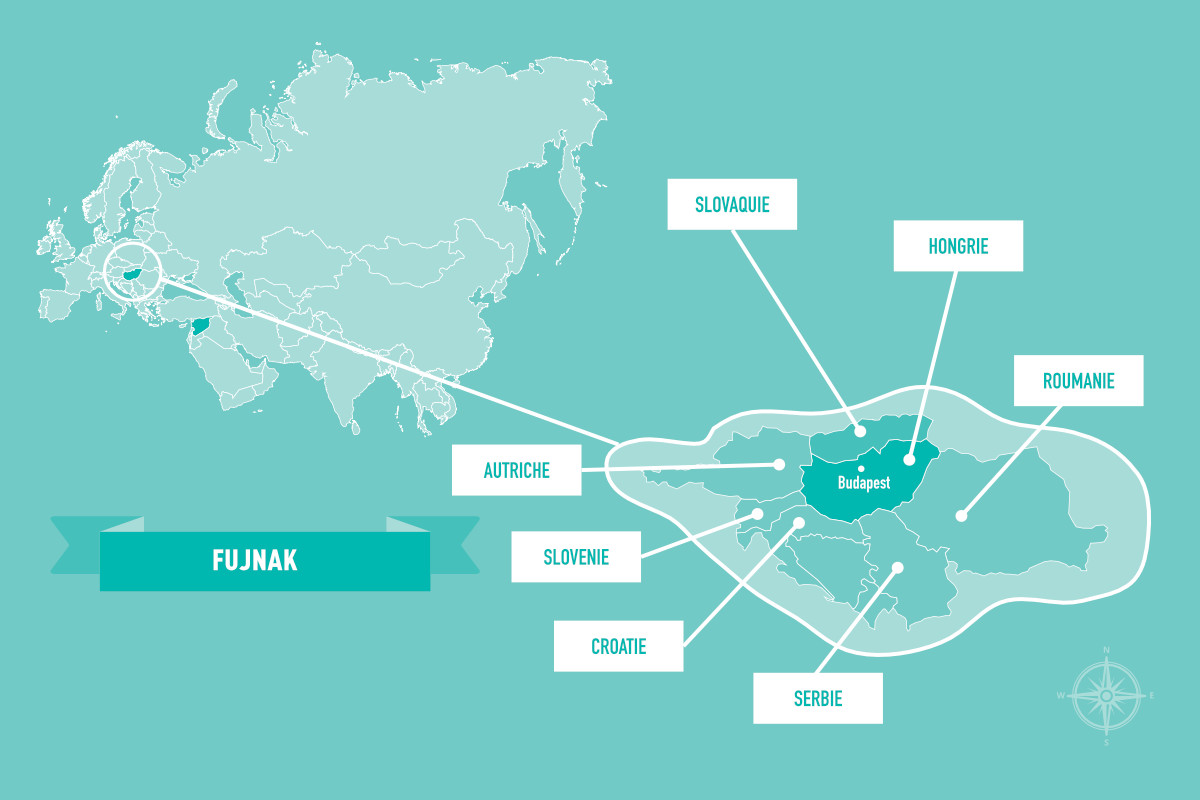

Hongrie

Fújnak a fellegek

-

Genre :Popular music

-

Tradition :Southern Transdanubia

-

Piece name:Fújnak a fellegek

-

Specifics:Páva music

The song whose literary incipit is Fújnak a fellegek Somogy megye felől : "The clouds are blowing from the county of Somogy" , was performed a cappella by Szakáll Józsefné "Miklós" Bebők Judit "Dávid" in Nemespátró, in the county of Somogy, in Transdanubia , southwest Hungary, in 1969.

The recording, made by Imre Olsvai and Pál Sztanó, is kept in the Archives of the Institute of Musicology of the Research Center for Humanities under the archive number AP_6686l.

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Archives of the Institute of Musicology of the Research Center for Humanities ( 1014 Budapest, Táncsics M. u. 7.)

Fújnak a fellegek Somogy megye felől

The song, whose literary incipit is Fújnak a fellegek Somogy megye felől, "Clouds are blowing from Somogy County", is performed by Szakáll Józsefné "Miklós" Bebők Judit "Dávid".

This is her full name in common use: in Hungarian, the family name is followed by the given name. Married women often take their husband's first and last name followed by the suffix "né" ("wife of...") and add their maiden name and first name.

Szakáll Józsefné was born in 1900, so she was 69 years old at the time of this recording.

This song was recorded on November 22, 1969 in Nemespátró, Somogy County in Southern Transdanubia, by Imre Olsvai and Pál Sztanó in 1969.

Imre Olsvai (1931-2014) was an ethnomusicologist, pedagogue, composer, member of the Department of Ethnomusicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (see the article by Domokos, Mària, 2020, “Imre Olsvai.” Oxford Music Online, Grove Music Online).

Pàl Sztanò (1928-1997) was a sound engineer and sound restorer, member of the Department of Ethnomusicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (see the article “Sztanò Pàl”, n.d., Digitàlis Muzsika, http://epa.oszk.hu/00800/00835/00177/Mk_1997_08_17sztano.htm).

The recording is held in the archives of the Institute of Musicology of the Research Center for Humanities under the archive number AP_6686l. It is accessible online at the following URL: http://db.zti.hu/24ora/mp3/6681l.mp3

A selection of the archives is accessible from the website of the Institute of Musicology of the Research Center for Humanities at the following address: http://db.zti.hu/

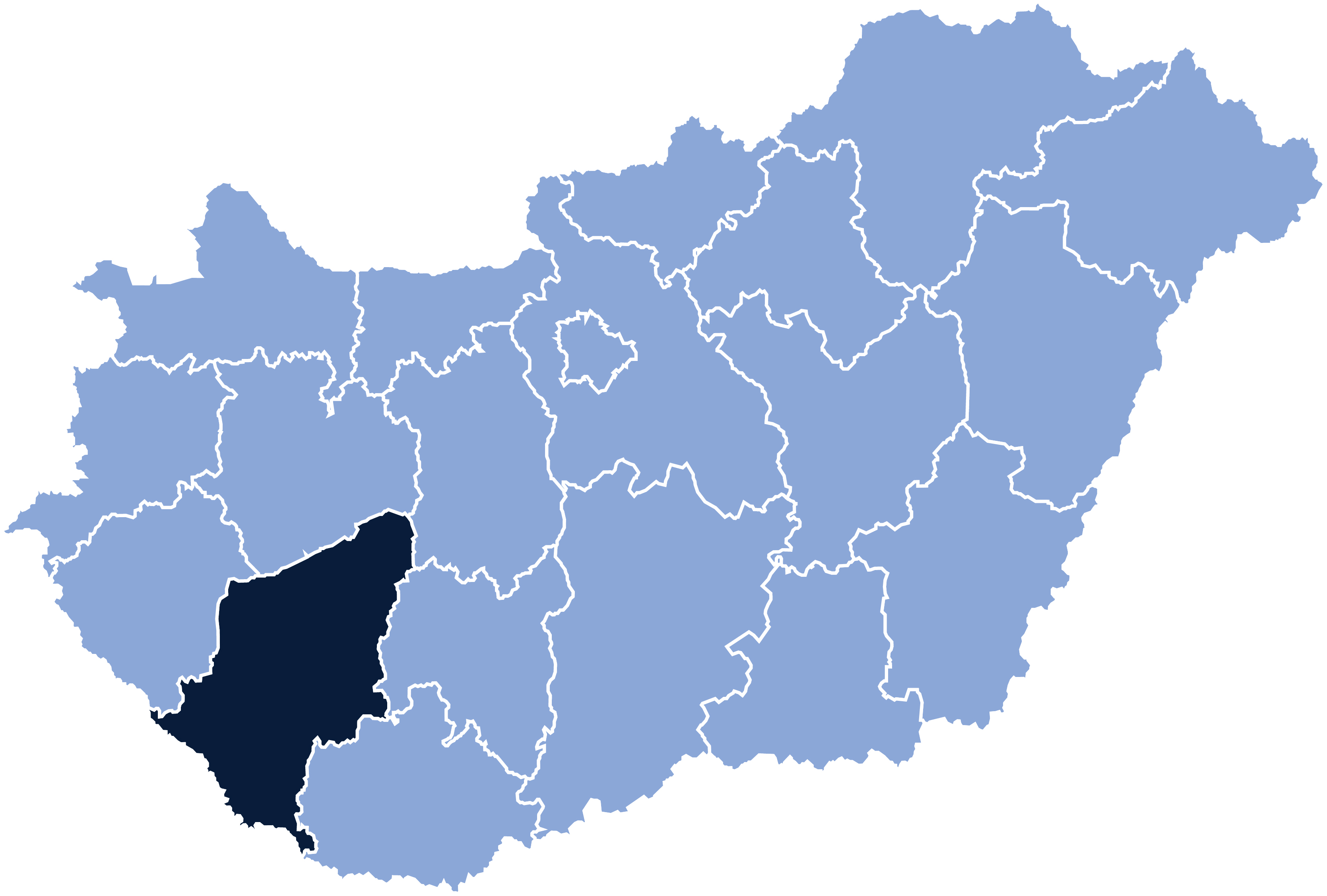

Somogy County in Hungary. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Structure of the song: poetry, melody, rhythm

Here is the text of the song and its sequence:

Literal translation of the song Fújnak a fellegek Somogy megye felől

1st verse:

Clouds blow from Somogy County

I have thought a lot about our destiny

2nd verse:

I have thought a lot about it before

Beside Your Majesty, our destiny is engraved

3rd verse:

I have thought a lot about our ancestors and our wanderings in this world.

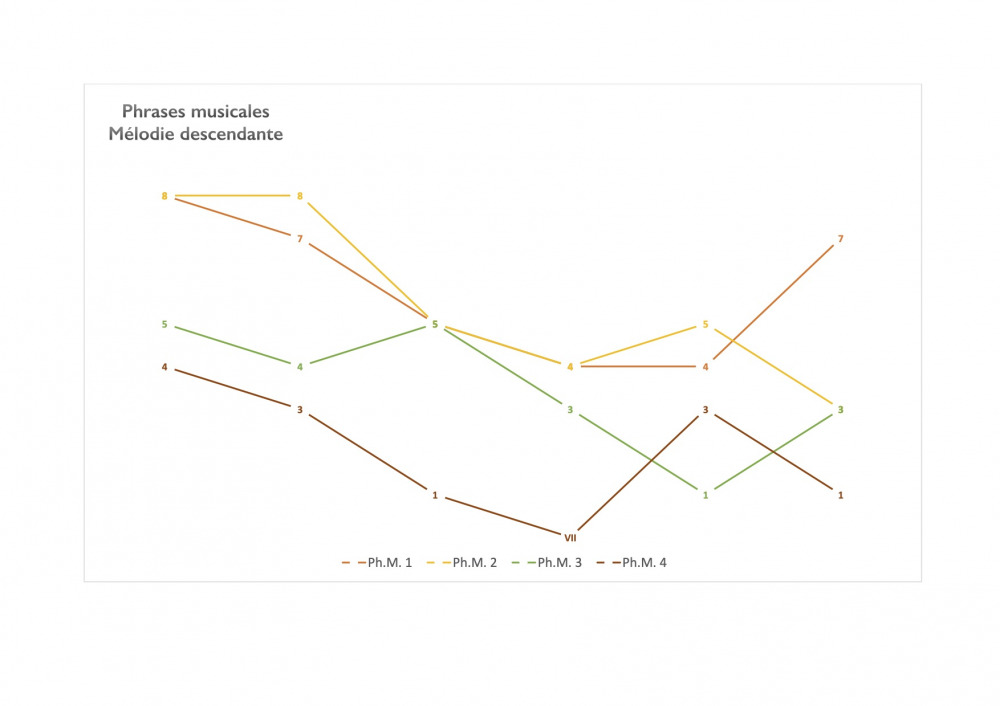

The melodic-rhythmic structure of the song Fùjnak a fellegek

The song has a fixed structure; it is strophic: the lyrics (four isometric poetic verses, each containing six syllables) are set to music by four musical phrases. In the first and second stanzas, the third and fourth musical phrases are repeated with the corresponding lyrics, while in the third stanza, the singer does not repeat them.

The verses are isometric; they contain the same number of syllables: 6, 6, 6, 6.

The final grade system

7, [3], 3

In the classification of the sixth volume of Magyar Népzene Tára, Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae, the chant is classified among the melodies of the final note system: 7, [b3], b3.

According to the tradition of Hungarian musical analysis and relative solmization, the final notes of musical phrases are symbolized by numbers. Since the chants are transcribed with the final note "g," the final note of the last musical phrase is considered 1 and is never indicated. Thus, the three numbers indicate that this strophic chant contains four musical phrases. (In cases where the final note of a musical phrase falls below 1, it is symbolized by the Roman numerals VII, VI, V, etc.).

Imre Olsvai notes that "in strophic chants, the most important and easily perceptible characteristics are the number of musical phrases that contain the syllable structure of the verses and the system of final notes (kadenciakèplet)." He adds that in classifications, "these two characteristics have main functions." (Olsvai, 1998, p. 523).

The melodic design of Fùjnak a fellegek

The melodic pattern of the song is descending.

Here it is represented according to the practice of musical analysis of traditional Hungarian oral songs, using the final note system.

The melodic drawing of Fùjnak a fellegek, performed by Zsòfia Pesovàr

The principle of classifying Hungarian oral songs based on their melodic design was developed by Pàl Jàrdànyi (1920-1966), ethnomusicologist and composer. Jàrdànyi first observed the melodic design of the songs in their entirety, and then examined the relationships between the musical phrases. According to Jàrdànyi, in Hungarian oral music, there is no first musical phrase lower than the last. He thus established two broad classes, each containing several groups and subgroups:

1. The first musical phrases are higher, sharper, than the last ones.

2. The first and last musical phrases are analogous. (Jàrdànyi, 1961, p. 178).

The songs in the first group roughly coincide with the old style of Bartók's classification. The songs in the second group are in line with those of the new style.

In the introduction to the sixth volume of Magyar Népzene Tára, Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae, Imre Olsvai writes the following: "We can supplement these two main groups with the third, in which we classify melodies whose first musical phrase is always lower than the last." (Olsvai, 1973, p. 19). According to the observations and analyses of ethnomusicologists, in this third group we do not find any characteristic Hungarian songs; these melodic-rhythmic structures developed from written music or folk music of foreign origin (Olsvai, 1973, p. 19).

Intervals, Scales, Ranges

The Scale

Hungarian ethnomusicologists note that in pentatonic tunes performed in Transdanubia, the pitch of the third can be slightly lower than in other musical dialects. According to Hungarian ethnomusicological terminology, this third is called the "Transdanubian third" or the "Neutral third." When the song was transcribed, this third can be indicated by the diacritic mark: ↆ

The Range

The range of the melody (i.e., the range of sounds used in the song) is 8 – 7, according to the graphic representation system we have adopted.

The song is performed in parlando rubato.

Based on these characteristics, this song is classified as an old-style pentatonic melody. The descending fifth structure is perceptible in the traces observable by examining the four musical phrases.

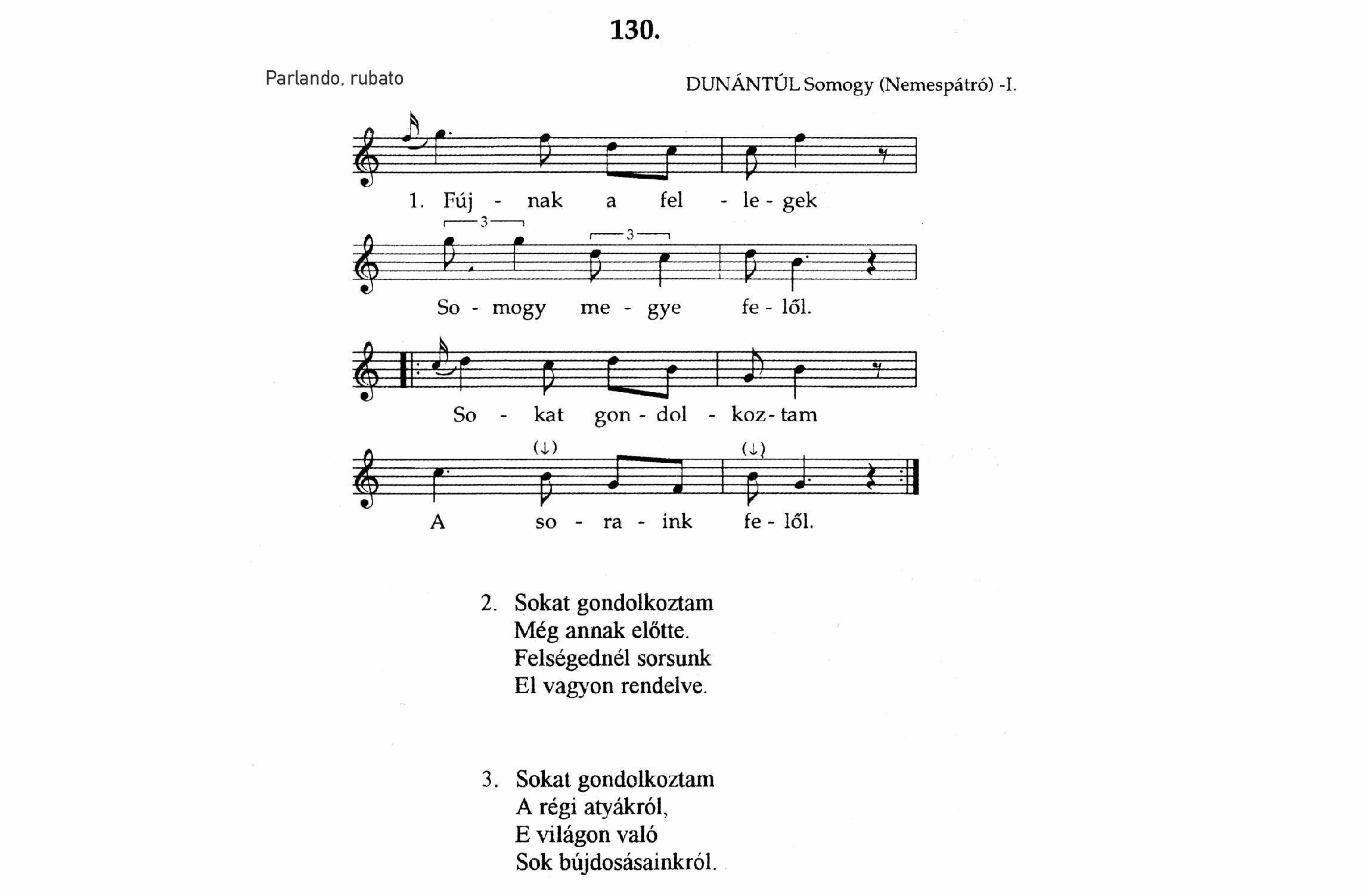

Transcription on score and analysis

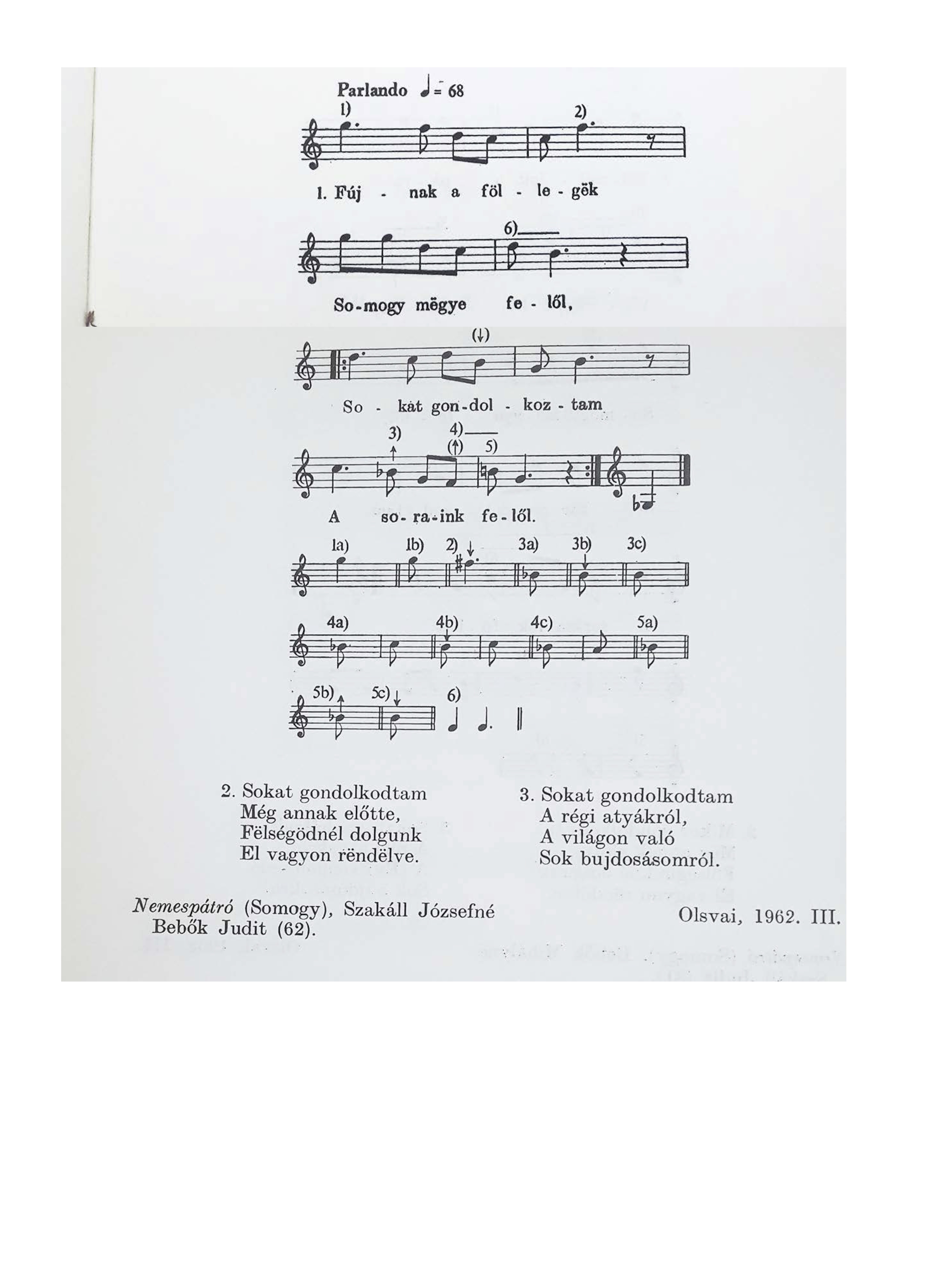

Score of Fújnak a fellegek by K. Paksa and K. Bodza, 1997.

This score is taken from Paksa, Katalin and Klàra Bodza, 1997, Magyar nèpi ènekiskola, vol.1. Budapest: Magyar Nèpművelèsi Intèzet Néptàncosok Szakmai Hàza, p.171, n°130.

The function of the score in learning oral tradition singing

The notation of melodies, rhythms, and lyrics in oral tradition songs is always approximate: it offers only relative accuracy, as the transition from musical listening to transcription results in a loss of data.

Regarding the melodic-rhythmic components, certain information that carries meaning disappears: the speed of interpretation, the slowing down or acceleration during performance, the accentuation, intensity, duration, and pitch (vibration frequency) of the sounds; the rhythmic and melodic details of the ornamentation, the timbre of the voice, the interpretation, that is, the personal subtlety of the performance, the individual vision of the song.

The notation of the spoken word also does not provide precise indications, because the letters of the alphabet do not express the subtlety of the exact pronunciation of the phonemes that, among other things, provide the characteristics and colors of linguistic dialects.

To provide precision and approximate perceptible reality, transcribers frequently use "diacritical" signs. In this musical transcription, the arrow ( ↆ ) indicates that the pitch of the sound in the oral performance is slightly lower than the pitch indicated on the staff. This indication is not precise. Nevertheless, when reading the score, this sign draws the learner's attention to the pitch of the sound as well as to the "fragility" of the musical transcription.

Consequently, when learning, the score accompanied by the text serves as a memory aid. Listening to the sound recording is essential for mastering the melody and the lyrics.

The practice of musical transcription by Hungarian ethnomusicologists

According to the tradition of Hungarian ethnomusicology, oral songs are transcribed with the final note "g," regardless of the absolute pitch of the performance and vocal range. This practice began at the dawn of Hungarian ethnomusicology because transposition to the same pitch facilitates comparative analysis and classification of the collected songs.

The final note "g" (written on the second line of the staff) is identical to "sol" (used as a denomination in the French system). Indeed, two systems of naming absolute tones exist in Western musical practice. One uses the Latin alphabet to name the notes corresponding to a vibration frequency, and the other system uses the first syllable of the lines in the first stanza of the Hymn to Saint John the Baptist, written by Paul the Deacon in the 9th century, to name the solmization syllables since Guido of Arezzo. In Hungary, both systems are used. The naming of sounds according to the Latin alphabet is used to describe absolute pitch. The names taken from the Latin hymn are used in relative solmization, where a sound is defined according to its relationship to other sounds.

Transcription, a graphic trace of the song

The poetic-musical structure is discernible through the distinction between the musical phrases (accompanied by the corresponding verses). In this score, each phrase is transcribed separately on a different staff. The division of the transcription visually represents the structure of the song. In this case, the four lines of the stanza are set to music by the four musical phrases.

Hungarian ethnomusicologists generally transcribe the first stanza in its entirety.

Depending on the purpose of the edition, the published transcription is more or less complex: for ethnomusicological analyses, the rhythmic and melodic variations that form throughout the performance are indicated in relation to the first stanza. They are annotated and transcribed separately with the corresponding text, indicating the stanza number where they occur. Exclusively rhythmic variations do not require the use of a staff.

Additional information accompanying the musical transcription

The additional information contextualizes the musical transcription and provides information about the recorded music. Depending on the purpose of the publication, these details vary in detail:

- the performer, specifying their first and last name, and date of birth,

- the place and date of the recording,

- the first and last name of the researcher,

- the first and last name of the transcriber,

- the absolute pitch of the song, starting from the "a" sounded by a blown tuning fork that precedes the recording,

- the performance mode (giusto, parlando, rubato, etc.).

For this song, the additional information includes the recording location, the musical dialect, and the performance mode.

The collection location and the musical dialect

The place where the song was collected is noted on the right-hand side, below the transcription, and is followed by a Roman numeral I, which indicates the musical dialect. The concept of musical dialect was introduced by Bèla Vikàr (1859-1945).

A linguist, translator, and ethnologist, Vikàr first used the Edison phonograph in Europe in 1895 and presented his recordings in Paris at the 1900 World's Fair (Sàndor, 1982, p. 538). He made phonographic recordings in the territory of the Hungarian language. Based on his observations during his linguistic studies, Vikàr proposed the introduction of the term "musical dialects": "Similar to linguistic dialects, there are musical dialects. According to my current observations, musical and linguistic dialects are inseparable" (Vikàr, 1901, p. 14).

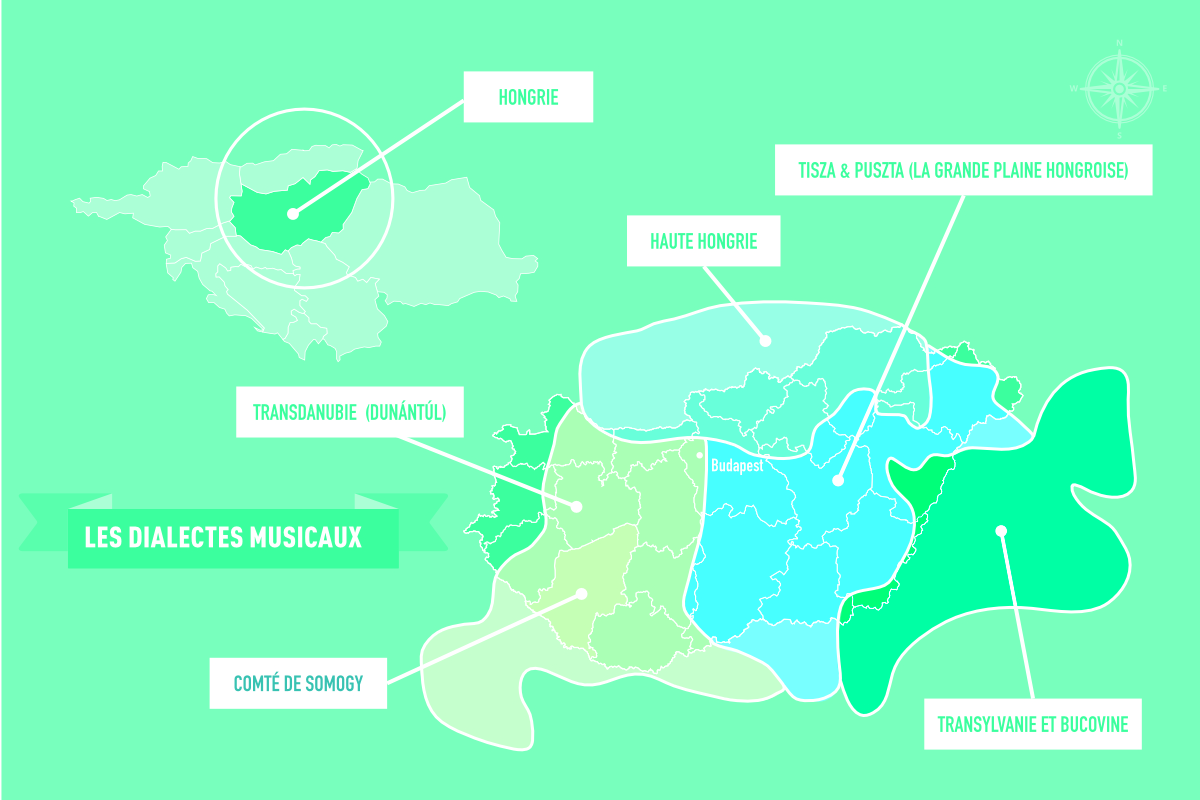

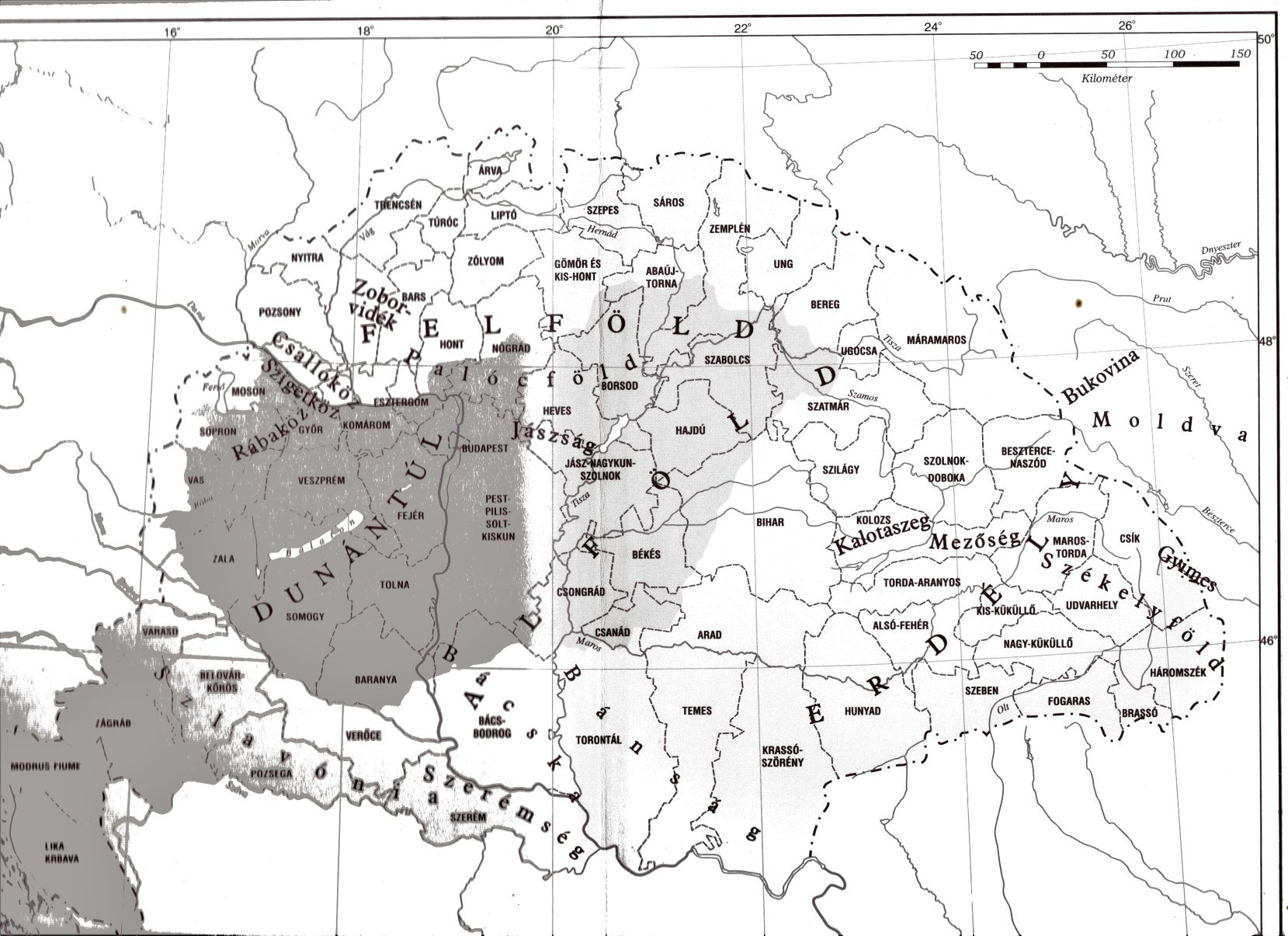

Through a comparative analysis of songs collected from different Hungarian-speaking territories, composer, pianist, and ethnomusicologist Bèla Bartòk (1881-1945) distinguished four musical dialects in 1922 :

- Transdanubia (This musical dialect includes the villages inhabited by Hungarians in Slavonia.)

- Upper Hungary, north of the Danube (which includes some villages inhabited by Hungarian minorities in Slovakia)

- The Tisza region or Puszta (the Great Hungarian Plain)

- Transylvania, including Bukovina (the Hungarian minorities living in Romania).

Following Bartòk's work, ethnomusicologists completed this division with a fifth dialect encompassing "Gyimes" and "Moldva" (these territories are part of Romania and are inhabited by Hungarian minorities). Following ethnomusicological investigations, the description of musical dialects became more and more detailed and sub-dialects gradually emerged (Olsvai, 1998, p. 527).

Musical dialects in Hungary, according to Bargyas, 2002

Map taken from VARGYAS Lajos, 2002, Magyarsàg nèpzenèje, 2nd ed., Budapest: Jelenlèvő Mùlt.nèpzenèje, 2e ed., Budapest : Jelenlèvő Mùlt.

The musical performance of the piece

Borrowed from musicology, the technical terms "parlando / rubato" concern the performance of singing. These indications are written on the left side, below the score. Unlike tempo giusto, which indicates a constant and regular pulse, parlando indicates that the performance of singing occurs according to the spoken language, and rubato indicates that in the performance, the alternation of strong and weak beats is irregular. Emotions, a subjective "pulse," take precedence over rhythmic expression: the rhythm and accentuation of the words take precedence over musical rhythm.

The specialist in the tradition in question

Comparative analysis and classification of the Fùjnak a fellegek song according to Hungarian ethnomusicology

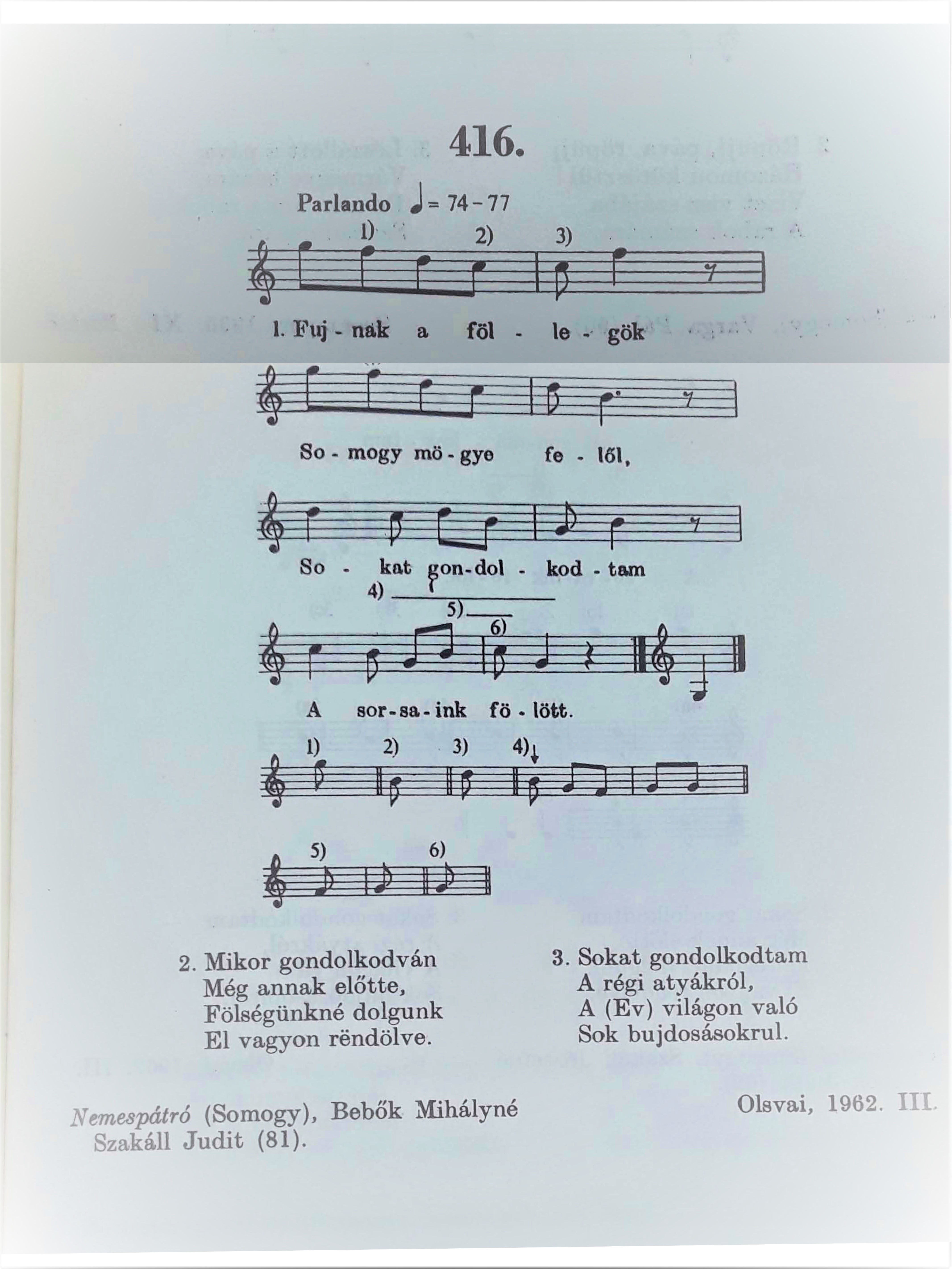

Another score of the song is available in:

BARTÒK Bèla and Zoltàn KODÀLY (1973) Magyar Népzene Tàra. Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae. (P. Jàrdànyi & I. Olsvai, Eds.; Vol. 6). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadò, p. 369-370, n°417.

Archive number: 6681l.

Incipit: Fújnak a fellegek Somogy megye felől

Name of performer: Szakáll Józsefné “Miklós” Bebők Judit “Dávid” born 1900

Recording by Imre Olsvai and Pál Sztanó

Registered: 22.11.1969 in Nemespátró – Somogy committee – Transdanubia

URL: http://db.zti.hu/24ora/mp3/6681l.mp3

In the VIth volume of Magyar Népzene Tára, Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae, the song whose literary incipit is Fùjnak a fellegek… is classified among the twenty examples of type IX.

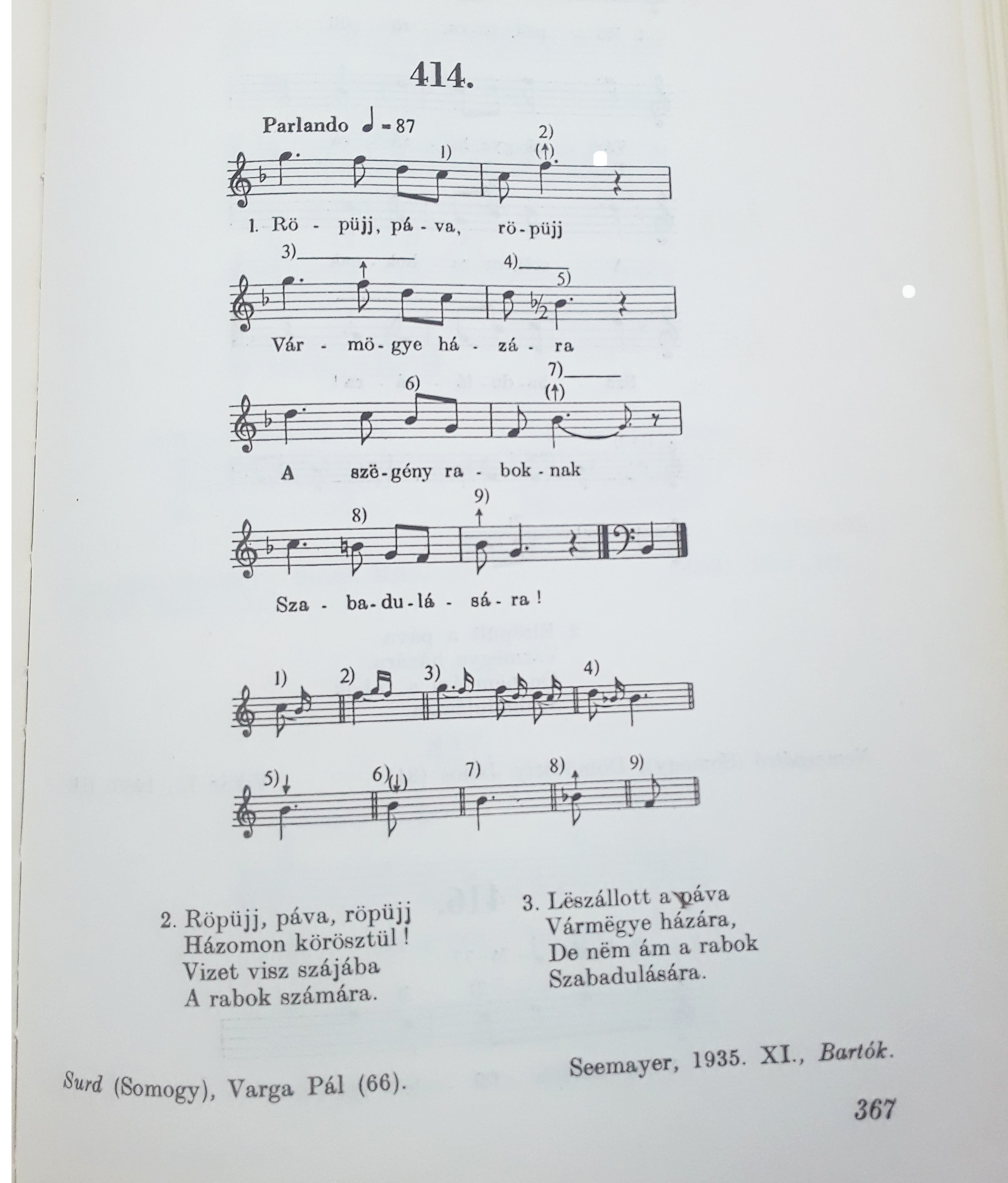

This type, also called the "peacock" family of melodies, received its name from the song whose literary incipit is "Röpülj, pàva röpülj…" ("Fly, peacock, fly…").

According to Olsvai, 1973, p. 19: "This 'peacock' type encompasses parlando, rubato songs of isometric verses comprising six syllables per verse. The main final note is always lower than five; at the end of the first musical phrase, we find a climbing leap in a fourth."

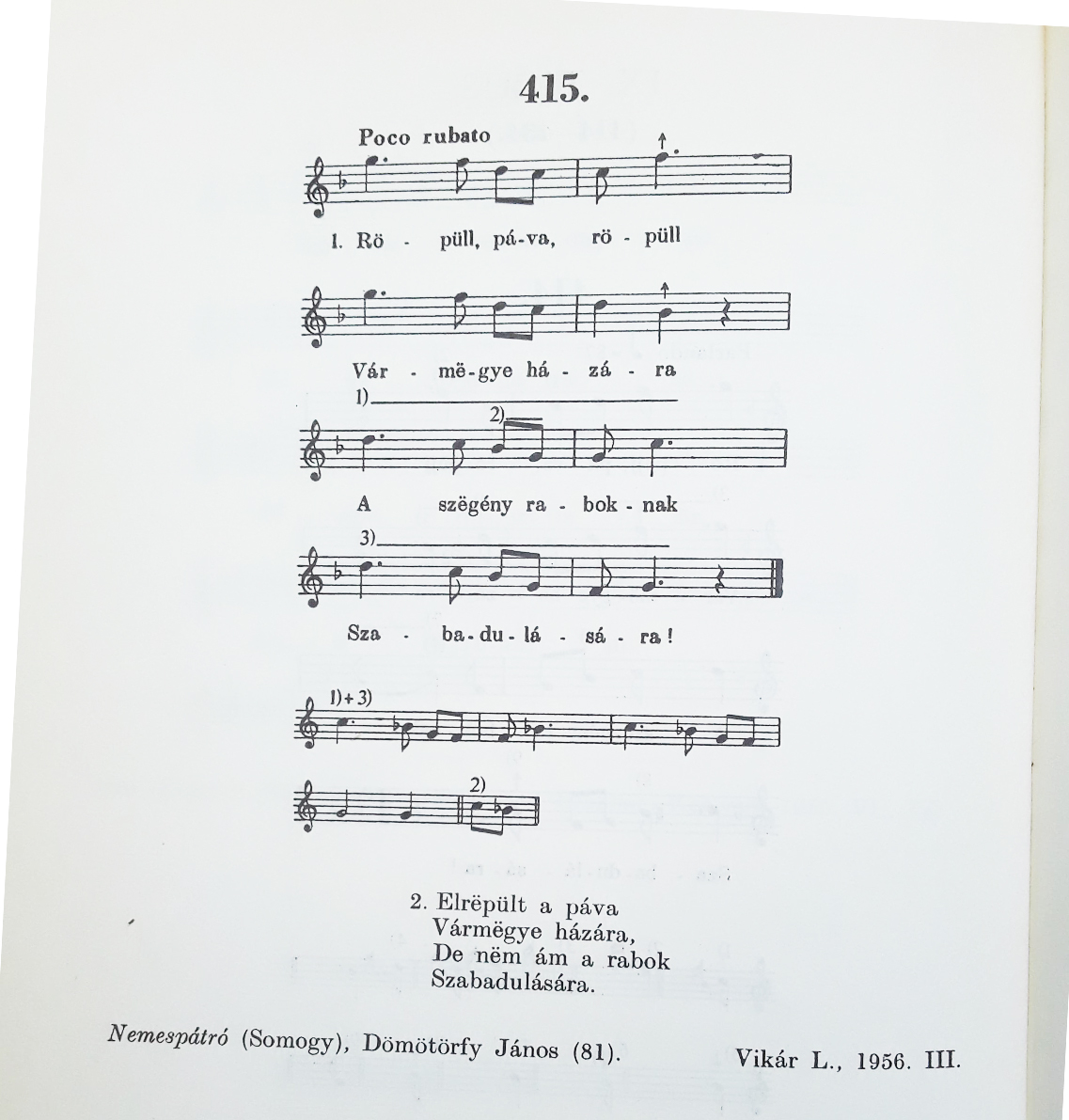

Here is the transcription of two of these "peacock" songs:

In. BARTÒK Bèla and Zoltàn KODÀLY (1973) Magyar Népzene Tàra. Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae. (P. Jàrdànyi & I. Olsvai, Eds.; Vol. 6). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadò, p. 367, no. 414.

Incipit: Röpülj, pàva röpülj… / Fly, peacock, fly

Performer's name: Pàl Varga (66 years old)

Recording by Vilmos Seemayer (1879-1940), geologist, ethnologist, ethnomusicologist

Recorded in 1935 in Surd – Somogy County

Transcriber: Bèla Bartòk

Song translation:

1st verse: Fly, peacock, fly to the county prefecture for the release of the poor prisoners!

2nd verse: Fly, peacock, fly through my house! In its beak, it carries water for the prisoners. 3rd stanza: The peacock has landed on the prefecture, but not for the release of the prisoners.

Transcription of another “peacock” type song:

Transcription In. BARTÒK Bèla and Zoltàn KODÀLY (1973) Magyar Népzene Tàra. Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae. (P. Jàrdànyi & I. Olsvai, Eds.; Vol. 6). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadò, p. 368, No. 415.

Incipit: Röpülj, pàva röpülj… / Fly, peacock fly

Performer's name: Jànos Dönötörfy (81 years old)

Recording by Làszlò Vikàr (1929-2017), ethnomusicologist

Recorded in 1956 in Nemespàtrò – Somogy County

Translation:

1st verse: Fly, peacock, fly over the county prefecture for the release of the poor prisoners!

3rd verse: The peacock flew over the prefecture, but not for the release of the prisoners.

The Musician of Another Tradition

Learning Commentary on the song Fùjnak a fellegek by Rozenn Talec, traditional Breton singer

In this transdanubian and meditative song about the destiny of Hungary, the winds blow.

The arrhythmia of the air evokes reflection and the passing of time, while also creating a soothing sense of questioning.

This song could be likened to a gwerz, this Breton song kan a boz, a cappella, where the words help shape the depth of the interpretation. The melody is then only a pretext, and the sounds transport us into the story of a tragic lament.

My approach of listening to the elders and learning "by ear" allowed me to learn this song more easily.

This learning method allows the development of a memory other than visual memory. Indeed, the text does not transcribe the pronunciation of certain letters or phonemes. The text support can come to him at a later stage. Finally, translation can also help with interpretation.

Interpretation and Aesthetic Heart of Fújnak a fellegek

Interpretation

The execution of this sung poetry from the oral tradition is remarkable in its simplicity. The moderate tone characterizes the interpretation.

Lyric Poetry from the Oral Tradition

This lyric poem briefly expresses philosophical reflections on human life and the past of a people. A metaphorical image, the parallel between the course of clouds and the succession of thoughts, opens the poem. Reflection as an intellectual act is an important motif in this poem and is repeated in each stanza: "I have thought a lot..."

In the three stanzas, the ideas arising in the human mind evoke:

- collective destiny: "I have thought a lot about our destiny..."

- predestination: "Beside Your Majesty, our destiny is engraved."

- ancestors, the history of Hungary.

The last word "bùjdosàs" ending the third stanza can express wandering, vagrancy, or exile. In Hungarian history, after the War of Independence and the failed revolutions, leaders and many soldiers took the path of exile. These traumatic historical episodes become motifs and often recur in songs from the oral tradition.

Songs from the oral tradition are classified according to the semantic content of the texts. Some songs, which deal in detail with the motif of exile, are grouped under the category of songs of exile.

Musical Characteristics of Performance

In his major book, A magyarsàg nèpzenèje [Hungarian Folk Music], ethnologist and ethnomusicologist Lajos Vargyas (1914-2007) writes that in geocultural territories where the "neutral" third appears in songs, we can also observe the existence of the "neutral" seventh.

The "neutral" third is the characteristic intonation in pentatonic songs in Transdanubia, but we observe it sporadically in Zoborvidék (Zobor, a peak in the southern part of Mount Tribeč in Slovakia). The fluctuation of the intonation of the third in pentatonic songs performed in Transdanubia is a stylistic feature. In instrumental music, and more particularly on the violin, the neutral third appears regularly in the playing of gypsy musicians (Vargyas, 1991).

Hungarian Musicology: Analytical Systems and Transmission Issues

Brief Historical Context

The Practice of Musical Analysis of Oral Tradition Songs in Hungary

At the dawn of Hungarian ethnomusicology, researchers sought to establish a classification of collected songs. This classification examines and compares the melodic-rhythmic and metrical characteristics of the songs. This involves comparing songs collected from different musical dialects, from neighboring and related peoples. The influence of art music on folk music was also studied.

The constituent elements of the songs are established based on the principles of repetition: motifs, time signatures, time signature pairs, refrains, and melodic-rhythmic phrases. The scale, range, rhythmic and metrical structure, and performance of the songs are also examined.

Bèla Bartòk's disciples and Zoltàn Kodàly (1882-1967), composer, teacher, and ethnomusicologist, continued and refined the classification, which gradually took shape between 1951 and 2011 in the twelve volumes of Magyar Népzene Tára, Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae.

Two major groups of songs were identified:

- Free-structured melodies

- Songs with fixed or strophic structures

(Olsvai, 1998, p. 521)

Observation of the performance context complemented the melodic-rhythmic and metrical analysis of the songs: free-structured melodies are circumstantial. These songs are systematically performed in specific circumstances (important turning points in human life, calendar festivals, children's games, etc.).

Songs with a fixed structure or strophic structure are performed freely on any occasion (Olsvai, 1998). The first five volumes of Magyar Népzene Tára, Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae are devoted to non-circumstantial songs. Starting with the sixth volume, the classification of songs with a fixed or strophic structure began.

In the case of fixed structures, the musical phrases, their relationships, and the final notes of the phrases are compared. Based on the comparative analyses, the major styles (categories) of songs are defined. These categories include the typological classification of songs.

The major categories are the old style, the new style, and a mixed category. In his study, before detailing their characteristics in detail, Imre Olsvai (1931-2014), an ethnomusicologist and educator, briefly presents them.

The characteristics of the old style (Olsvai, 1998, p. 523):

- The return structure does not exist (the first and last musical phrases are not identical; they differ in both content and pitch).

- The melodic line is generally descending (the movements of the first musical phrase are higher than those of the last).

- The pentatonic is perfect or perceptible.

- The number of syllables per verse is small or medium (in the most common types, the number of syllables per verse is 6, 8, and 11; the number of syllables never exceeds 15).

- At the beginning of the century, at the time of collection, researchers frequently noted that these songs were performed by elderly people. Young people almost never sang them. The performance style of the elderly was the most distant from the performance of urban folk melodies by city dwellers.

Characteristics of the new style (Olsvai, 1998, p. 524):

- The melodic content and pitch of the first and last musical phrases are identical (return structure).

- The third musical phrase is always different from the first and fourth musical phrases.

- If the structure of the first two musical phrases is A, B… or A, A, the third musical phrase is always B; this phrase cannot be A5 or A3. (The superscript number indicates that the phrase A is transposed up a fifth or a third.)

- In the early 20th century, songs in this style were the deliberate musical expression of young people; older people rarely sang them.

Characteristics of the Mixed Category:

According to Olsvai (1998, p. 525), songs classified in the mixed category are extremely varied in terms of their musical, rhythmic, and metrical characteristics, as well as their provenance and origins: the Ugric heritage, the influence of written music, or the music of neighboring peoples.

A Question of Learning and Transmission

Between Orality and Writing: Problems of Transcription

Fújnak a fellegek, sung poetry from the oral tradition, was published in the first volume of a method for learning Hungarian singing from the oral tradition : Paksa, Katalin, and Klàra Bodza. 1997. Magyar nèpi ènekiskola. Magyar Nèpművelèsi Intèzet Néptàncosok Szakmai Hàza. Vol. 1. 4 vols. Budapest, p. 171, no. 130.

Accompanied by audio recordings, the four volumes of this collection contain transcriptions of the melodies and lyrics. For learning, the authors propose two complementary approaches: listening to music and/or reading the scores.

Indeed, singing does not resonate in the same way when heard and transcribed. The transition from oral to written form results in the loss of certain information-bearing elements: the timbre of the voice, the intonation of the pitch, the accent, the stress, the rhythm, and the speed. Transcription does not reflect the subtlety of the interpretation, the aesthetic emotions, or the parlando or rubato character of the performance.

According to the authors, the score of the songs is secondary but can nevertheless aid intentional learning because it draws attention to the song's structure (a strophic song comprising four melodic phrases), the ornamentations, and the rhythmic and melodic variations from one stanza to the next that occur during the performance of the song. Transcription can offer an analytical approach to singing.

For ethnomusicologists, transcription constitutes the first step in analysis: the transcriber's perception, musicological, linguistic, and cultural knowledge, are brought into play when listening to and understanding oral musical discourses, as well as during their encoding into writing.

Before learning to sing, several listening sessions can be conducted. The objectives of these listening sessions may concern the melodic-rhythmic structure, the characteristics of the scale, the particularities of the interpretation, the pronunciation of the words, the intonation of the third but also aesthetic emotions.

Listening and Practice

Text and Lyrics

Reading the text can make learning to speak difficult, as the pronunciation of the Hungarian vowel and consonant signs does not always correspond to the pronunciation of French vowels and consonants.

To practice the pronunciation of the words, I suggest recording the spoken word alone:

Lyrics of the song "Fùjnak a Fellegek." Courtesy of the Archives of the Hungarian Institute of Musicology.

For further information, here are other versions and other pieces to listen to:

Variability is one of the essential characteristics of singing in the oral tradition: there are several interpretations, and it changes from one performance to the next. Consequently, a recorded and/or transcribed version is not representative.

The study of a version is the analysis of a current production. To describe the oral tradition songs of a territory, comparative examinations of their multiple realizations are essential. Analyses must be conducted from a synchronic perspective (description of musical dialects, analysis of the relationships between music and gestures, observation of the transmission and use of song, etc.) and a diachronic perspective (influence of written music on oral tradition music, relationship with the oral tradition music of neighboring peoples, examination from a philological perspective, etc.).

To delve deeper, listening to the vocal music of Transdanubia is recommended, particularly that of Somogy County: songs performed a cappella, parlando/rubato performances, ornamentation, the subtleties of interpretation, and the intonation of the neutral third.

A better understanding of the ancient style of Hungarian oral tradition songs is also recommended to understand the different types and diverse interpretations.

Second version, by the same singer, of the song Fùjnak a fellegek:

Fújnak a föllegek, second version

Archive number: 4327e

Incipit: Fújnak a föllegek

Name of performer: Szakáll Józsefné “Miklós” Bebők Judit “Dávid” born 1900

Recording by Imre Olsvai

Registered: 03/07/1962. in Nemespátró – Somogy committee – Transdanubia (western Hungary)

URL: http://db.zti.hu/24ora/mp3/4327e.mp3

Below is the transcription, taken from BARTÒK Bèla and Zoltàn KODÀLY (1973) Magyar Népzene Tàra. Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae. (P. Jàrdànyi & I. Olsvai, Eds.; Vol. 6). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadò, p. 368-369, n°416.

Another performance by Màrta Sebestyèn:

Sebestyèn Màrta, Muzsikàs, Dùdoltam èn Sebestyèn Màrta, CD, Gong-HCD-18118, Hungary, 1993.

http://m.zeneszoveg.hu/m_dalszoveg/34882/muzsikas-egyuttes/fujnak-a-fellegek-zeneszoveg.html

Màrta Sebestyèn also taught this song during a workshop in 2015, organized by the Drom association. An excerpt from this transmission project can be found in the video (at minute 0:28):

https://www.drom-kba.eu/Reportage-a-Bekescsaba-Hongrie-2015.html

Some readings in French for further reading:

BARTÒK Bèla, 1956

"Why and How Do We Collect Popular Music?" Szabolcsi (ed.), Bartòk: His Life and Work. Budapest: Corvina: 164-183. Available at: https://www.musicologie.org/Biographies/b/bartok_b.html.

FELFÖLDI, László and István PÁVAI, 2006

"State of Research on Popular Music and Dance." Ethnologie française 36: 261-272. Available at: https://www.cairn.info/journal-ethnologie-francaise-2006-2-page-261.htm.

NICOLAS François, 2013

"The Logical Issues of Musical Writing and Its Current Changes." Changes in Writing [online]. Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.psorbonne.1750

Nyeki-Korosy, Maria, 2006

"Modern Musical Ethnology: Contexts of an Emergence." Ethnologie française 36: 249-260. Available at: https://www.cairn.info/revue-ethnologie-francaise-2006-2-page-249.htm.

VARGYAS Lajos, 1969

“Hungarian folklore and Eastern Europe”.Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 11: 449–459.Available at: http://vargyaslajos.hu/docs/1960/57Le_folklore_Hongrois_et_lEurope_de_lEst_1969.pdf.

References used in this study:

BARTÒK Bèla, 1966

Bartòk Bèla összegyûjtött ìràsai. Budapest: Zenemûkiadò Vàllalat.

BARTÒK Bèla and Zoltàn KODÀLY, 1973

Magyar Népzene Tàra. Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae. (P. Jàrdànyi & I. Olsvai, Eds.; Vol. 6).Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadò.

BRÂILOIU Constantin, 1973

Problems of ethnomusicology. Texts collected and prefaced by Gilbert Rouget. Publication placed under the patronage of the French Society of Musicology. Geneva: Minkoff.

JÀRDÀNYI Pàl, 1961

A magyar nèpdaltìpusok. 2 flights. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadò.

OLSVAI Imre, 1998

“Zene.” Voigt (dir.), A magyar folkòr. Budapest: Osiris Kiadò : 505‑539.

OSVAI Imre, 1973

« Introduction », Bartòk et Kodàly (dirs.), Magyar Népzene Tàra. Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae. Budapest : Akadémiai Kiadò : 11‑30.

ORTUTAY (dir.), 1977-1981

Magyar Nèprajzi Lexiokon. 4 vols. Budapest : Akadémiai Kiadò.

PAKSA Katalin et Klàra BODZA, 1997

Magyar nèpi ènekiskola. Budapest : Magyar Nèpművelèsi Intèzet Néptàncosok Szakmai Hàza.

SEBÔ Ferenc, 1997

Népzenei Olvasòkönyv. troisième édition. Budapest, Hongrie : Planètàs. Jelenlvô mùlt.

VARGYAS Lajos, 1991

A magyarsàg nèpzenèje. Budapest, Hongrie : Zenemûkiadò Vàllalat.

VARGYAS Lajos, 2006

A magyarsàg nèpzenèja. Budapest, Hongrie : Mezôgazda Kiadò.

VARGYAS Lajos, 1988

« Lìrai népköltèszt ». Vargyas (dir.), Magyar nèprjaz V. Népköltèszet. Budapest : Akadémiai Kiadò : 427‑565.

VIKÀR Bèla,1901

« Èlô nyelvemlèkek ». Ethnographia (11) : 131‑142.