Segah motif on EVIC (in practice, we would say that we have modulated to Evic, although the entire makam is not expressed). We enter the modulating section of the piece, called meyan.

Phrase 4, Measures 24-27

Segah on EVIC in the first two measures, then the introduction of SÜMBULE, which adds color without actually presenting an existing makam; this is the diminished tetrachord of segah (eksik dörtlü). Saz payı plays a half cadence on EVIC.

Phrase 5, Measures 28-35

From measure 28 onward, emphasis is placed on the GERDANIYE degree towards the Mahur makam. The same pattern continues in the instrumental section until measure 35, which finally concludes with a Segah motif (çeşni) on the octave (TIZ SEGAH).

Phrase 6, Measures 36-43

The Segah meanders in the upper register. Concludes on EVIC.

Phrase 7, Measures 44-48

Emphasis on GERDANIYE towards Mahur (m. 44). Introduction of the hicaz tetrachord on NEVA (m. 45), then hicaz on GERDANIYE, reminiscent of the upper part of the Hicazkar makam:

Phrase 8, Measures 49-55

Appearance of ACEM and KÜRDI, which evoke Kürdilihicazkar, and a break in the rhythm at m. 51.

Variation from the solo version at m. 53: in the solo, Serdar Pazarcıoğlu already introduces the EVIC degree, which will allow the return to Segah; whereas here, he arrives directly in the following measure with Segah.

Phrase 9, Measures 56-63

Landing phrase in Segah towards the conclusion. The singer makes a slight variation that leans towards Hüzzam in the first instance. Hüzzam is close to Segah, but it features a tetrachord of hicaz on NEVA.

Phrase 10

Landing phrase in Segah towards the conclusion. The singer makes a slight variation that leans towards Hüzzam in the first instance. Hüzzam is close to Segah, but it features a tetrachord of hicaz on NEVA.

Segah Taksim by Serdar Pazarcıoğlu

(recorded in October 2020, © Serdar Pazarcıoğlu)

As a complement to the study of Segah Şarkı Dönülmez akşam ufk undayız vakit çok geç,

we propose studying a taksim(individual improvisation) in Segah by Serdar Pazarcıoğlu:

- Phrases in Segah over a fairly wide range, constantly returning to the Segah degree

- Phrases in Segah over a fairly wide range, constantly returning to the Segah degree

- Polarization of the third, Neva

- Emphasis on the rast tetrachord

- Alternation on the fifth between Evic and Acem

- Return to the root

- Opening on the Evic degree with a Segah motif. Then, support on GERDANIYE to form the rast tetrachord (on NEVA).

- The buselik tetrachord leads to a conclusion (3:38) which is developed as a kind of coda until 4:04.

- Support on the EVIC degree for a Segah motif on the octave. Modulation to Evcara on SEGAH (with ambiguity regarding the Hicazkar conclusion which lowers the fifth; Evcara is sometimes described as a transposition of Hicazkar), then a return to TIZ SEGAH.

- The emphasis on TIZ NEVA makes Evcara disappear; Segah phrases on the octave appear, but in the descending Evcara, there is a return and exposition of a Segah motif on TIZ HÜSEYNI, finally concluding with a Segah motif on TIZ SEGAH.

- Descent with the Gülizar makam, which is a descending form of the Hüseyni makam, the latter being more common.

- Flavor of Müstear

- Return to Segah and conclusion