Inde

Raga Nat bhairav

-

Genre :Formal music

-

Tradition :Raga, Khayal, Hindustani classical repertoire

-

Piece name:Raga Nat bhairav

-

Specifics:Rāga Naṭ bhairav, addha tāla

Tero gun bhed apār - Your qualities and your mystery are infinite

Artists: Sudhanshu Sharma (vocals), Saptak Sharma (tabla), Abhishek Sharma (harmonium), Manisha Ma Prem (tanpura)

Hindustani music is found in North India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and, to a lesser extent, in the Herat region of Afghanistan.

Overview of the Work

Khayāl chant in the rāga Naṭ bhairav by Sudhanshu Sharma, recorded in Delhi in October 2017 for this module.

Khayāl is the main vocal genre of Hindustani music.

"Tero gun bhed apār" [Your qualities and your mystery are infinite] is a devotional khayāl chant by an anonymous composer. It is presented within the sixteen-beat metric/rhythmic cycle (tāla) called addha tāla, which is a variation of the basic tīntāla cycle, in medium tempo.

Sthāyī: Tero gun bhed apār

tu nirādhār ke hī ādhār/

Antarā: Anāth ke nāth

dīn ke sāīn

dijo daras sākār//

Your qualities and your mystery are infinite.

You are the defender of the weak.

[You are] the protector of the neglected,

[You are] the God of the poor,

Please take form before us!

Rāga Naṭ bhairav

In Indian classical music, both in the North (Hindustani music) and the South (Carnatic music), modality is embodied by the notion of rāga.

Concept of Raga

Each raga is defined by an ascending (āroha) and descending (avaroha) scale, sometimes different, by dominant notes called vādī (speaking) and samvādī (co-speaking), by a hierarchy of note importance, as well as by characteristic movements (calan) and melodic phrases (pakaḍ). Each raga is also associated with a playing time (prahar) or a season, as well as a dominant feeling (rasa).

A raga is presented as a musical being endowed with its own personality and character.

Henri Tournier's presentation of the concept of rāga

"In Hindustani music, the tālā is a particular system of rhythmic cycles whose concept is very close to the metrics of poetry. The first beat of the rhythmic cycle is the sam. Each rhythmic cycle is characterized by a number of beats (mātrā), distributed in sections (vibhāg) that can be of unequal length."

Structure Overview

The musician begins with the ālāp, the unmeasured prelude that introduces the scale and movement of the rāga note by note.

The musician then develops the rāga using syllables from the text, the names of the notes (sargam), and improvised phrases at a fast tempo (known as tān).

- ālāp: unmeasured prelude introducing the scale and melodic movement of the rāga

- sthāyī: "first part of the composition centered around the middle tonic > 1’20: first part of the sthāyī > 1’46: second part of the sthāyī > 2’02: return to the first part of the sthāyī"

- antarā: second part of the composition centered around the high tonic and improvisation

- development: improvised development around the words of the lyric poem (of the sthāyī)

- mukhṛā: return to the first part of the verse

- development: improvised development around the words of the lyric poem (of the sthāyī)

- mukhṛā: return to the first part of the verse

- antarā: second exposition of The antarā

- sargam: improvised development on the note names (sargam)

- tān: fast, improvised melodic-rhythmic phrases on the note names (sargam)

- ākār tān: fast melodic-rhythmic phrases on the sound ‘a’

- tihāī: concluding rhythmic phrase repeated three times

Schematic presentation of the development structure

| ālāp | unmeasured prelude |

| sthāyī | first part of the composition |

| antarā | second part of the composition and improvisation |

| sthāyī | return to the first part of the composition |

| tān | improvised melodic movements |

| tihāī | concluding rhythmic phrase repeated three times |

Presentation of the Khayāl genre

Khayāl is characterized by a highly ornamented style conducive to demonstrating virtuosity and The performer's creativity: the more or less fixed part that constitutes the sung poem is the core from which the raga is developed. By following different phases of development and applying various methods of variation and improvisation, the singer "expands" the raga. The term Khayāl, derived from Arabic, means "imagination."

The sung poem (bandiś) represents the quintessence of the raga, that is to say, a condensation of its form (rūp) and its image (shakal), as the musicians express it. Each sung poem reflects a certain image of the raga in which it is composed.

The Khayāl is subdivided into two categories: the baŗā Khayāl (literally “great” Khayāl), which unfolds at a slow tempo (vilambit), in the first part of a recital, using long cycles; and the chṭā Khayāl (“small” Khayāl), which follows it, sometimes without a break, at a medium or fast tempo.

The rāga is developed progressively in the baŗā Khayāl in an exposition that can last from half an hour to 1 hour and 15 minutes, before being treated more rhythmically in the chṭā Khayāl, within a generally different metrical framework, at a brisk tempo.

While the baŗā Khayāl is often presented today in the twelve-beat ektāla cycle, the chṭā Khayāl is frequently in tīntāla, a sixteen-beat cycle.

Lyric poems are composed in one or the other of these forms, as well as in a given rāga and tāla. A Khayāl song consists of two lines, referring to two sections, respectively called the “sthāyī” and the “antarā.” While the “sthāyī” explores the middle register of the rāga, the antarā is centered on the upper register. Each line can be subdivided into two, three, or four sections, marked by a caesura.

The first part of the first verse, which concludes the first beat of the cycle, is called the "mukhṛā". Like the opening of a song, the mukhṛā gives its name to the composition. Similar to the first phrase of the "sthāyī," it is sung throughout the performance, like a refrain to punctuate the improvised sections.

Khayāl songs are generally in Braj, a western dialect of Hindi spoken in the Mathura and Agra region (approximately 150 km south of the capital, New Delhi). Braj is also a literary language: between the 15th and early 19th centuries, it served as the medium of expression for the great saint-poets of North India.

The range of themes addressed in Khayāls is very broad. One finds both sung poems of romantic inspiration and devotional and philosophical themes, as well as songs describing nature and the seasons. The gods of the Hindu pantheon are the subject of numerous praise songs (the goddess, the god Shiva, but especially Krishna). Praises of saints and Sufi spiritual masters are also widespread. Among the other common themes of Khayāls songs is the separation or reunion of two lovers. Some also deal with the power of music and the bond between the artist and their patron, or the artist and their master.

The historical origins of Khayāl are the subject of debate, but this vocal genre is believed to have emerged at the end of the 16th century within the Indo-Persian culture of the Persians princely bears of North India to develop in the following centuries as highlighted by historian Katherine Butler Brown (2010). This view departs from the oral tradition which often attributes the origin of this song to the medieval saint-poet Amir Khusrau (14th century).

Rāga Naṭ bhairav

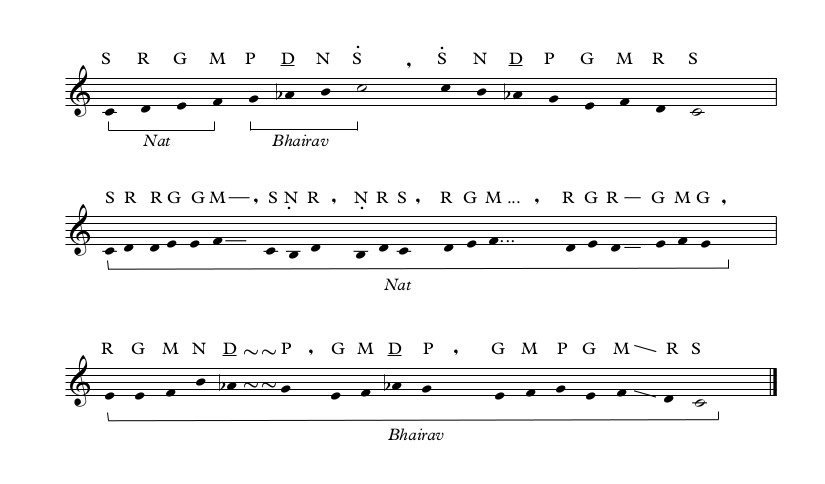

Visual Representation of the Piece

The transcription system, custom-designed for this specific context, presents Indian and Western notations in a complementary manner. For the notation of the unmeasured preludes, ālāp, it draws inspiration from proportional notation, used in contemporary Western music by some composers.

Presentation of the rāga Naṭ bhairav

The Rāga Naṭ bhairav is a variety of the Rāga bhairav, one of the fundamental rāgas of the Hindustani repertoire, traditionally performed at sunrise.

It is a composed rāga, combining elements of the Rāga Naṭ and the Rāga Bhairav.

The main difference from the scale of the latter is the use of a natural second degree (major second) instead of a lowered second degree (minor second).

This is a heptatonic rāga (sampūrṇ) with a lowered sixth degree (minor sixth).

The first and fourth degrees are the important notes of the scale.

The sixth degree is presented with a characteristic slow oscillation (āndolan).

This rāga is recent, having developed in the second half of the 20th century.

The ascending (āroha) and descending (avaroha) scale of this raga and several characteristic melodic phrases are presented below and compared with the ragas Naṭ and Bhairav from which it originates. Performance often presents a more subtle reality.

Raga Nat Bhairav scale - Complete Score

Explanation of the Raga Nat Bhairav by Sudhanshu Sharma.

Presentation of the Raga Nat Bhairav by Henri Tournier

Presentation of the Rhythmic Cycle

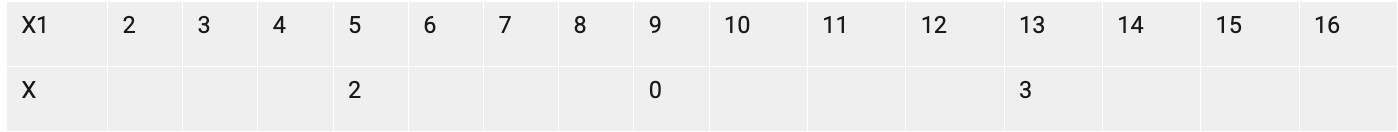

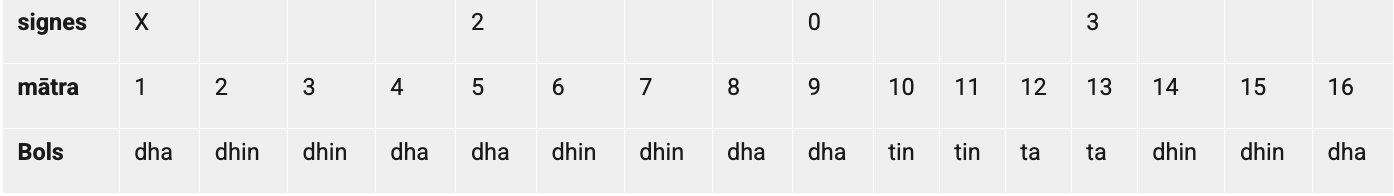

Regarding the rhythmic cycle, or tāla, it is notated below the melody line. The first beat of the rhythmic cycle is the sam, marked by a cross: X.

Each rhythmic cycle is characterized by a number of beats (mātrā), divided into sections (vibhāg) which may be of unequal length.

The numbers indicated on the second line mark the division of the cycle: 0 signifies an unmarked beat, or khālī, and 2, 3, and 4 indicate the marked beats.

Tīntāla is one of the most common rhythmic cycles in Hindustani music. It is divided into four sections of four beats each.

The Division of the Tīntāla Rhythmic Cycle

The strikes of the tablā are represented verbally by bols, sequences of onomatopoeic sounds that embody the ṭhekā, the basic rhythmic phrase characteristic of a given rhythmic cycle (tāla).

The ṭhekā is the specific arrangement of a tāla. The bols allow for the verbalization and memorization of the rhythmic subdivisions of the cycle. Syllabification is central to both vocal and instrumental learning of Hindustani music.

The bowls of tāla tīntāla are: dha dhin dhin dha / dha dhin dhin dha / dha tin tin ta / ta dhin dhin dha

Saptak Sharma plays an addha tāla, a variation of tīntāla.

Video explaining the rhythmic cycle by Saptak Sharma

Notation System and Specialist's Perspective

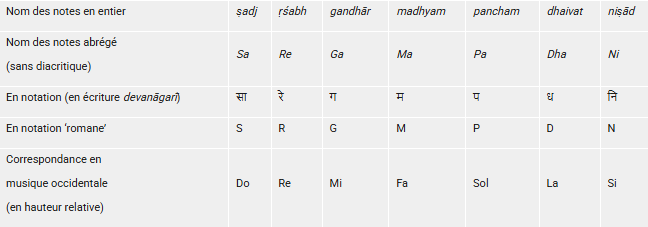

The Indian System of Musical Notation

In the context of Indian classical music, notation primarily serves as a memory aid, since learning is mainly achieved through listening, memorization, and repetition. Hindustani music remains, in fact, a music of oral tradition.

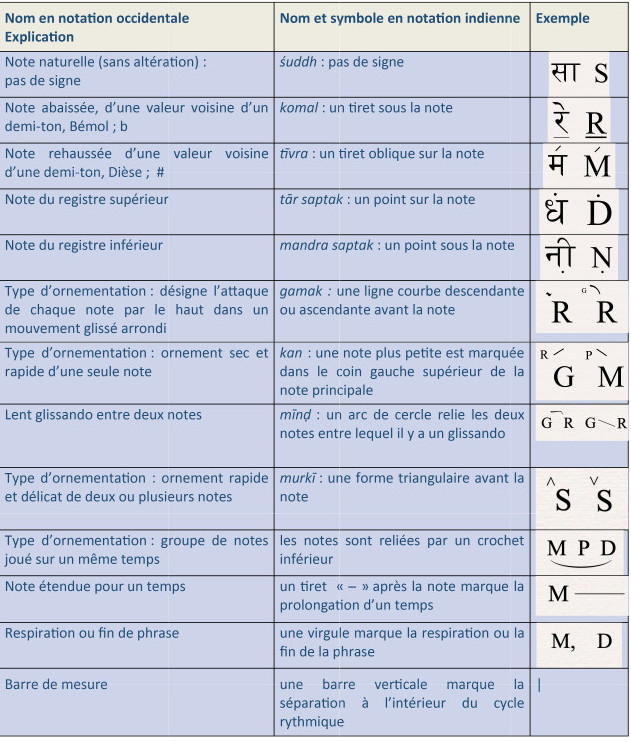

The Hindustani musical system is a syllabic system that uses seven notes or degrees, which are abbreviated as shown in the following table. The notes of the Indian system (Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha, Ni) can be related to the seven notes of the Western scale (do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si).

However, the reference note Sa has a variable pitch: depending on the singer's vocal range and the instrument played, the fundamental can vary.

The Hindustani musical system places great importance on the intervals between notes, particularly the interval between a given degree and the fundamental, which is continuously recalled by a drone accompanying every performance. The manner of attacking or ornamenting a note, and the way several notes are linked together, are characteristic elements of certain rāga. Not all of these ornaments can be precisely transcribed.

To facilitate transcription and reading, we have here equated Sa with the C of the Western musical system.

In the Hindustani melodic system, the reference note (Sa) and the fifth (Pa) cannot be altered: the first and fifth degrees of the scale are fixed. While the second, third, sixth, and seventh degrees (Re, Ga, Dha, and Ni) can be lowered (komal), only the fourth (Ma) can be raised (tivra).

Names of Indian Notes and Their Notation

The scale uses twelve semitones or degrees of adjustable pitch (the concept of śruti or micro-interval) and spans three registers: lower (mandra), middle (madhyam), and upper (tār).

A dot below the note indicates that it is played in the lower register, and a dot above it indicates that it is played in the upper register. The term saptak refers to the series of seven degrees of the scale.

The usual symbols of the Indian notation system, or "sargam" notation (named after the first four notes of the scale), are presented in the following table.

The notation system considered here is the "Bhatkhande" system, which is currently the most widely used system in North India. It is named after the musicologist who developed it, Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860-1936).

The main symbols used in Indian musical notation (in the Bhatkhande system). The transcription system, custom-designed for this specific context, presents a complementary parallel between Indian and Western notation. For the notation of unmeasured preludes, ālāp, it draws inspiration from proportional notation, used in contemporary Western music by some composers.

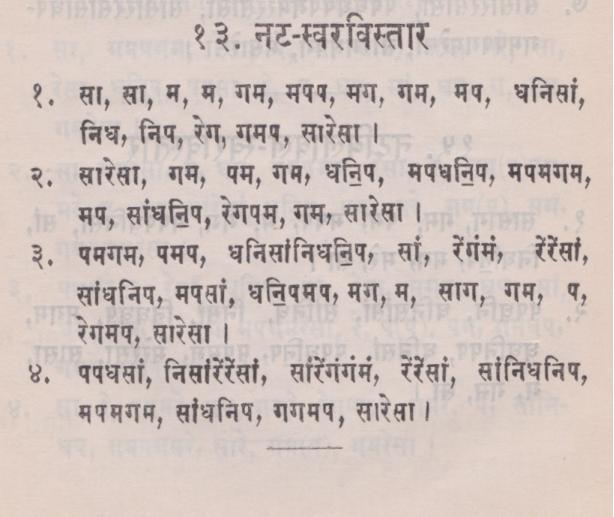

Raga Nat - Swara vistar (melodic movements - combinations of notes) Excerpt from Kramik Pustak Malika - Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati (volume 5) by Pt. V.N. Bhatkhande

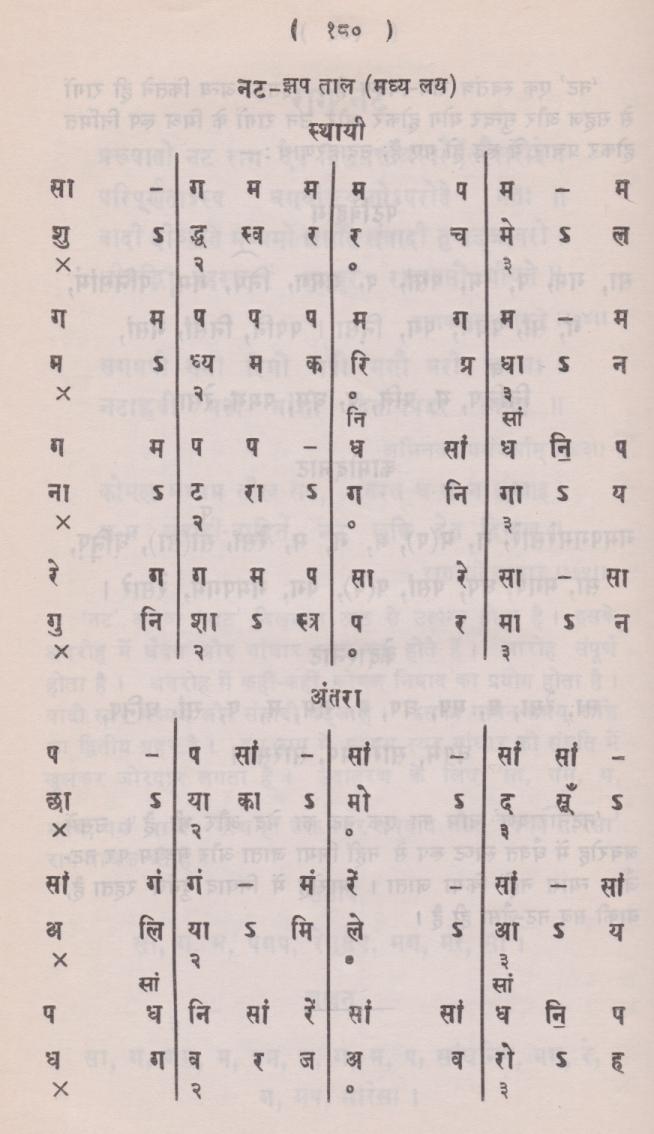

Raga Nat - Composition in Jhaptala (10 beats), Madhya Laya (medium tempo) Excerpt from Kramik Pustak Malika - Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati (volume 5) by Pt. V.N. Bhatkhande

For Indian rhythmic notation, the writing system is that of the musicologist Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande:

- a unit of time is represented either by a small line, the first letter of a note name, or a horizontal loop

- within each horizontal loop, that is, within each unit of time, are placed the notes and rests.

Since this notation is primarily a memory aid, neither the resonance of the notes, nor the phrasing connections, nor the nuances are indicated.

Henri Tournier on Sudhanshu Sharma's interpretation

Henri Tournier on Sudhanshu Sharma's interpretation

"Sudhanshu Sharma chose a structure for developing the rāga Naṭ bhairav that was adapted to the short duration desired for the custom-made recording for the website.

He begins not with an ālāp but with what is called an aochar, a short sketch that presents the characteristic movements of the raga, in order to establish its identity before developing it further. An ālāp would have required more time to go beyond a simple presentation and truly explore the beauty of the rāga's melodic resources."

Next, Sudhanshu Sharma presents a composition and its poetic text (bandiś) in the raga Naṭ bhairav, accompanied by the tabla, built on a 16-beat cycle called addha tāla, a kind of variation of the tīntāla cycle, the major rhythmic cycle, which can be interpreted, depending on the chosen tempo, as a 16-beat cycle, but also as 32, 8, or 4 beats. Performed at this tempo, this 16-beat cycle is perceived as an 8-beat cycle.

Sudhanshu Sharma first presents the part of the composition that the composition begins around the middle tonic, a section called sthāyī, consisting of a main phrase and a development phrase. Then, the developed section, called antarā, begins around the tonic of the upper register, using ascending movements. This section also consists of a main phrase and a development phrase.

This exposition of the composition, played in variations, concludes with a return to the main section, centered on the middle tonic, the sthāyī.

Then, Sudhanshu Sharma focuses on developing improvised sequences that conclude with this middle section (sthāyī). These sequences, more lyrical than rhythmic, incorporate elements of the ālāp prelude, an improvised piece centered around a single note, with a limited choice of notes. They are developed gradually, in a generally ascending movement. When he reaches the upper register, Sudhanshu Sharma plays the upper part of the composition, its development, and returns to the sthāyī.

Then, at a slightly faster tempo, he develops a more rhythmic style, sung in sargam, the notes of the Indian scale. At an accelerated tempo for the second time, he constructs tān, phrases or garlands of virtuosic notes sung first in sargam, with the names of the notes, and finally in ākār, vocalizing on the vowel "a".

To conclude, he returns to the sthāyī and repeats a short motif from this melody, repeated three times identically, called a tihāī. On the last note of the tihāī, the tabla stops playing, and Sudhanshu Sharma sings a short phrase similar to the movements of the prelude, allowing him to return to the peaceful character of the beginning of his performance.

The improvised elaboration structure proposed by Sudhanshu Sharma is perfectly suited to the context of a short 10'30" presentation: despite this time constraint, it allowed him to present a very complete range of the constituent elements of the rāga Naṭ bhairav.

Rāga Naṭ bhairav

Khayāl song:

- Ustad Amir Khan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Crwj1Ze2T-A

Instrumental versions:

- Pandit Ravi Shankar :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RbyTj9FVyjg - Ustad Ali Abkar Khan : live at Sawai Gandharva Mahotsava (1982)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdcIR3tB5Xo - Nikhil Banerjee : Music video by Pandit Nikhil Banerjee performing Raga Nat Bhairav in 1975

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Meq8Fr7hvF0

Context of the performance

Hindustani music, better known today as "North Indian classical musi", is a concert music that was primarily court music until the mid-20th century. Until the 1950s, artists from communities of specialist musicians were indeed in the service of princely and royal courts, or performed in the salons of large landowners and wealthy merchants, as well as in the salons of courtesans.

Hindustani music is now performed in the major halls and auditoriums of North India's largest cities, as well as on international stages.

The audience plays a crucial role in a Hindustani music concert: the level of listening and understanding of the audience contributes significantly to the quality of the performance. The concert aims to share a feeling (bhāva) and create aesthetic pleasure (rasa) in the listener. The knowledgeable audience expresses its appreciation through hand gestures, head movements, and verbal interjections.

A Matter of Learning and Transmission

Although there is institutional teaching of Hindustani music, oral transmission from master to disciple—known in India as guru-śiṣya-paramparā—remains the primary mode of transmitting this musical knowledge. Training with a master is the preferred path to becoming a professional Hindustani musician.

In this context, the lesson is based primarily on listening to and observing the master's gestures, as well as on memorizing and repeating the elements taught.

The teaching of the rāga follows the presentation format adopted in a performance context. The teacher or master (guru) first teaches the introductory section of the rāga (ālāp). The lyric poem or composition is then taught. The song is broken down by the master and repeated section by section by the student. The student simultaneously integrates the fixed elements of the performance—namely, the grammar of the rāga, the metrical framework of the tāla, and the lyric poem—with the fluid elements of the improvised sections (the ālāp, the tāns, etc.). A Khayāl constitutes a textual and musical unit: it is conceived as a song that is learned in its entirety, encompassing both its melodic and rhythmic forms.

Therefore, one sings a rāga as one has learned it from the master, through imitation and the gradual assimilation of its form.