Bulgarie

Taksim Suite

-

Genre :Party music

-

Tradition :Davul-zurna, Balkan music

-

Piece name:Suite Taksims

-

Specifics:Multiple modes (Eviç - Kürdi - Saba - Nikriz - Indian Pentatonic - Hidjaz - Mixolydian)

Songs and dances from Bulgaria and Turkey.

Suite : Taksims, Çalın Davulları, Bir Ayrılık Bir Yoksulluk Bir Ölüm, Indiski Kiuchek, Gaydarsko Horo

Performance of a suite of zurna pieces by Samir Kurtov.

Recorded on August 10, 2020 in Kavrakirovo, Bulgaria © Drom

Folk Music and Modality in Bulgaria and the Balkans

In the Balkans, and particularly in Bulgaria, folk repertoires, often perceived as a form of artistic syncretism, are an agglomeration of several musical concepts.

Three different aesthetics can be heard more or less simultaneously:

- Regional styles involving melodic forms and particular modes generated by ancient and local instruments—the gaïda (a type of bagpipe), various flutes including the kaval (an oblique flute), and the zurna.

- Ottoman and Byzantine music, music with unequal temperament based on the superimposition of tetrachords and pentachords, which form a system of modes called “makam” in Ottoman music and “dromos” in Byzantine music.

- Western music, in its general, stereotypical sense (classical music, jazz, etc.), includes tonal forms, classical harmony, chromaticism, and so on.

Bulgarian music theory, as taught in academies for over fifty years, borrows the system of superimposed tetrachords from Ottoman music. However, according to this teaching, the temperament is equal. Furthermore, local modes, which do not exist in the Ottoman repertoire, are named using the modal vocabulary employed by Western classical music (Dorian, Phrygian, Mixolydian modes, etc.).

The fact that the Bulgarian academic approach does not take microtonality into account does not mean that the music found in Bulgaria is in equal temperament. Indeed, a general movement of "Westernization" and "adjustment" of Bulgarian music and other Balkan music likely took place starting in the late 19th century.

Although their music is largely based on the Ottoman maqam system, Bulgarian musicians very rarely use the corresponding terminology. In fact, only the "Hijaz" maqam is named as such. This is probably due to the fact that this mode is overused in this geographical area.

The Piece: A Suite of Songs, Dances, and Improvisations

This piece is a suite of songs, dances, and taksims (improvisations) in various modes, recorded in Kavrakirovo in August 2020.

Samir Kurtov presents a spontaneous flow and sequence of movements:

-

Taksims (unmeasured improvisations)

-

Çalın Davulları ("Play the davuls," Turkish song)

-

Bir Ayrılık Bir Yoksulluk Bir Ölüm ("A Separation, a Misery, a Death," Turkish song)

-

Indiski kiuchek (Gypsy dance in the Indian style)

-

Gaydarsko horo ("Gaida Player's Round")

Professional musicians in Bulgaria are often called upon to perform at community events for entire days. This is why they are experienced in the art of transitions and can produce long improvisations and endless variations.

Here, the pieces presented come from western Turkey, the Bulgarian Gypsy repertoire, and Bulgarian Thracian music.

As we can see, the repertoire of musicians in the Balkans is not necessarily "regionalized"; it depends on the context. In this video, Samir decides to perform these pieces for his own enjoyment while showcasing his talent.

We chose to present and analyze this suite because Samir demonstrates his many abilities.

Samir is accompanied here by Demir Kurtov, Ognian Fetov, and Martin Dimitrov:

- Demir Kurtov also plays the zurna. Demir was born in 1999 and lives in Kavrakirovo. He is Samir Kurtov's nephew and is learning the zurna from him.

- Ognian Fetov also plays the zurna. Ognian was born and lives in Kavrakirovo. He regularly plays alongside Samir Kurtov on the tapan or the zurna.

- Martin Dimitrov plays the tapan. Martin was born in 1985 and lives in Kavrakirovo. He has played the tapan since he was young, playing for his father, a folk dancer, or to accompany Samir Kurtov..

Samir Kurtov seamlessly blends themes, variations, taksims (unmeasured improvisations), and rhythmic improvisations while exploring numerous modes. The aim is to create movement and playfulness to captivate his audience.

The structure is therefore improvised, and the other musicians must follow the soloist's intentions.

Unlike other styles, there are no pre-established rules regarding modulations, transitions, and possible developments. The only constraints are musical effectiveness and the technical limitations of the instrument—which Samir readily transcends.

Listening to and analyzing Samir Kurtov's suite: Ottoman music and temperament in the Balkans

To analyze Samir Kurtov's suite as precisely as possible, I draw upon theoretical concepts and notational systems from both Ottoman and Western classical music. I provide further explanations to facilitate understanding of Ottoman theory. I also explain the workings of temperament in Balkan music.

The Structure of the Suite

The suite performed by Samir Kurtov and his companions is composed of four distinct themes:

- Çalın Davulları - Turkish song

- Bir Ayrılık Bir Yoksulluk Bir Ölüm - Turkish song

- Indiski Kiuchek

- Gaydarsko Horo

and improvisations in two types of forms:

- the taksim, an unmeasured form in the "alaturka" style

- rhythmic improvisation in the Bulgarian style.

Modal Structure of the Samir Kurtov Suite

1 - Taksim (unmeasured improvisation) in the Segah makam

2 - Çalın Davulları (Songs of the Day)

3 - Bir Ayrılık Bir Yoksulluk Bir Ölüm (Bir Ayrılık, Bir Yoksulluk, Bir Ölüm)

4 - Taksim in the Saba makam, then in the Nikriz makam

5 - Indiski Kiuchek (Indian-style Gypsy dance), improvisations and variations

6 - Modulation in the Hijaz makam a fourth higher

7 - Gaydarsko Horo (Gaida Player's Round)

8 - Rhythmic improvisation

9 - Modulation a tone lower in the Nikriz makam

10 - Modulation a tone higher, return to the Gaydarsko Horo

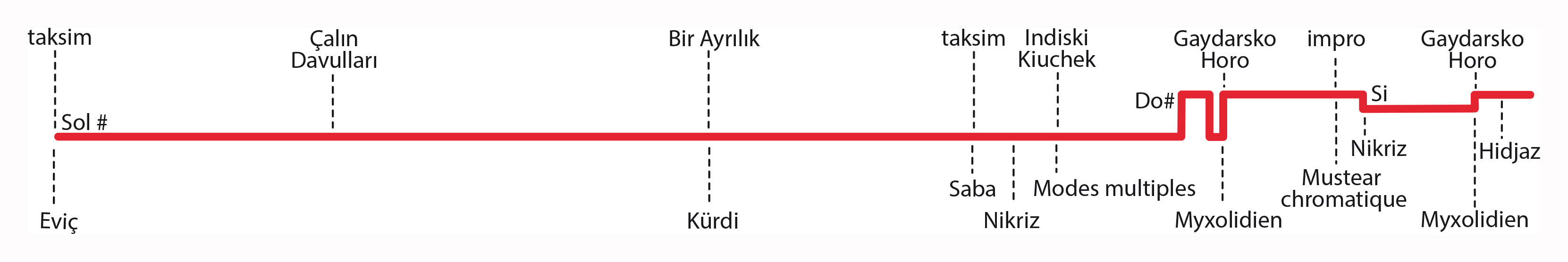

The following diagram is a timeline representing the development of the suite.

The red line corresponds to the drone of the accompanying zurnas. Above this are indicated the themes and improvisations, and below them the modes played.

It can be observed that the narrative form of this suite resembles a crescendo. Indeed, the closer one gets to the end, the more events occur:

- the themes and improvisations alternate more and more rapidly;

- the different modes accumulate towards the end;

- the drone changes several times, but only in the final section;

- the tempo accelerates exponentially;

- the improvisations played at the beginning are taksim, that is, unmeasured improvisations leaving space, then, as one approaches the end, they become rhythmic, fast, and tightly focused.

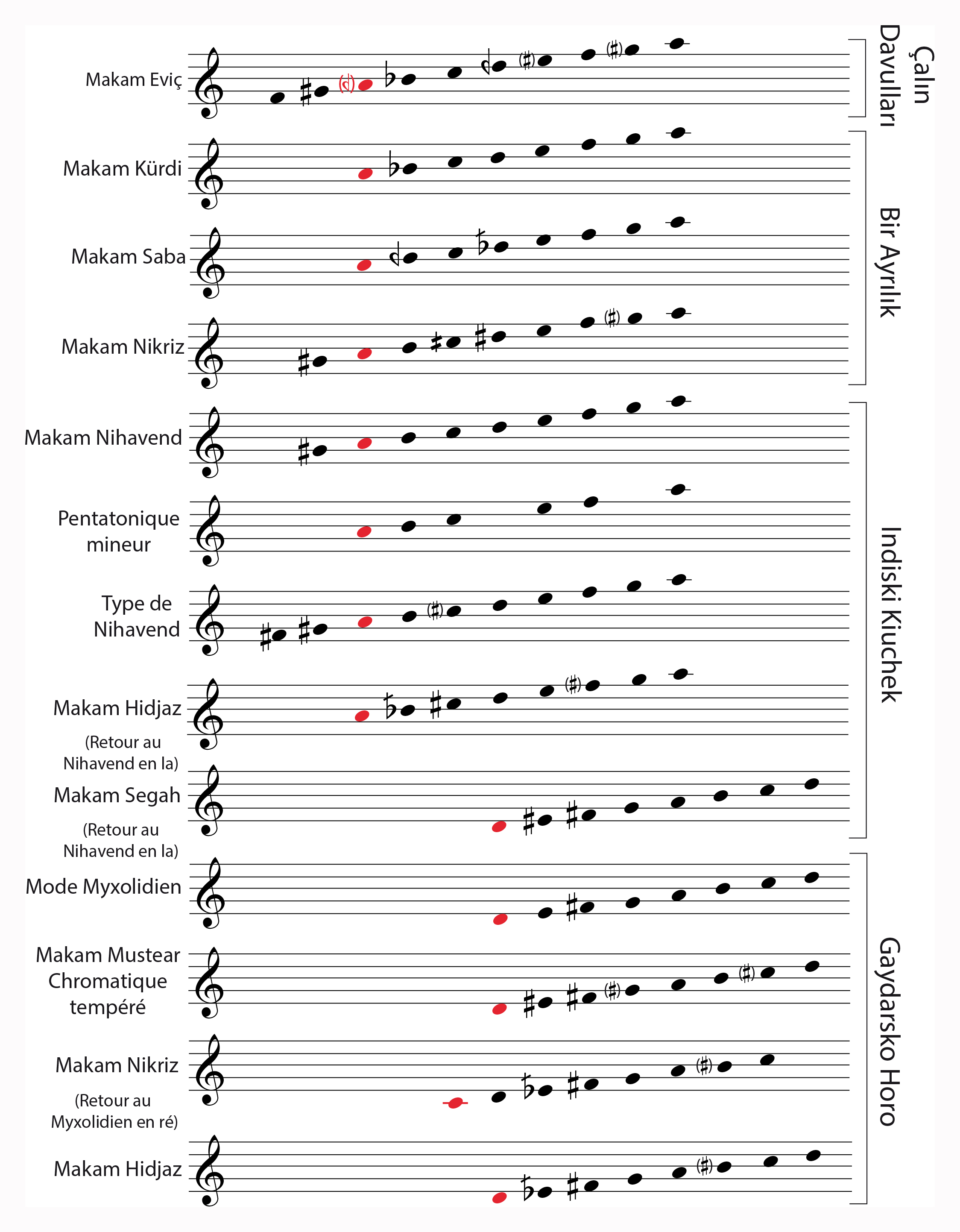

The modes used in the suite

Since Balkan music has both an Eastern and Western approach to modes, these can be understood using the systems of unequal or equal temperament . For this reason, the transcription of the modes played in this suite is a blend of Ottoman and Western classical notation. When it is a makam, I use the Ottoman system, and when it is another type of mode, I use equal temperament notation.

The degrees in red correspond to the drone of the accompanying zurnas, and the accidentals in parentheses indicate that they are accidental or not necessarily played.

The modes are arranged in the order in which they appear. I chose A as the starting tonic for readability, but Samir's original version is in G#.

Samir's diverse influences mean that we hear modes from various musical backgrounds.

For example, in the Indiski kiuchek, Samir moves from the Nihavend makam to a pentatonic scale inspired by Indian music. He then returns to Nihavend, to which he succinctly adds a major third and a major sixth (in the lower section) to reproduce the sound of certain Indian modes. He then briefly mentions the Hidjaz makam and moves on to the Segah makam.

He thus alternates between Ottoman and Indian musical vocabularies.

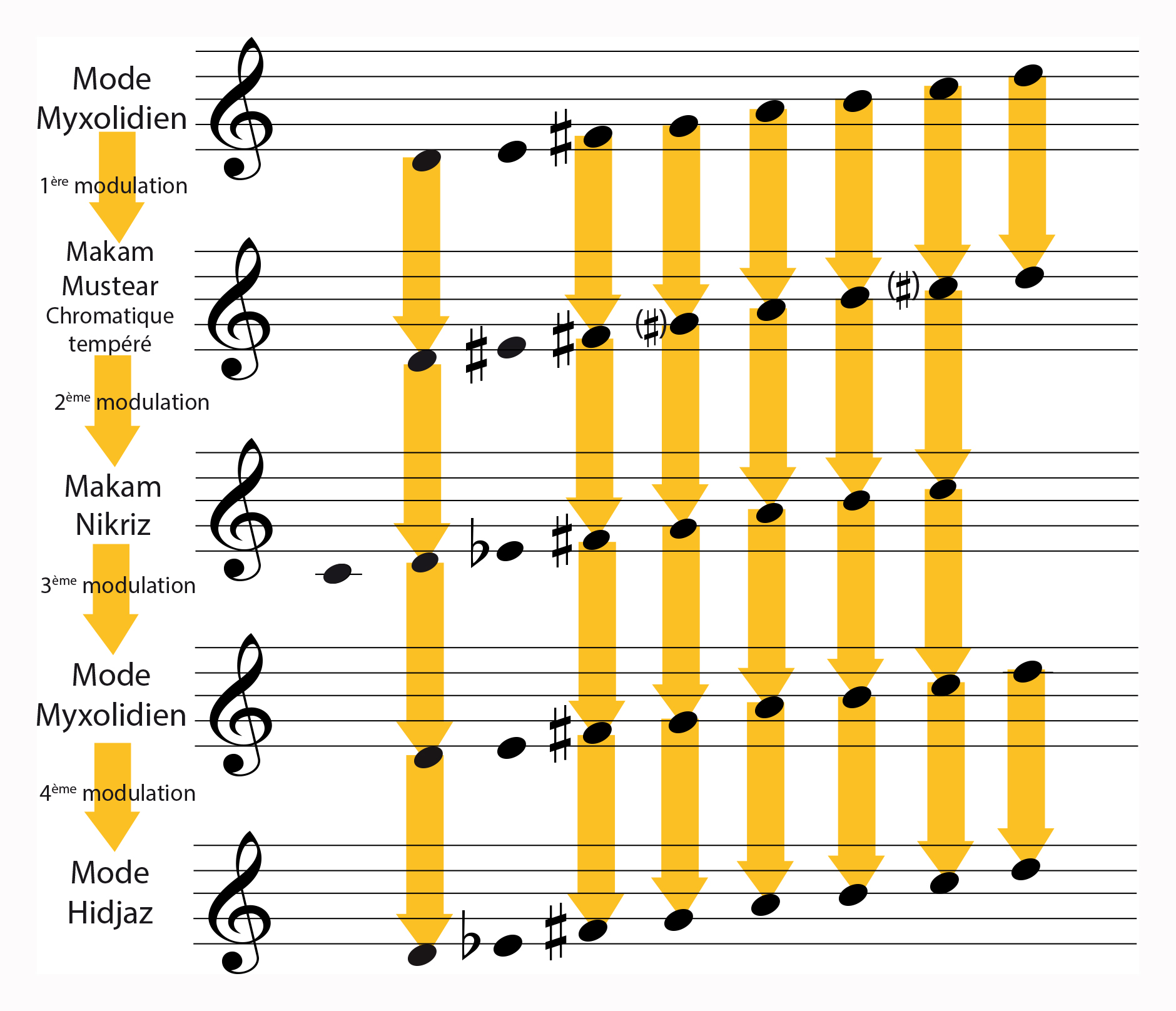

Some examples of modulations in Samir Kurtov's suite:

In the last section, "Gaydarsko Horo," Samir performs four modulations.

With each modulation, he shifts only one degree, always the second—or the third for the Nikriz makam, since it descends a whole tone.

The Müstear makam is a mode widely used in Balkan music. However, it is played in a tempered manner and often with the addition of chromaticism between the third and fourth and between the sixth and seventh.

A Closer Look at a Piece from the Suite: Çalın Davulları, a Stylistic Exercise

“Çalın Davulları - Selanik Türküsü” (“Play the Drums!” - “Song of Thessaloniki”) is a favorite among Turkish Roma musicians when it comes to showcasing their skills. It is generally performed at a slow tempo or rubato, allowing the musician to fully express themselves through variations, digressions, and modulations. It is with this intention that Samir takes on this theme to demonstrate his virtuoso qualities.

However, to understand and analyze what Samir is playing here, one must be familiar with the sung version, which is easier to grasp and remains the basic structure of this stylistic exercise.

As complex as it may seem, Samir's sinuous embellishments and sudden flights of fancy respect the song's foundational elements.

Vocals: Vaggelis Daskaloudis

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ApUNw45aQ9c

Vocals: Vaggelis Daskaloudis

Zurna: Zissis Chidzos, Grigoris Goras

Davul: M. Madarlis, Yannis Dramalis, V. Zoras

Album: Ellines Akrites - The Guardians of Hellenism Vol.7 Macedonia

Licensed to YouTube by The Orchard Music (on behalf of FM Records)

Another song that evokes the role of the davul is "Ushti Baba, o davulya maren" ("Arise, Grandmother, they are hitting the davul!"). This is a Roma song from North Macedonia, here performed by the Kocani Orkestar:

Usti, Usti Baba / Rumunsko Gazal - Kocani Orkestar

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4wdt3-Caijk&feature=share

Title Usti, Usti Baba/Rumunsko Gazal · Kocani Orkestar

Disc : Alone At My Wedding

℗ 2002 Crammed Discs Released on: 2002-10-01

Producer: Michel Winter Producer: Stephane Karo

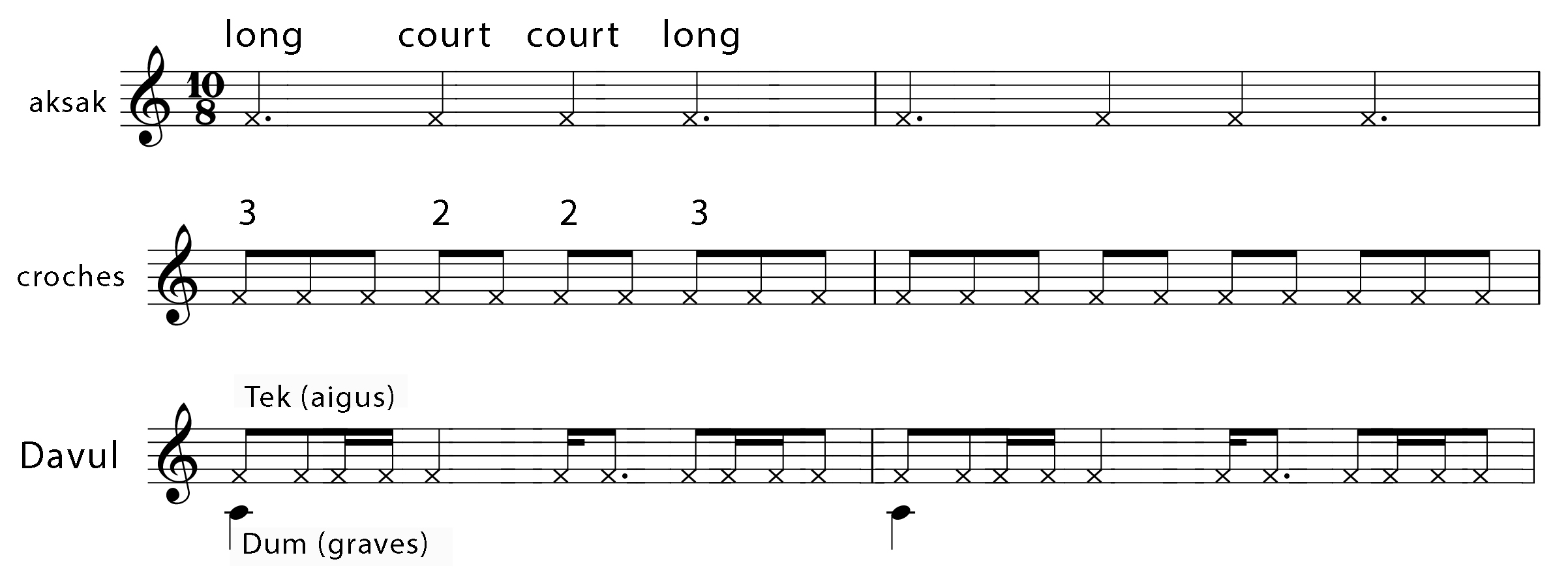

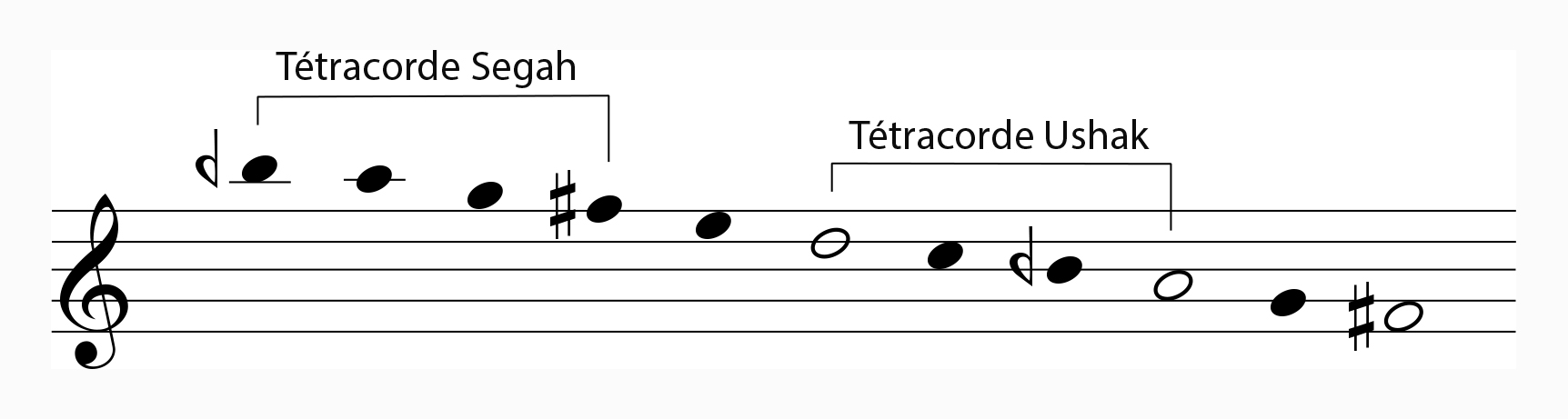

Rythm of Çalın Davulları :

Samir's version here is unmetered and without percussion. This allows him considerable rhythmic freedom and the ability to play long variations without adhering to a specific tempo.

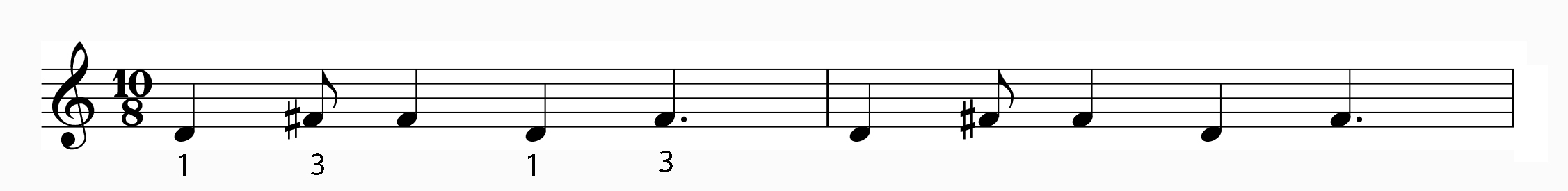

That said, originally, “Çalın Davulları” is a piece in 10/8 time. This rhythm is known as Curcuna in Turkey (djurdjuna), and Jurjīnah in Arabic. Rather rare in the Balkans and western Turkey, it is very common in the Arab-Kurdish regions (Iraq, Syria, and southeastern Turkey).

The ten eighth notes of the measure are distributed as follows: 3 - 2 - 2 - 3.

In the way aksak rhythms are conceived, this translates to: long-short-short-long.

Here is an example of a davul accompaniment to the Curcuna rhythm by a musician from Küçük Hasan, the zurna player whose interpretation Samir drew inspiration from for this piece:

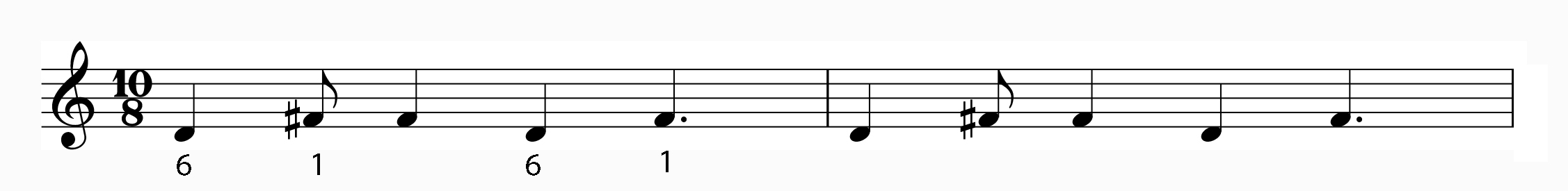

Structure of Çalın Davulları :

Samir's version, although unmetered, follows the structure A B B C B.

The song is usually composed of two melodic cells (A and B) and a refrain (R).

The versions performed by Küçük Hasan (the Turkish zurnadji from whom Samir drew this piece) consist of a purely instrumental section (C) – no lyrics are included.

Based on the numerous existing recordings available online, the arrangement of the sections is not fixed.

In the sung versions, section B can be considered the second part of A and then the refrain. It also functions as an instrumental in the sung versions, which explains its frequent repetition, as in the version sung by Ekrem Düzgünoğlu.

The structure is as follows: RR B RR B RR AB R B RR AB R B

Ekrem Düzgünoğlu, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBm5THRxUCo. Destanlaşan Türküler Album, Vol. 2 - 2005, publisher: muzikplay

As for Küçük Hasan's interpretations, they do not follow the song's structure and are different each time. Here are three different versions:

Version 1 by Kuçuk Hasan - structure : CC RR AB R B RR AB B CCC RR

Version 2 by Kuçuk Hasan - structure : C RR AB CCC

Version 3 by Kuçuk Hasan - structure : CC RR AB B RR - percussion B RR ABB CC

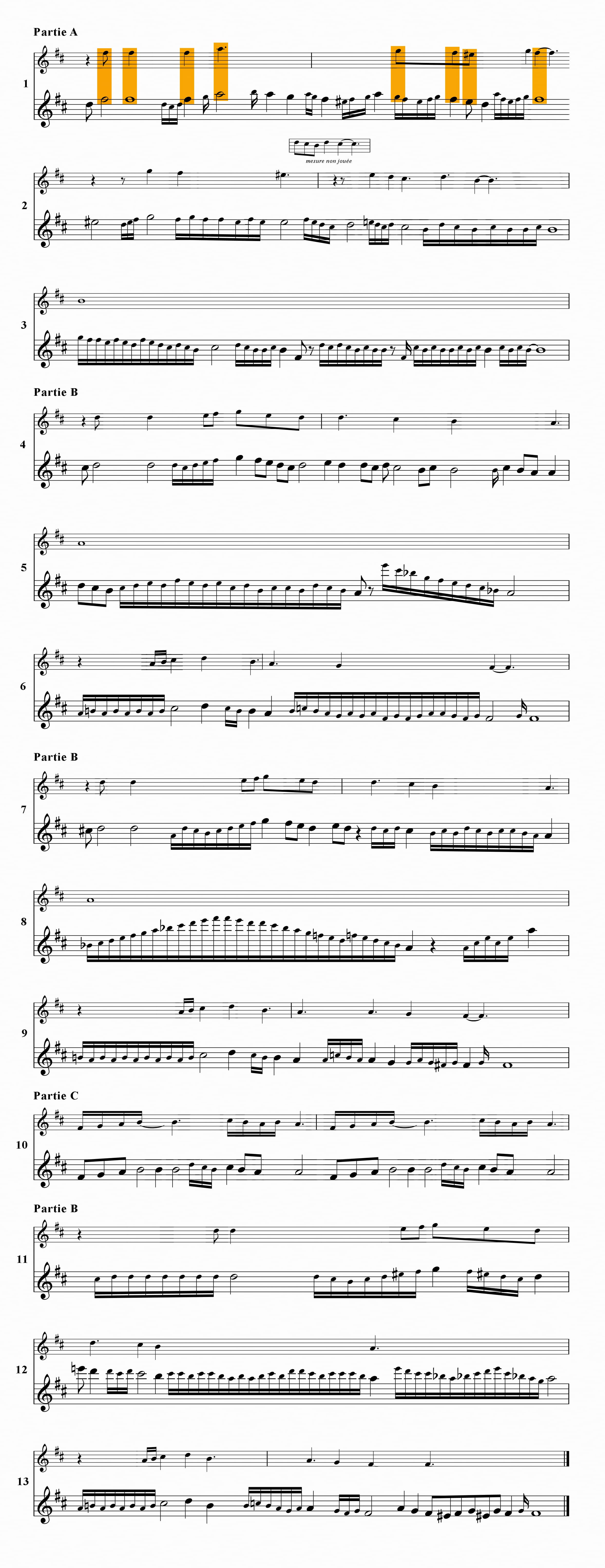

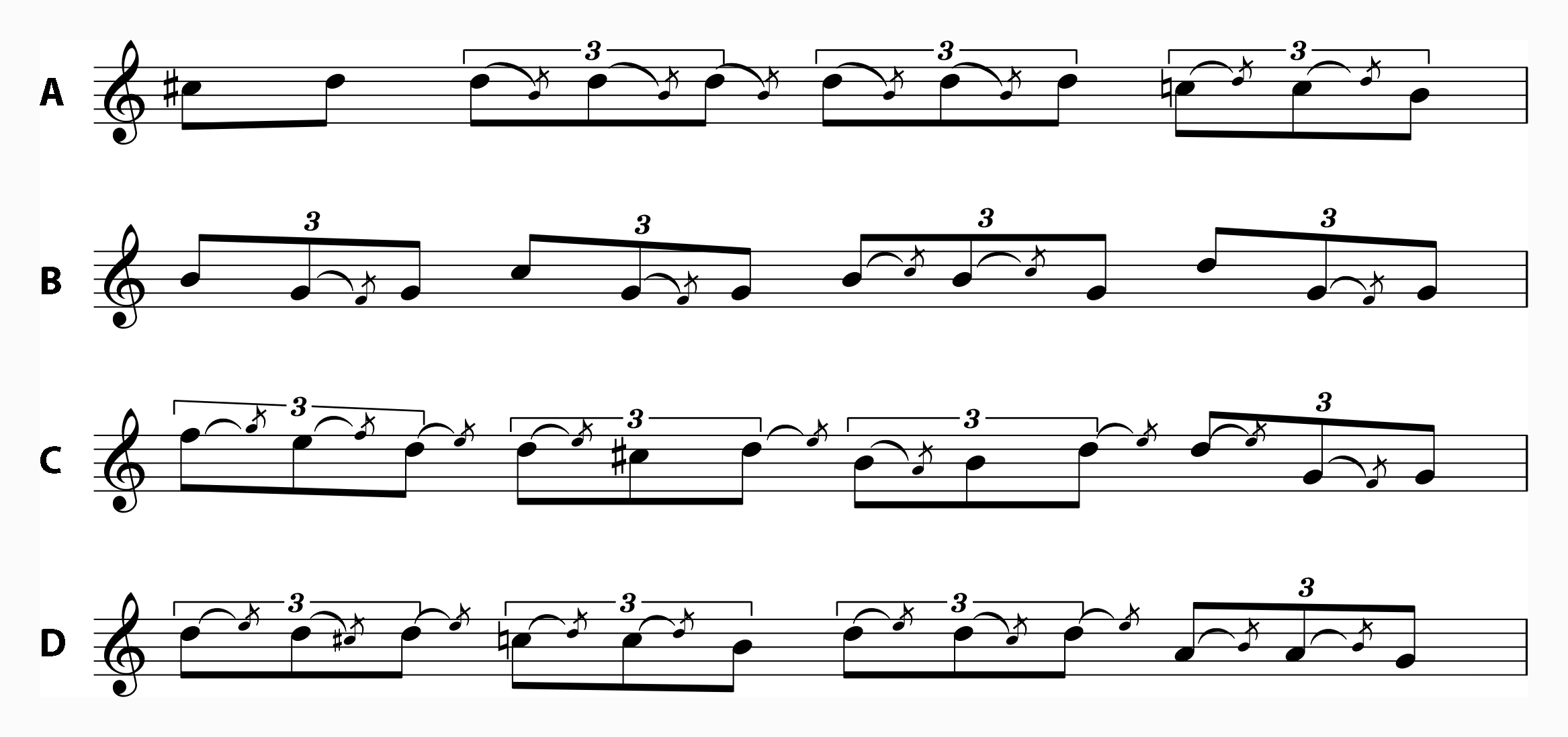

Structure and transcription of "Çalın Davulları" played by Samir Kurtov

The transcription of Samir's interpretation is organized on two lines:

- The first line corresponds to the sung version, simplified here for clarity.

- The second line is the transcription of Samir's phrases. To visually highlight Samir's dynamic playing style, the fast phrases are written as long groups of sixteenth notes. No meter, tempered.

This layout allows us to visualize the relationship between the song and Samir's version. He uses the foundational elements of the original song to structure his musical discourse and to be able to diverge significantly from the theme in long variations while still subtly alluding to it.

This unmeasured—yet structured—interpretation is similar to the construction of a taksim. In the video, if one is unfamiliar with the song “Çalın Davulları,” it is difficult to distinguish the taksim preceding the song from the song itself, as they are performed in the same way.

Note: For clarity, the musical score does not correspond to the key played in the video.

*vidéo séquencée*

Mode of Çalın Davulları: the “Eviç” makam

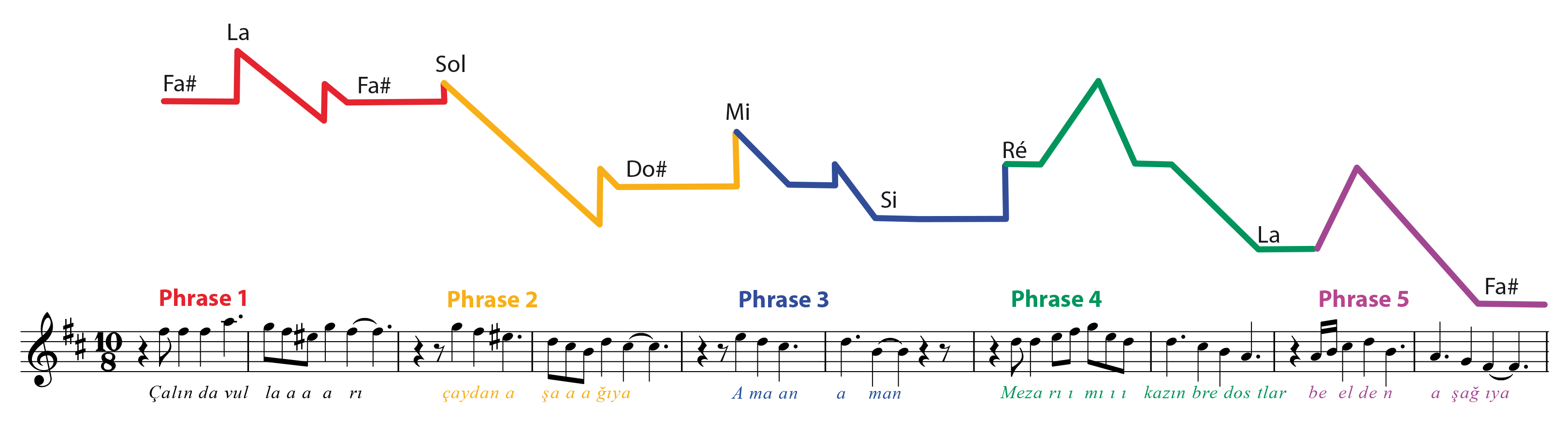

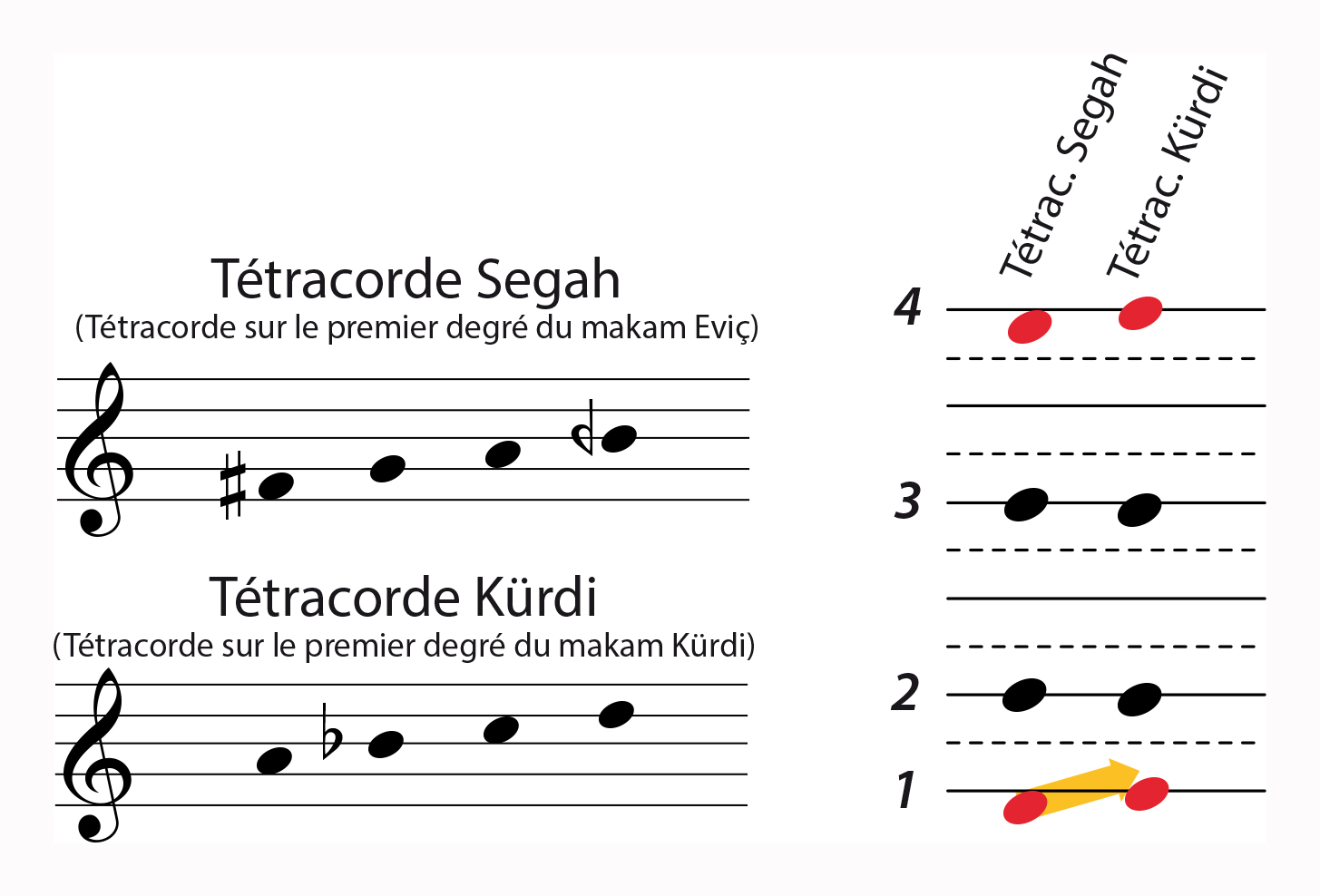

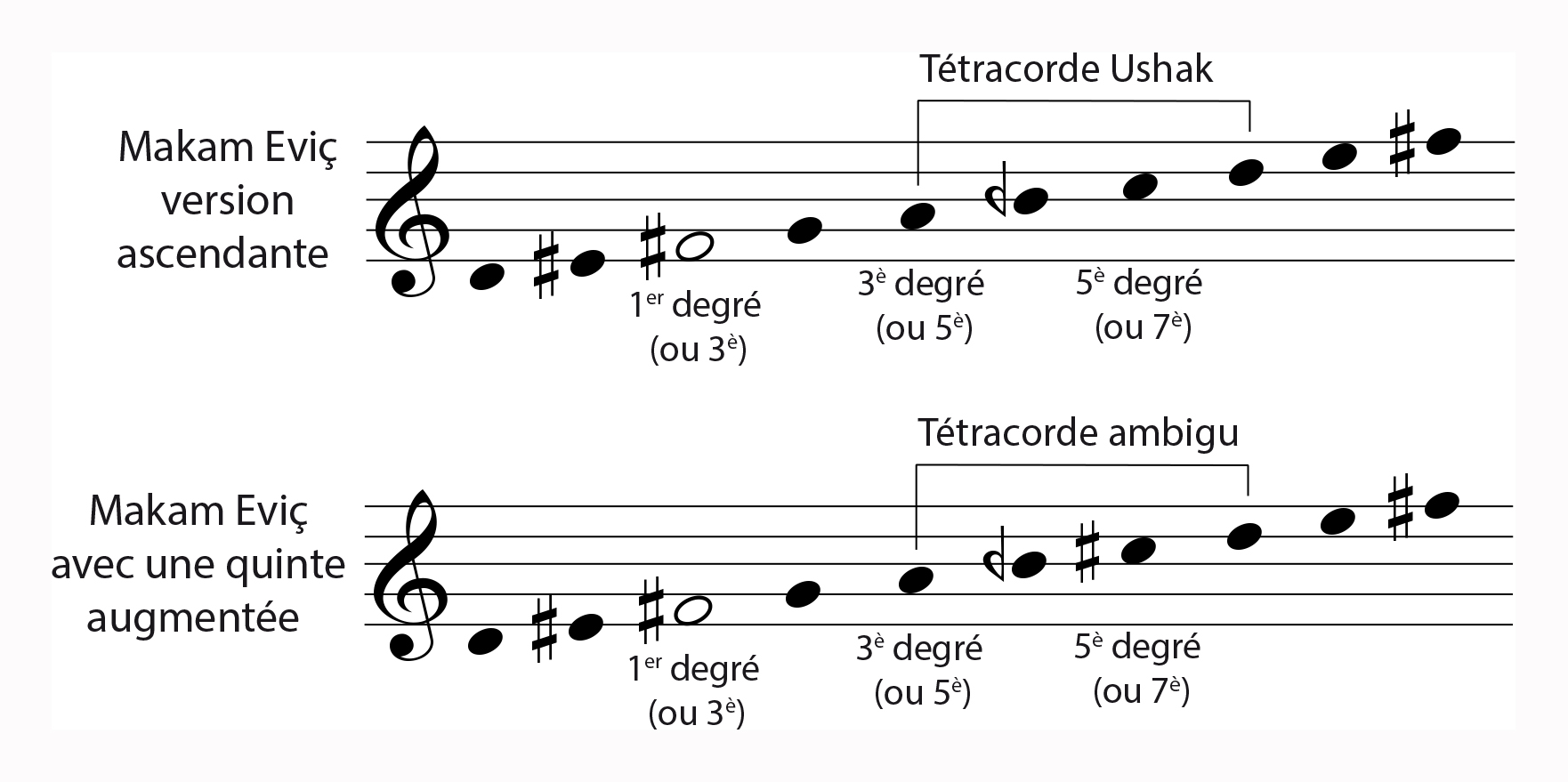

The song “Çalın Davulları” is composed in the makam called “Eviç.” This mode is related to other similar makams such as Segah, Hüzzam, Müstear, and Iraq. All these makams share a common characteristic: they begin with the Segah tetrachord.

The Segah tetrachord is most often notated starting from "B," but for the transcription of "Çalın Davulları," it will be notated starting from F#.

Behavior of the Eviç makam:

The Eviç makam differs from its related makams in its descending behavior. Its melodies, whether improvised or composed, begin in the upper octave and then gradually descend to the lower octave.

Here are two examples in the Eviç makam:

1) Eviç saz semai by Sedat Öztoprak

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-4MoINNBGsc, Nubar Tekyay: violin, Udi Yorgo Bacanos: oud. Archives 663 of Reşit Çağın

2) Zeybek Üç kemerin dibegi, by Mansur Köfeci - clarinet

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e8FQsBEh2K4. Clarinet : Mansur Köfeci

The song “Çalın Davulları” develops on this same principle:

Description of the Eviç makam according to Ottoman music theory

Here is the Eviç makam, as explained in the Ottoman music theory book “Türk Muzikisi Dersleri” (Turkish Music Lessons):

According to this notation, the makam begins on F# an octave higher. This high F# corresponds to the Eviç degree. The “Eviç makam” therefore begins on the Eviç degree.

Here are the annotations given for this mode:

- The tonic is the degree called “Irak” (here, low F# - a comma lower than F# in equal temperament). Note that the names of the degrees are not the same at the octave. The F# at the bottom of the staff is called “Irak,” and the one at the top is called “Eviç.”

- It is a makam with a descending behavior.

- Its strong degree (equivalent to the dominant) is called “Dugah”—here, it is the 3rd degree, which is the note “A.”

- The equivalent of the leading tone is the degree called “Acem Asiran”—here, the 7th degree, which is the note “F natural.”

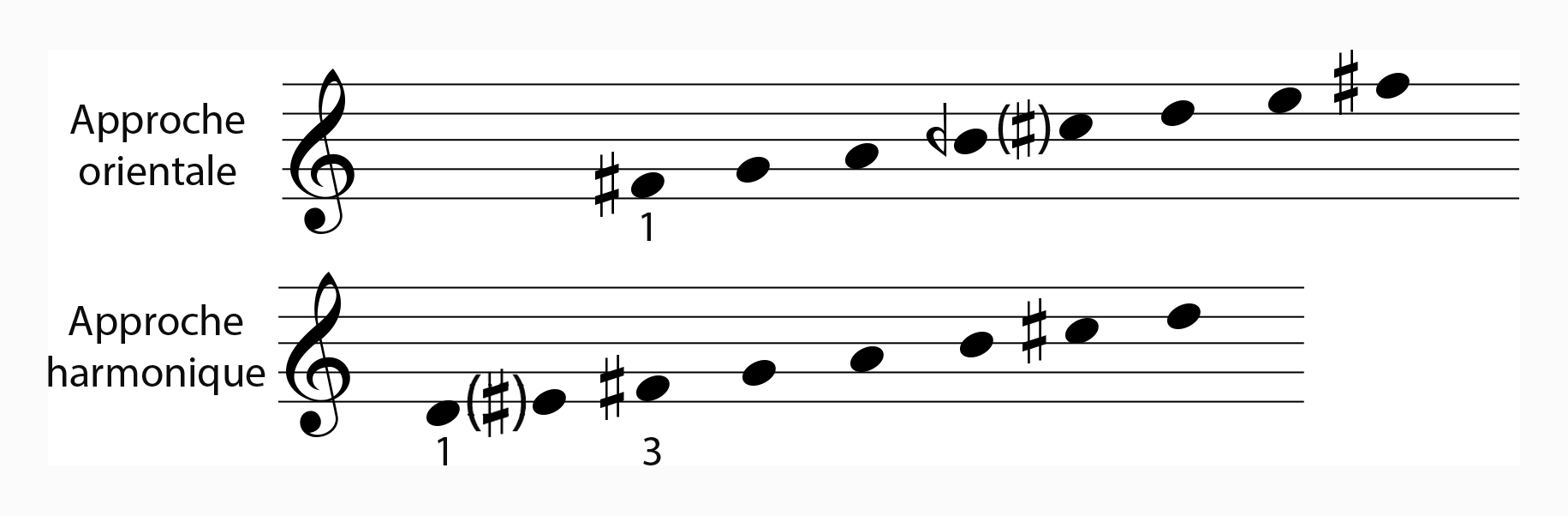

Misunderstandings Regarding the Tonic of the “Eviç” Makam:

According to Ottoman theory, the Eviç makam has its first degree (here F#) which is a comma lower than a tempered tonic.

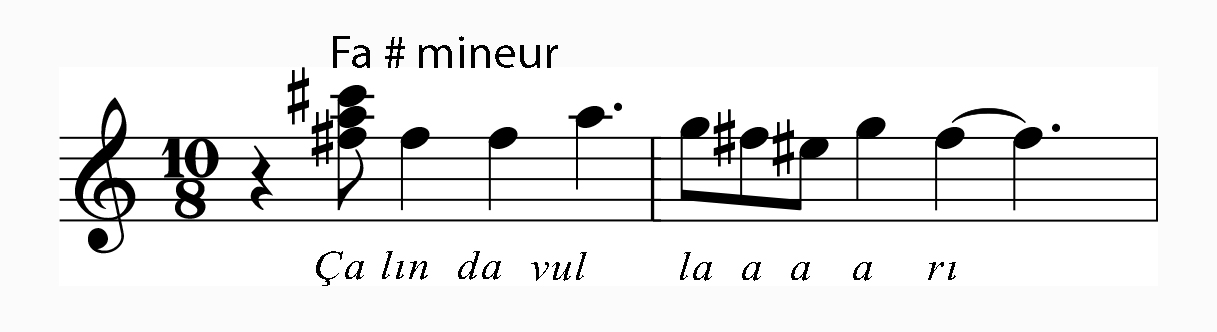

This particular color can be quickly recognized, especially through certain easily identifiable musical motifs. The refrain (R) of “Çalın Davulları” is one such motif:

Refrain of “Çalın Davulları”

If we follow Ottoman theory, these two notes are therefore the 6th and 1st degrees.

However, with a harmonic approach to this refrain, these two notes are rather the 1st and 3rd degrees of the refrain.

For the “Eviç” makam and for all its relatives in the makam family resembling the Segah makam, there is a break between the Eastern and Western approaches.

The problem becomes apparent when it comes to harmonizing these modes.

Here is an example with two harmonized versions of “Çalın Davulları”.

The first considers the first note of the song to be the tonic and harmonizes the first chord in minor from it.

Minor version, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8to6g5ZW0I. Vocals by Ferhat Göçer, album Anadolu Aryaları (1), licensed to YouTube by Videomite Music (on behalf of mmf edisyon).

The second considers the first note of the song to be the major third of the mode and harmonizes the first chord in major.

Major version. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OvhPEgtH6s0 #BuTopraklarınSesleri Vocals & Guitar: Evrencan Gündüz

Vocals & Guitar: Evrencan Gündüz

Bass: Enver Muhamedi

Cajon: Kaan Akıshalı

Cello: Reşad Çiçe

Oud: Selim Boyacı

Violins: Elvan Kızılay, Selen Kesova

Production: Semih Baruh

In the Balkans, the use of harmonic instruments to accompany melodies from the makam family has been practiced for at least a century. Thus, this family of makam is now almost always harmonized in major keys. What is considered the tonic in Eastern music becomes the major third, and parallel melodies are often added to the main melody, starting from the lower third.

To illustrate this evolution, here are two versions of the Macedonian song “Georgi Sugarev,” which originated in the makam segah.

The older version respects the temperament of the makam:

"Georgi Sugarev," by Hristo Arsov & Karlo Orchestra - 1930s

Hristo Arsov & Karlo Orchestra - 1930s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NycsmBDVDVg&ab_channel=KarloOrchestra-Topic

Album: Song Of The Crooked Dance Early Bulgarian Traditional

℗ Yazoo, released on: 2005-06-20, concédé à youtube par Entertainment One Distribution US.

As for the modern tempered version, it is harmonized in major and adds a melody a third lower:

"Zaplakalo e Mariovo", by Petranka Kostadinova, 1999. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9LqTGTm-LxI. Album: Macedonian Folk Songs, licensed to YouTube by The Orchard Music (on behalf of Mister Company) and a music rights management company

The Eviç mode in the song “Çalın Davulları” and transcription issues

This is why we find two possible key signatures for this piece:

- The key signature usually used for the Eviç makam, so seeing it tells us that we are in the makam system with unequal temperament and that the first degree is a slightly low F#. The C# does not appear in the key signature but is notated here as an accidental.

- Or with the D major key signature – two sharps in the clef, F# and C# – and we are apparently in a tempered mode.

Unlike Ottoman classical music, Turkish folk music (of which “Çalın Davulları” is a part) is often less rigorous in its transcriptions. Thus, untempered alterations are not necessarily notated, and one might think, upon reading a transcription of “Çalın Davulları,” that one is dealing with a simple major mode. In general, musicians have already internalized the intonations specific to Turkish music, and in this particular situation, even with an inaccurate key signature, they will still respect the unequal temperament of the Eviç makam.

The “Eviç” mode by Samir Kurtov

During the taksim introducing “Çalın Davulları,” Samir does not adhere to the descending pattern of the Eviç makam. He begins with the bass note, then ascends to the octave before descending again. This melodic form more closely resembles the behavior of the Segah makam. This is because, unlike in Turkey, the theoretical framework of Ottoman music does not exist in the Balkans today, and consequently, the question of whether or not to adhere to the rules of a makam is not really relevant. After all, the Eviç and Segah makams are very similar and are essentially the same if one is unfamiliar with the rules of Ottoman music.

Taksim, by Samir Kurtov © Drom 2020

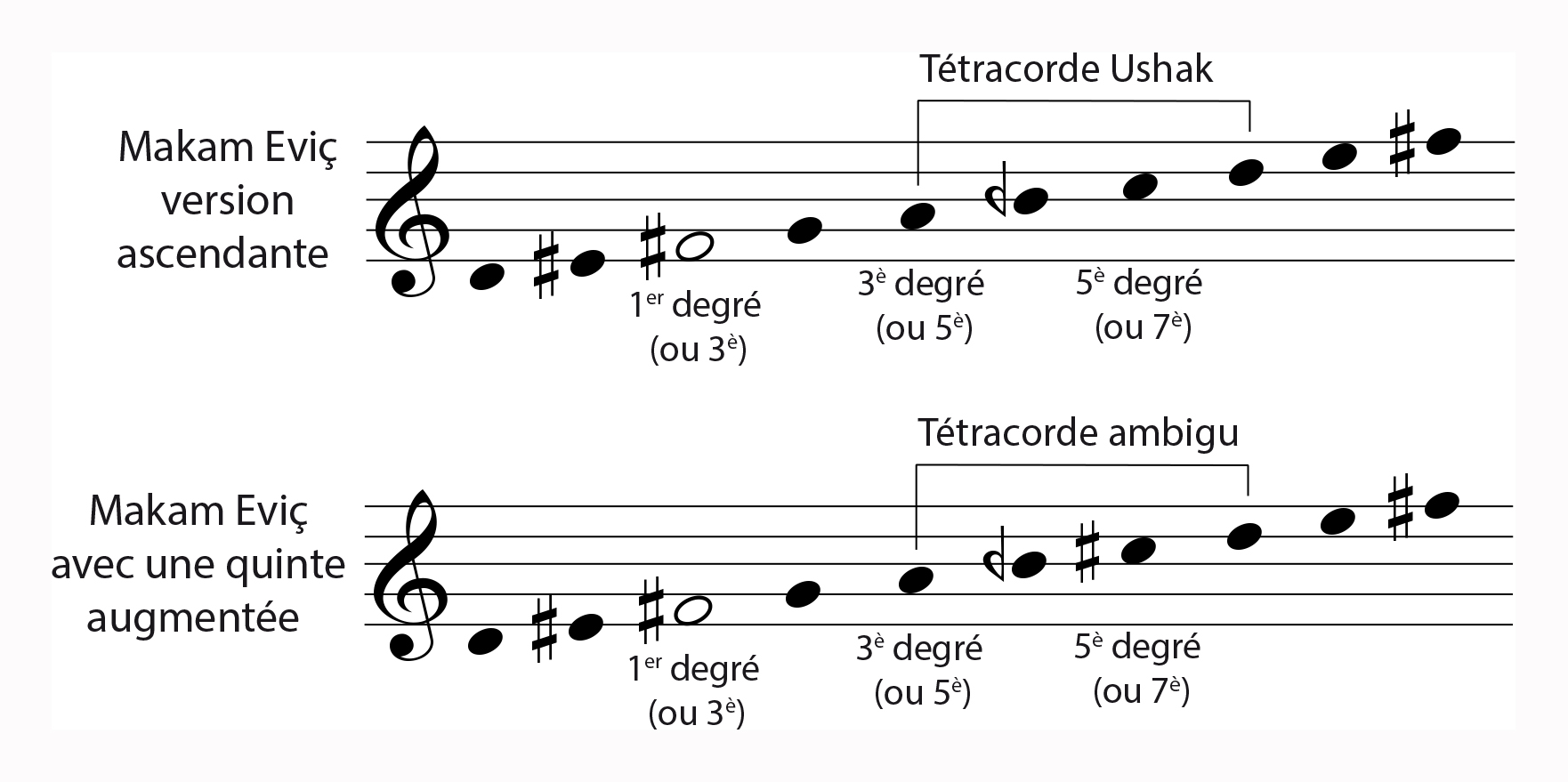

The Ambiguity Among the Eviç Family Makams

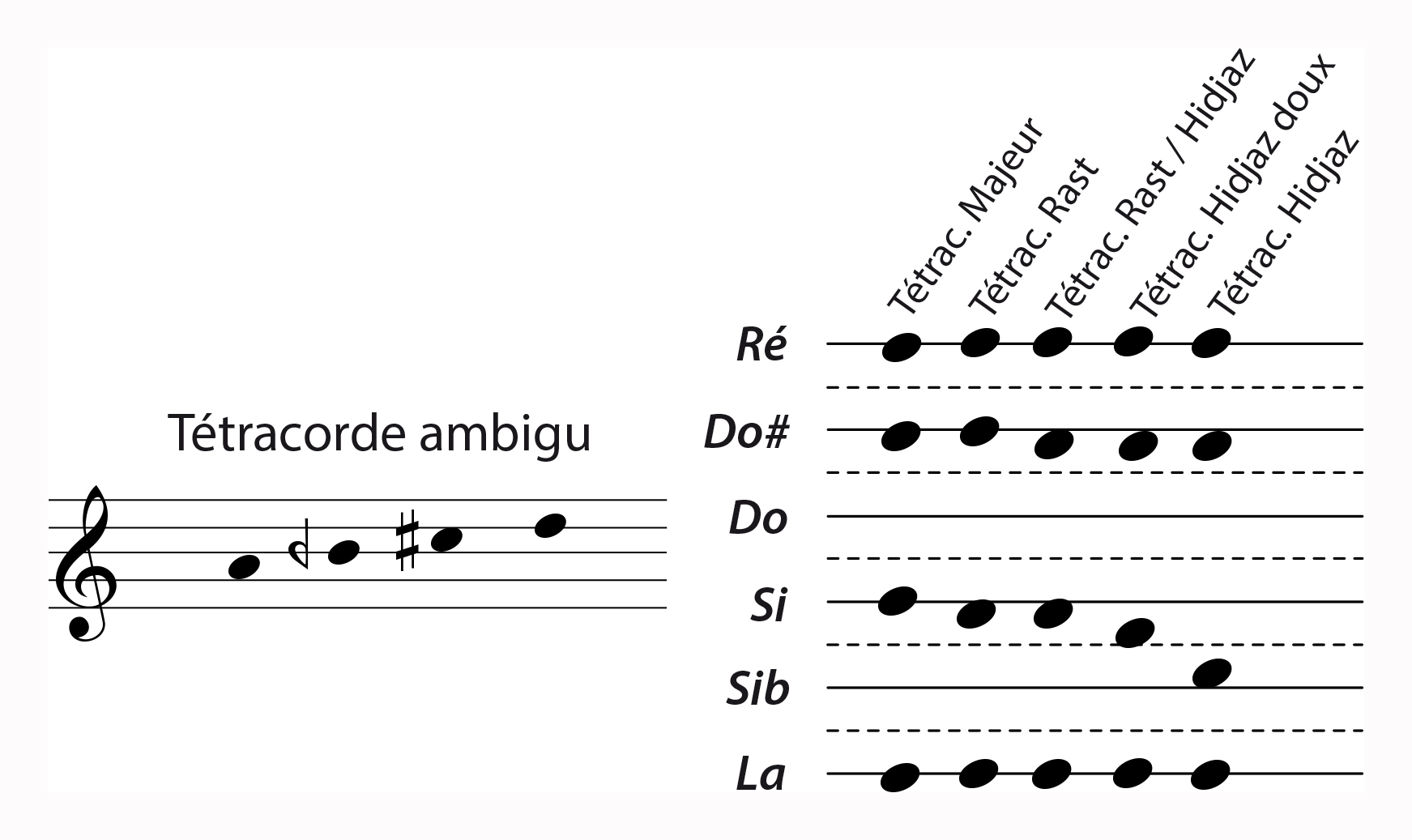

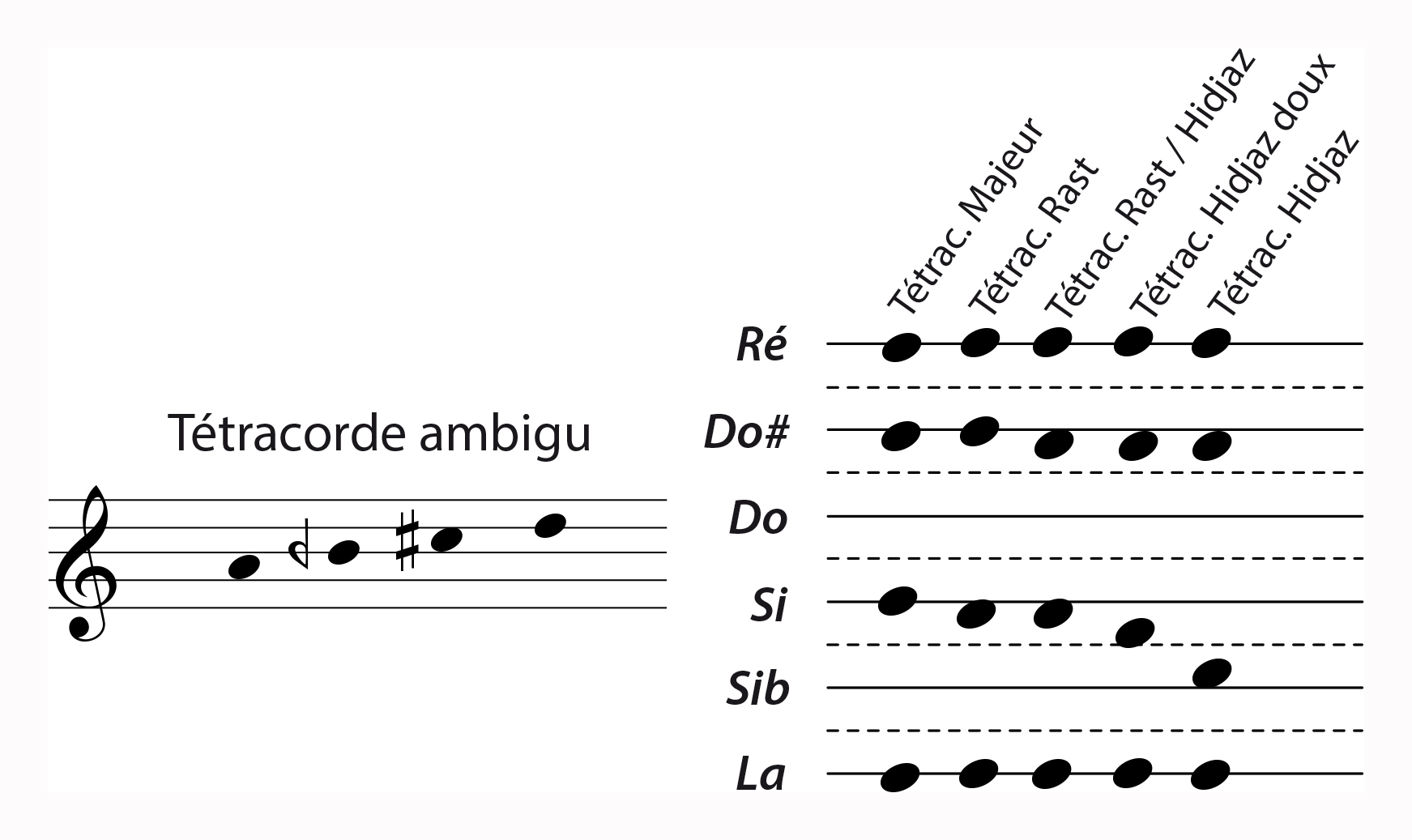

In the Eviç family makams, the tetrachord beginning on the 3rd degree can be confusing. In the version of the Eviç makam proposed by Ottoman theory, the 5th degree is a perfect chord (C), so we consider that from the 3rd degree onward, we have the Ushak tetrachord. In the Eviç makam version of “Çalın Davulları,” the 5th degree is augmented (C#), so the Ushak tetrachord disappears and is replaced by a tetrachord that can be interpreted and tuned in various ways.

The Ambiguity Between Tetrachords, by Laurent Clouet. © Laurent Clouet - Drom 2021

The Temperament of the Drone

Contrary to Ottoman theory, in this video the first degree of the mode (which is also the drone played by the zurnas) is tempered. This allows Samir to modulate in the Kürdi makam for the following piece, “Bir Ayrılık Bir Yoksulluk Bir Ölüm,” which, once again, is not very conventional from the perspective of Ottoman music.

Indeed, if the tonic were the original tonic of the Eviç makam (that is, a degree slightly lower than a tempered degree), it would have to rise by a comma to move from the Eviç makam to the Kürdi makam.

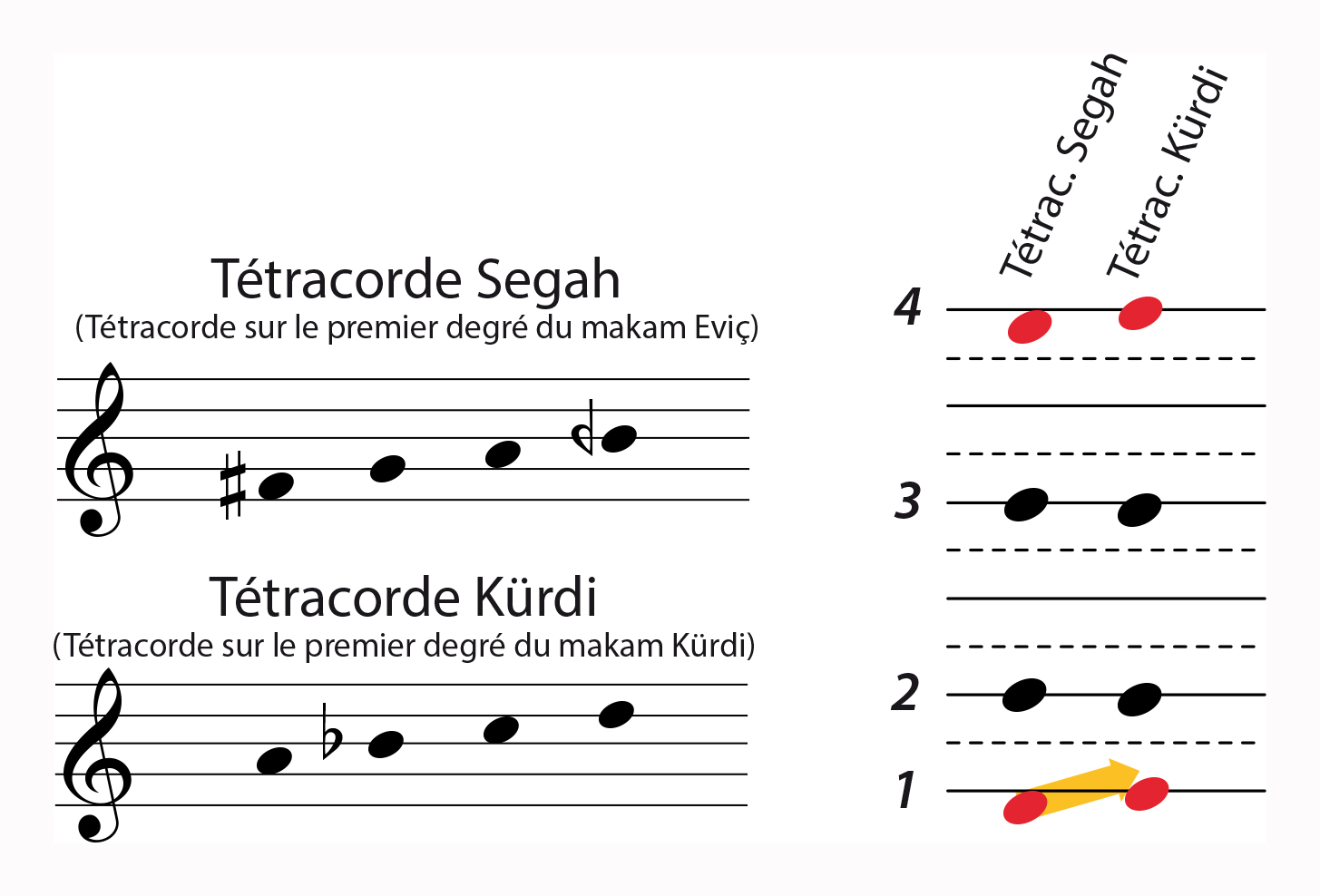

The untempered Segah and Kürdi tetrachords

Here, the Kürdi tetrachord is notated on the staff starting from A, as is the custom in Ottoman music, but the tetrachord scales remain parallel in the diagram to illustrate the differences between the two tetrachords.

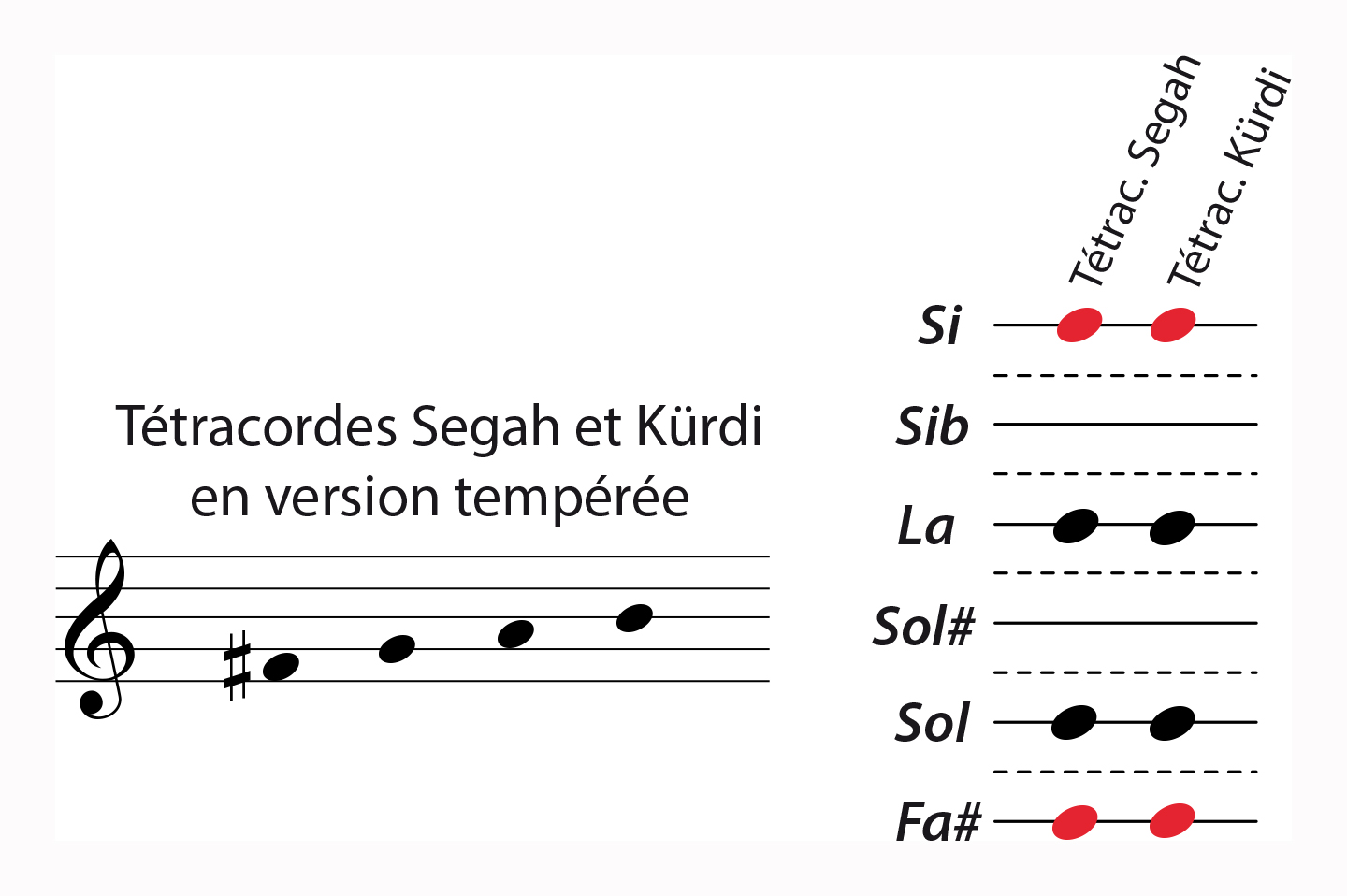

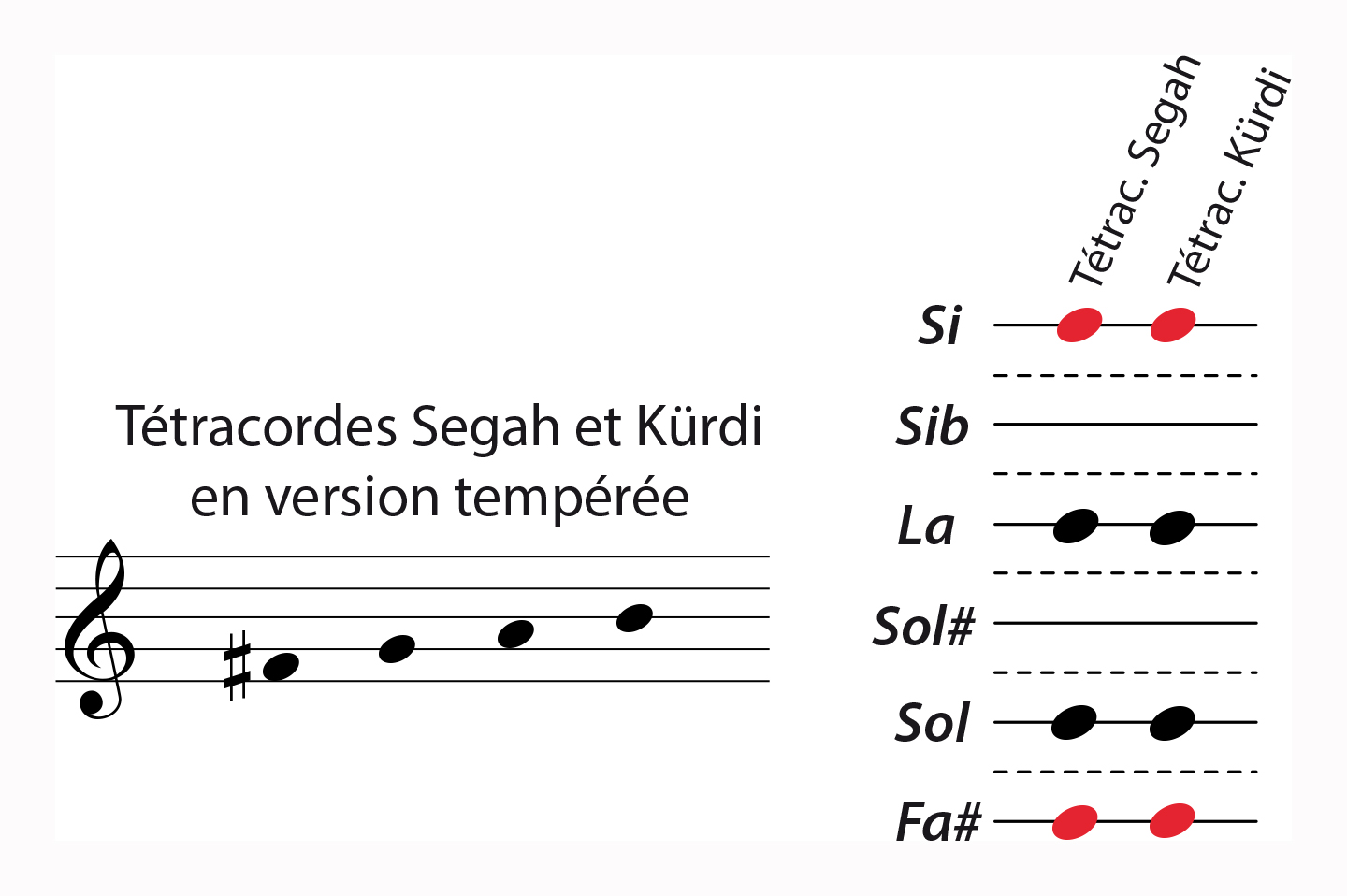

Samir plays a more tempered version of the Segah tetrachord, which allows him to move from the Eviç makam to the Kürdi makam without shifting any degrees and without altering the drone.

The tempered Segah and Kürdi tetrachords

As for the modern tempered version, it harmonizes in major and adds a melody a third lower:

"Zaplakalo e Mariovo," by Petranka Kostadinova, 1999. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9LqTGTm-LxI. Album: Macedonian Folk Songs, licensed to YouTube by The Orchard Music (on behalf of Mister Company) and a music rights management company.

The Eviç mode in the song "Çalın Davulları" and transcription issues

This is why we find two possible key signatures for this piece:

- The key signature usually used for the Eviç makam, so by seeing it we know that we are in the makam system with unequal temperament and that the first degree is a slightly low F#. The C# does not appear in the key signature but is notated here as an accidental.

- Either with the key signature of D major—two sharps in the clefs of F# and C#—and we are apparently in equal temperament.

Unlike Ottoman classical music, Turkish folk music (of which “Çalın Davulları” is a part) is often less rigorous in its transcriptions. Thus, non-equal temperamental accidentals are not necessarily notated, and one might think, upon reading a transcription of “Çalın Davulları,” that one is dealing with a simple major mode. In general, musicians have already internalized the intonations specific to Turkish music, and in this particular situation, even with an inaccurate key signature, they will still respect the unequal temperament of the Eviç makam.

The “Eviç” mode by Samir Kurtov

During the taksim introducing “Çalın Davulları,” Samir does not respect the descending temperament of the Eviç makam. It begins in the lower register, then ascends to the octave before descending again. This melodic form more closely resembles the behavior of the Segah makam. This is because, unlike in Turkey, the theoretical frameworks of Ottoman music are not currently practiced in the Balkans, and consequently, the question of whether or not to adhere to the traditional makam structure is not really relevant. After all, the Eviç and Segah makams are very similar and essentially the same if one is unfamiliar with the rules of Ottoman music.

Taksim, by Samir Kurtov © Drom 2020

The Ambiguity Among the Eviç Family Makams

In the Eviç family makams, the tetrachord beginning on the third degree can be confusing. In the Ottoman theory version of the Eviç makam, the 5th degree is pure (C), so we consider that from the 3rd degree onward, we have the Ushak tetrachord. In the “Çalın Davulları” version of the Eviç makam, the 5th degree is augmented (C#), so the Ushak tetrachord disappears and is replaced by a tetrachord that can be interpreted and tuned in various ways.

The Ambiguity Between Tetrachords, by Laurent Clouet. © Laurent Clouet - Drom 2021

The Temperament of the Drone

Contrary to Ottoman theory, in this video the first degree of the mode (which is also the drone played by the zurnas) is tempered. This allows Samir to modulate in the Kürdi makam for the following piece, “Bir Ayrılık Bir Yoksulluk Bir Ölüm,” which, once again, is not very conventional from the perspective of Ottoman music.

Indeed, if the tonic were the original tonic of the Eviç makam (that is, a degree slightly lower than a tempered degree), it would have to rise by a comma to move from the Eviç makam to the Kürdi makam.

The Segah and Kürdi tetrachords are not tempered.

Here, the Kürdi tetrachord is notated on the staff starting from A, as is the custom in Ottoman music, but the tetrachord scales remain parallel in the diagram to illustrate the differences between the two tetrachords.

Samir plays a more tempered version of the Segah tetrachord, allowing him to transition from the Eviç makam to the Kürdi makam without changing the degrees or altering the drone.

The tempered Segah and Kürdi tetrachords

Temperament in the Balkans and Ottoman Theory

In the music of the southern Balkans, the question of temperament, intervals, and intonation is complex, given the numerous cultures present in the same territory.

The temperament used varies according to style, period, region, and musician. It can also differ from one piece to another or even within the same piece.

However, we can identify some major influences involving different temperaments:

- Ottoman and Byzantine music

- Western music with equal temperament

- The temperament inherent in the construction of the zurna itself

- The temperament inherent in other instruments such as the gaïda or the clarinet

- Other Balkan and Turkish music

- Arab, Egyptian, and Near Eastern folk music.

- Indian music (Bollywood, pop music)

In the music of the Bulgarian Roma, there are no pre-established rules or authority implying any hierarchy regarding the choice of temperament. Musicians demonstrate great creativity and constantly renew the modes used, notably by modifying their pitch in order to generate musical tension and intense emotions.

Ottoman music theory in Balkan music

Since temperament is variable, so too is the understanding of modes. Again, theoretical conceptions change according to the performers, the regions, and the eras.

Having been under Byzantine and then Ottoman rule, the Balkan countries were musically uninfluenced by these cultures using unequal temperament. Following their independence in the 19th century, they turned to the major European powers and thus adopted the theory of Western classical music with equal temperament to describe and transcribe their music.

Lately, there has been a kind of “return to the roots,” and some musicians are increasingly referring to Ottoman music theory to theorize the music of the southern Balkans. This system seems better suited to their music for three reasons:

- it allows for the notation of commas

- it highlights the superimposition of tetrachords and the resulting modulations system;

- it takes into account regional modes by moving beyond the harmonic system, thus allowing for key signatures other than those following the order of sharps and flats.

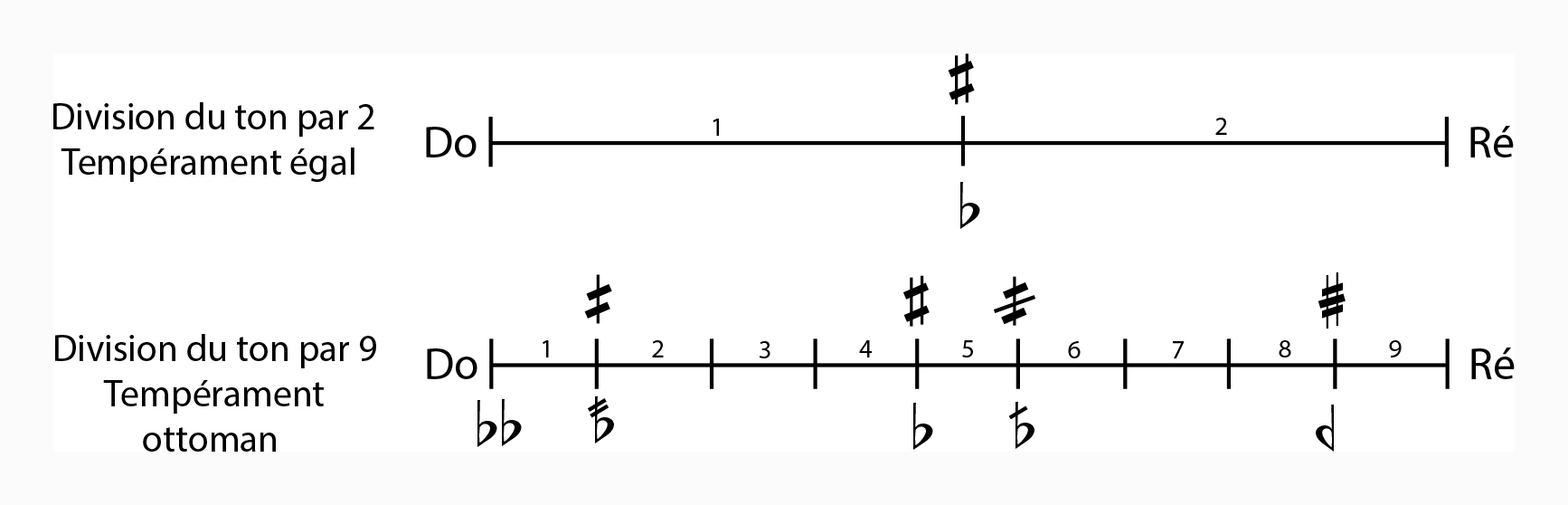

The Notation of Commas in Ottoman Music

From the late 19th century onward, Ottoman musicians felt the need to transcribe their music onto sheet music. The notation system of Western classical music did not allow for the writing of music in unequal temperament, since it divides the whole tone into only two semitones. To account for the subtleties of temperament, what are commonly called "quarter tones," Ottoman theorists divided the whole tone into nine equal parts, or nine commas.

Comparative diagram of the division of the whole tone in Western classical music and Ottoman music:

The sharp and flat accidentals used in Ottoman music do not correspond to the same pitches as these accidentals in Western music. For example, the Ottoman sharp is a half-comma lower than its Western counterpart. They are therefore very close. These subtle differences in intervals make it not always easy to identify untempered degrees in Ottoman music.

Furthermore, this diagram indicates that Ottoman music uses only the 1st, 4th, 5th, and 8th commas. In analyzing the performed suite, we see that this system of division into 9 pitches does not correspond to the actual performance. The pitches of the commas can therefore occupy positions different from those proposed by modern Ottoman theory. The latter proposes a theoretical temperament intended to allow musicians to understand the melodic framework within which they find themselves.

The Vocabulary of Ottoman Music

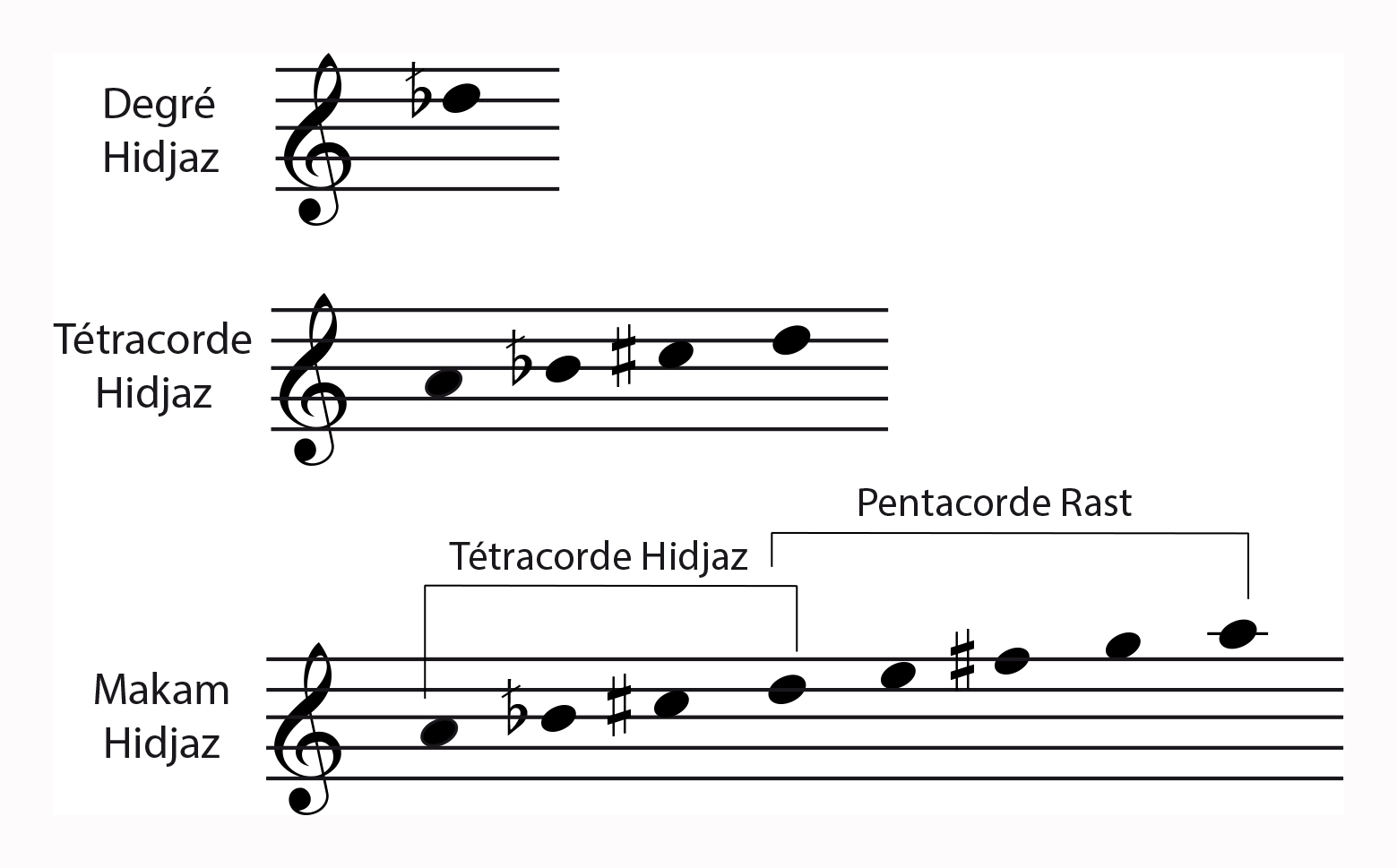

In Ottoman theory, names—of Arabic and Persian origin—such as Hijaz, Segah, Eviç, Irak, Kürdi, etc., can signify three distinct things

- a makam

- a tetrachord

- a degree

To ensure clarity, I will specify what I am referring to each time.

For example, the term “Hidjaz” can refer to a makam, a tetrachord, or a scale degree:

Makams and Tetrachords

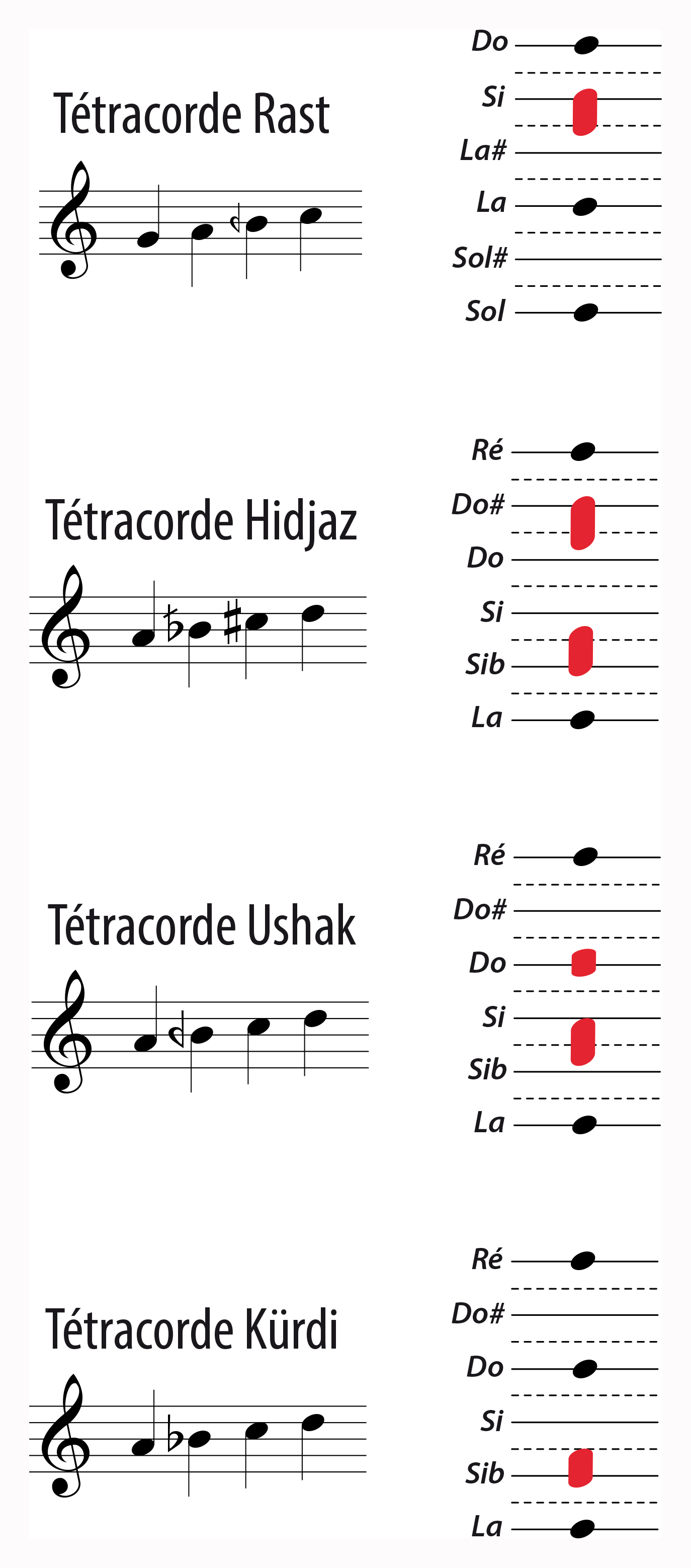

The terms tetrachord and pentachord are frequently used in Eastern music, referring to a sequence of four or five notes.

To form a makam, for example, two tetrachords are superimposed, or a tetrachord and a pentachord, resulting in a scale that most often has seven notes.

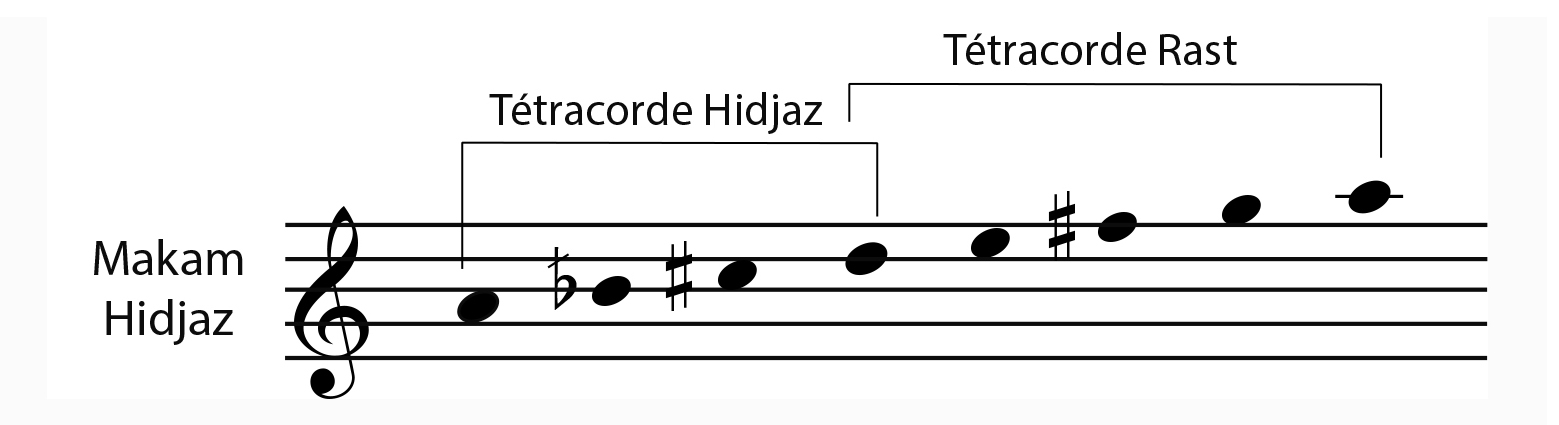

This is the case with the makam Hidjaz, that is formed from the tetrachord of the same name, "Hidjaz," and the pentachord, "Rast."

The melodic behavior of a makam is essential for its description and recognition. For example, some makams have a predominantly ascending melodic form, while others have a descending one.

The Implications of the Tetrachord Superposition Approach to Modes in Musical Practice

This analysis of modes through tetrachord superposition has implications for melodic forms. Indeed, the forms can differ for the same makam depending on which tetrachords the musician wishes to emphasize.

For example, for the Hidjaz makam, there are two possible constructions:

- the Hidjaz tetrachord on the 1st degree, then the Rast tetrachord on the 4th degree;

- the Hidjaz tetrachord on the 1st degree, then the Ushak tetrachord on the 5th degree;

In the first version, the musician will focus on the fourth and play the melodic forms of the Rast makam, while in the second, they will focus on the fifth and play the melodic forms of the Ushak makam.

Understanding Hicaz, by Laurent Clouet. © Laurent Clouet / Drom

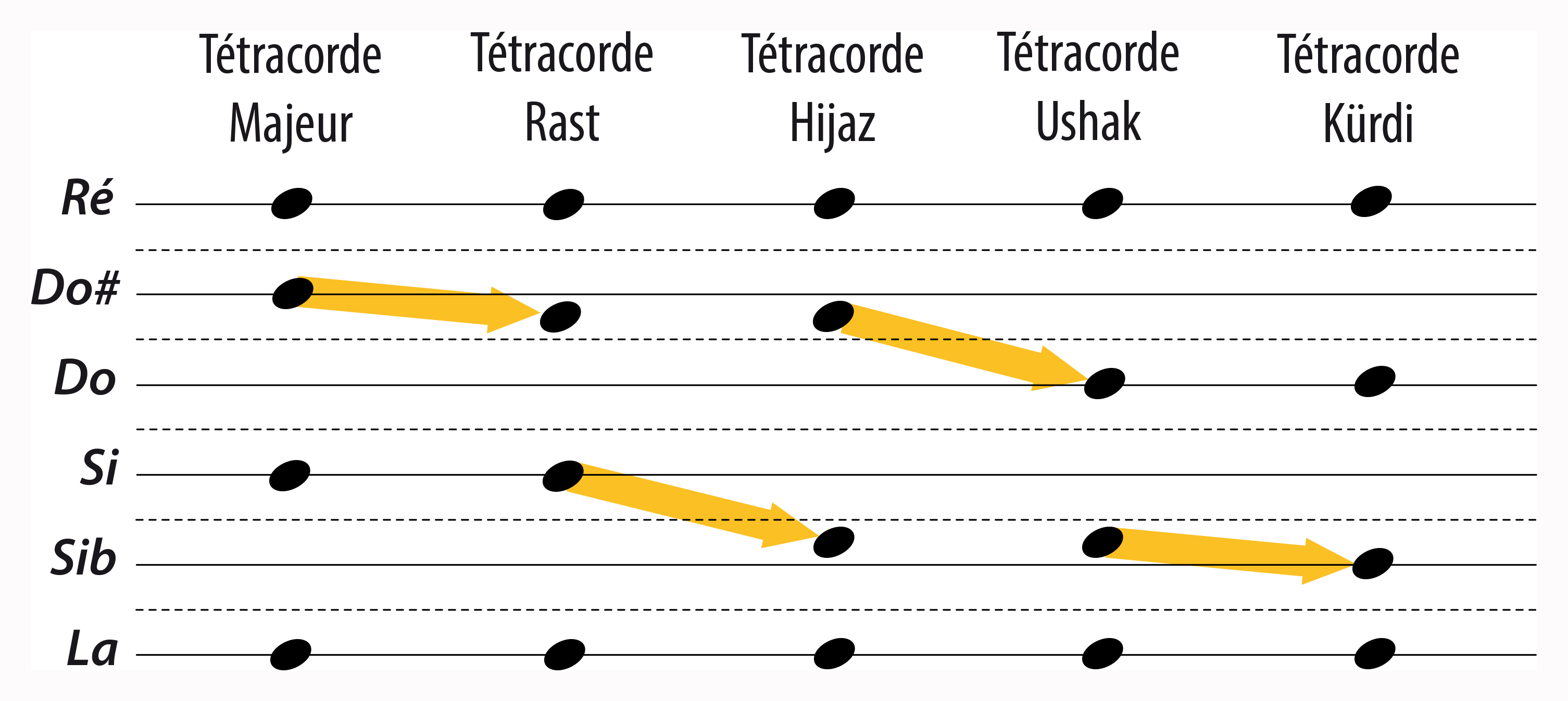

The Temperament of Tetrachords

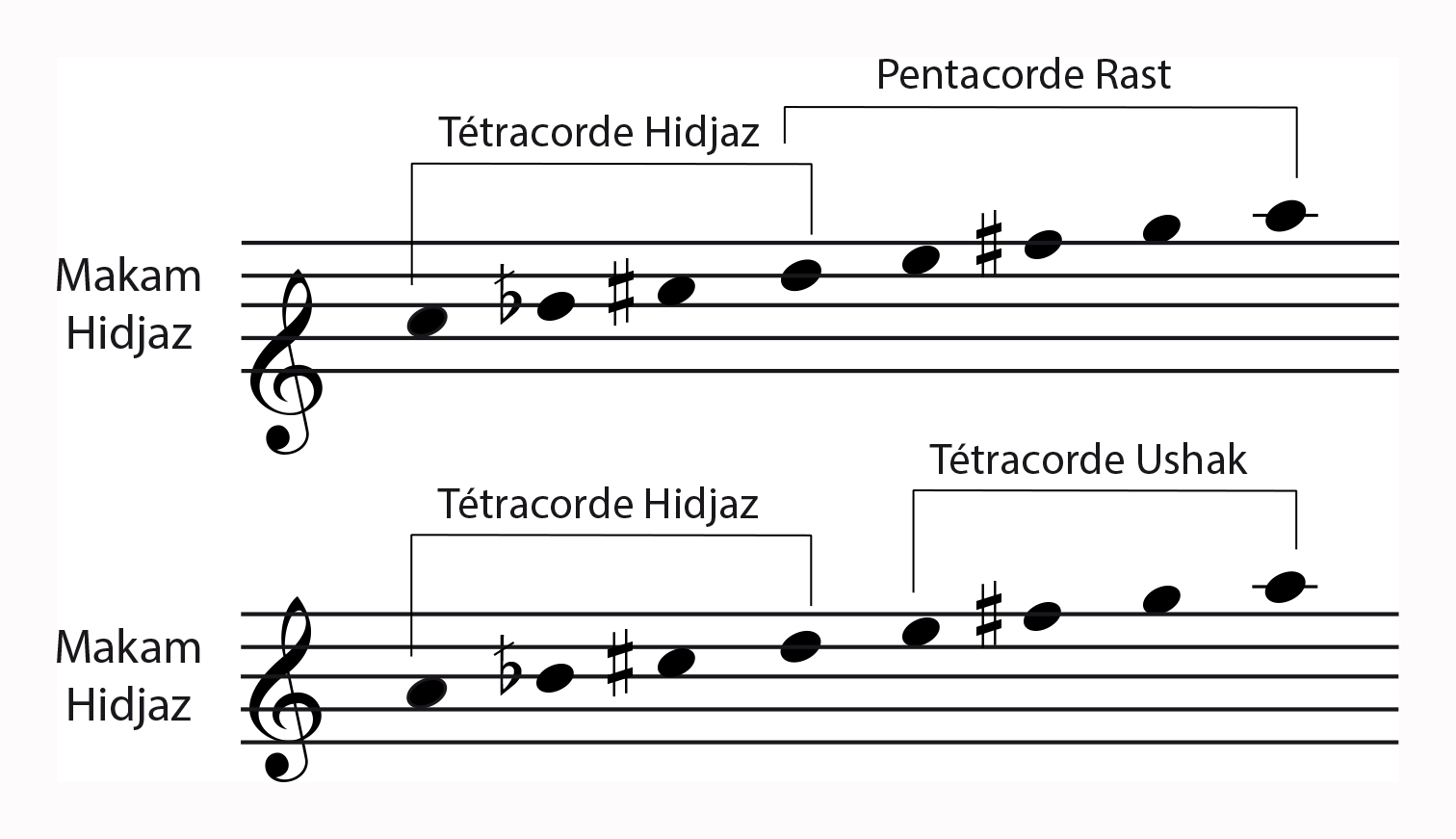

By examining the intervals of tetrachords in the Balkans (and more generally in music with unequal temperament), we observe that there are several possible pitches for certain degrees.

To make these temperamental subtleties clear, the tetrachords will be presented on a "vertical scale," allowing visualization of the relationships between the degrees of a single tetrachord and comparison of different tetrachords:

The Rast, Hijaz, Ushak, and Kürdi tetrachords offer several possible intervals.

In the diagrams below, these notes with variable pitch are shown in red.

Left: Notation for Ottoman music

Right: Solid lines: whole tones; dotted lines: quarter tones.

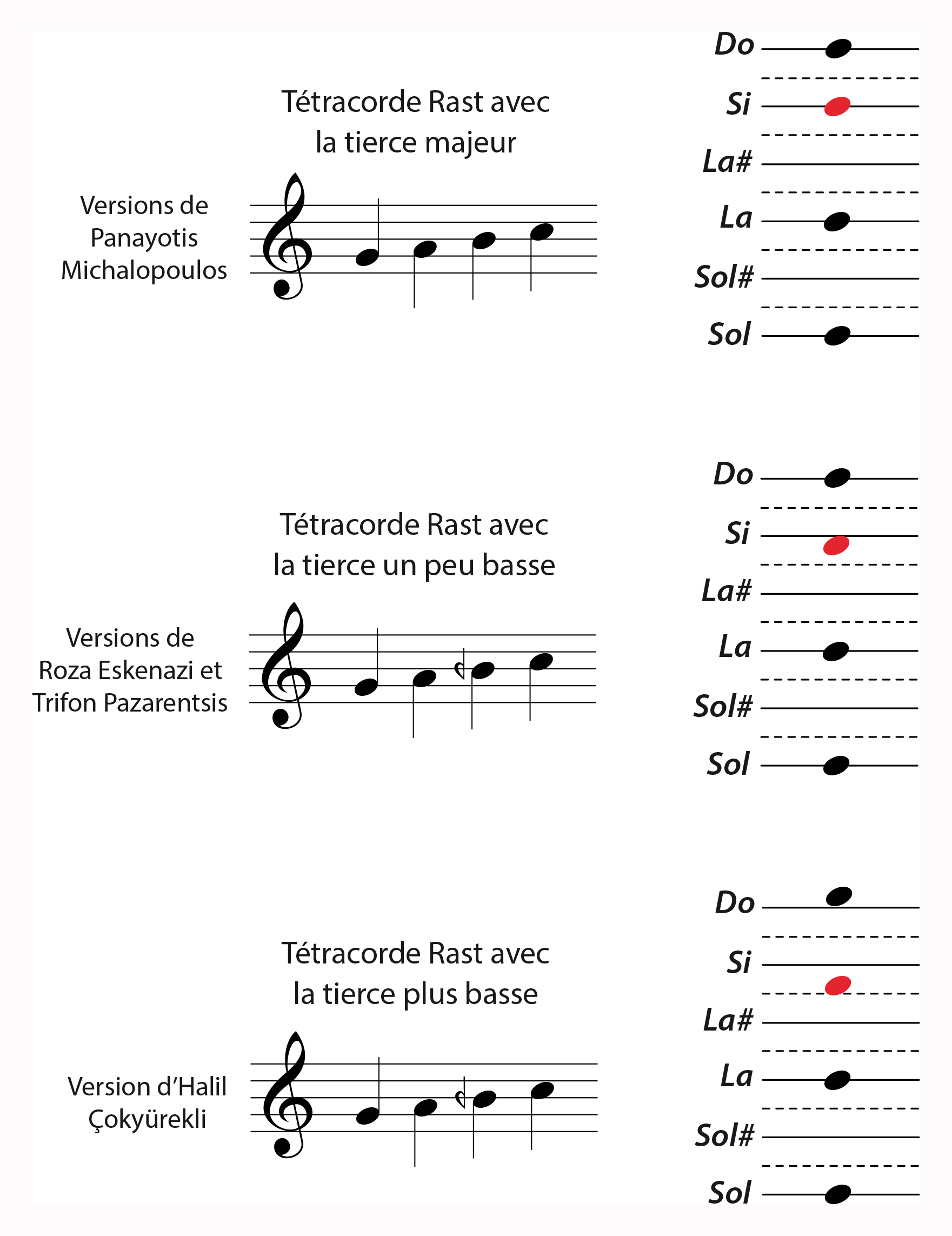

Examples of temperaments with the Rast tetrachord

For the Rast tetrachord, which is the basis of the Rast makam, the third (B) can be played at different intervals: it can be played perfectly, slightly lower, or even lower, a quarter tone below.

For example, with the emergence of the bouzouki in Greece during the 20th century, the makam rast was performed in equal temperament. This is because the instrument has fixed metal frets, and is therefore tuned to equal temperament. Despite this, the makam rast is recognizable; it is only through its melodic character that it is distinguished from the major mode.

For example, in the Greek song “Kanarini mou gliko” (Καναρίνι μου γλυκό), the temperament varies depending on the orchestration:

In Roza Eskenazi's version from the 1930s, the oud, violin, kanun, and voice play rast in unequal temperament:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dz2krRupnI8. Vocals: Roza Eskenazi, violin: Dimitris Zemsis, oud: Evaggelos Toboulis. Balkan Amérikis disc BAL-4047, licensed to YouTube by The Orchard Music, Digital Minds Ltd-srav, and two other companies.

In Panayiotis Michalopoulos's 1960s version, the bouzouki, violin, and santur (but not the voice) play Rast in equal temperament.

Another example, this time with zurnas : two examples presenting two different temperaments of Rast:

Nizamikos by Trifon Pazarentsis. Here, the third is slightly lower than that found in equal temperament:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ezYZWR6d57Y. Vocals: Panaghiotis Mikhalopoylos. Record: Den Xanakano Filaki Me Ton Kapetanaki ℗ Atheneum Greece 1997.0 Released on: 1997-03-27. Licensed to YouTube by Digital Minds Ltd-srav.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LKcdK2PGbHU&ab_channel=Greek_Culture. Zurna: Trifon Pazarentsis, saxophone: Stavros Pazarentsis.

Taksim (unmeasured improvisation) in Rast by Halil Çokyürekli. Here, the third is lower than the previous recording:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VkkvlqPAUU0. Zurna: Halil Çokyürekli. Halil Çokyürekli's YouTube channel

Below are the diagrams of the different versions of the Rast tetrachords in these recordings:

The same notation can be used for both unequal temperament versions with the flat reversed, even though the temperament is not the same. The notation never perfectly indicates the exact pitches since the musicians' interpretive choices take precedence over theory.

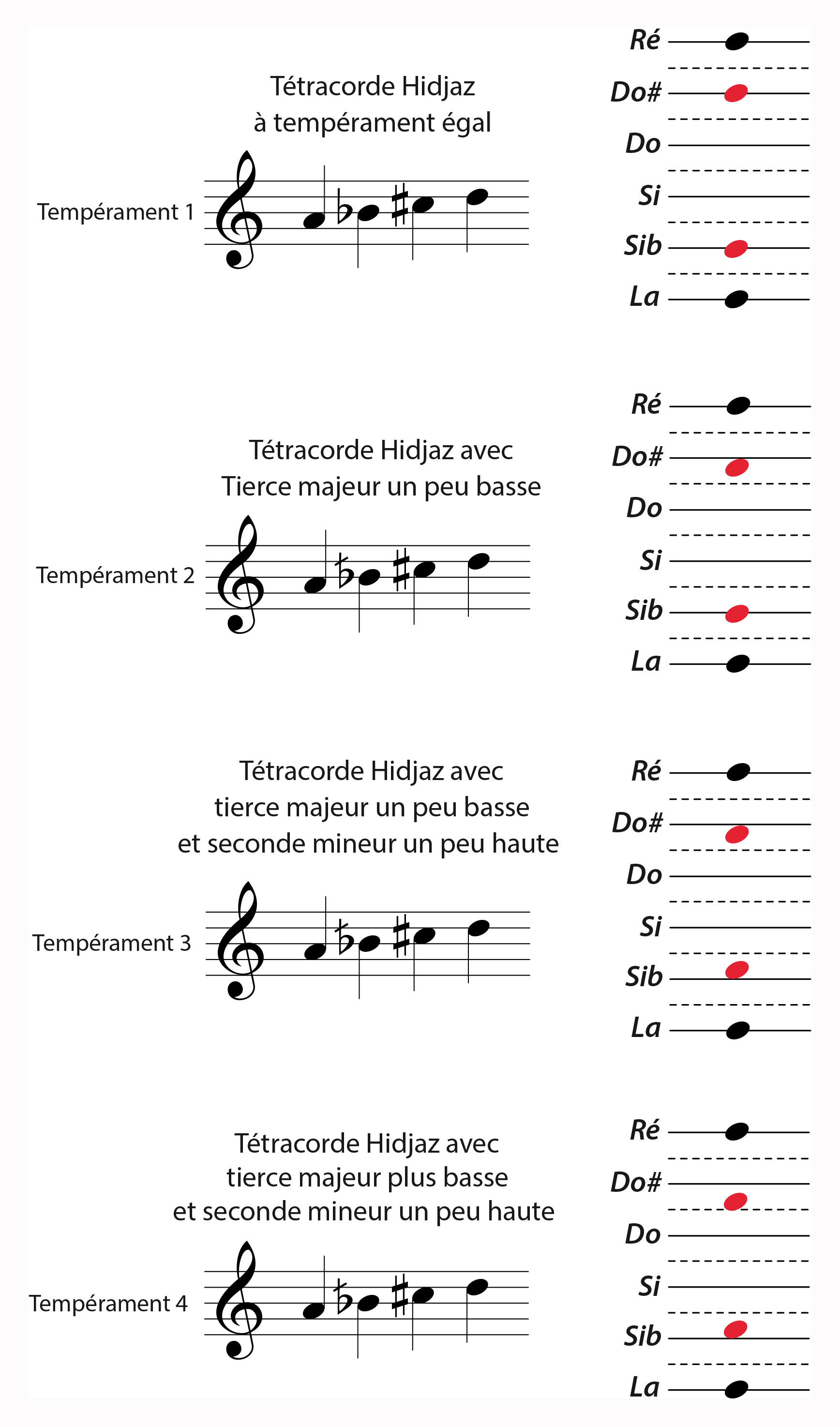

Examples of temperaments with the Hijaz tetrachord

For the Hijaz tetrachord, the second and the third can occupy several positions, which I play here, and whose diagrams for the different versions played are given below:

Different Hijaz tetrachords, by Laurent Clouet. © Laurent Clouet-Drom

Tout comme pour l'exemple précédent avec le tétracorde rast, on utilise la même notation pour des tempéraments différents. En effet, les tempéraments 2, 3 et 4 sont notés de manière identique pour des hauteurs réelles différentes.

Just as with the previous example with the Rast tetrachord, the same notation is used for different temperaments. Indeed, temperaments 2, 3, and 4 are notated identically for different actual pitches.

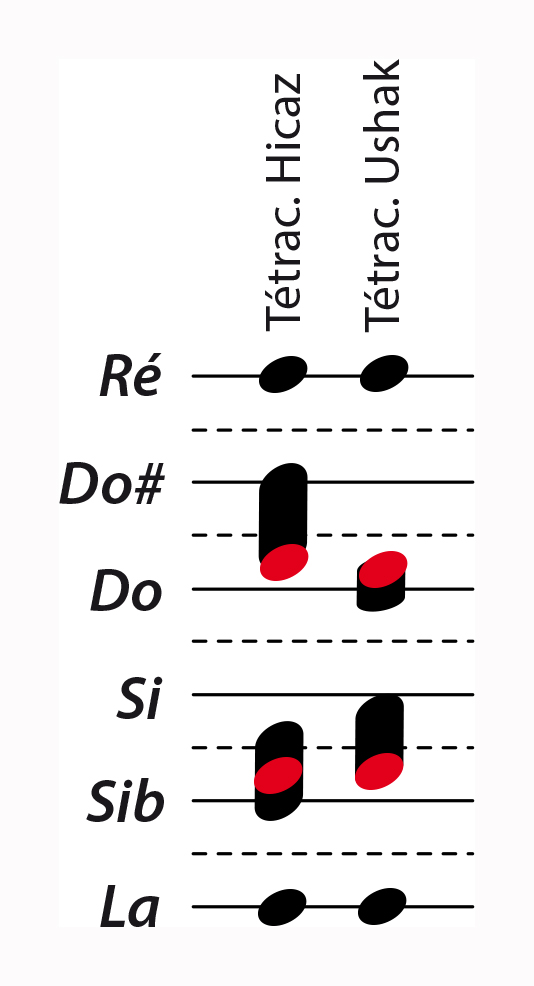

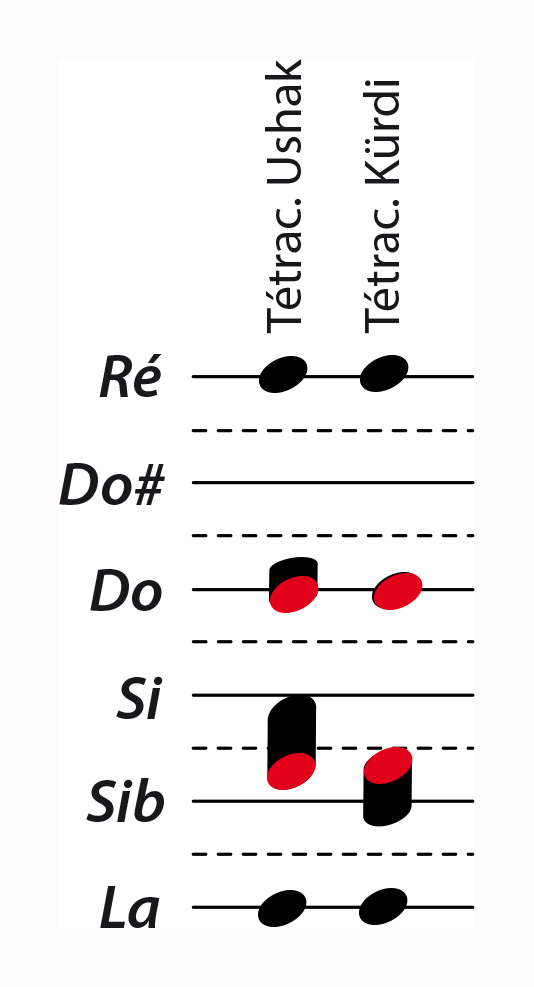

Ambiguity between tetrachords

The elasticity of the degrees means that some tetrachords can be confused with one another, which is often a deliberate choice on the part of musicians.

For example, lowering the third and raising the second of the hijaz tetrachord brings it closer to the ushak tetrachord:

Lowering the second of the ushak tetrachord and raising that of the kürdi tetrachord brings the two together:

Ambiguity between tetrachords, by Laurent Clouet. © Laurent Clouet-Drom

Ornamentation in Balkan Music

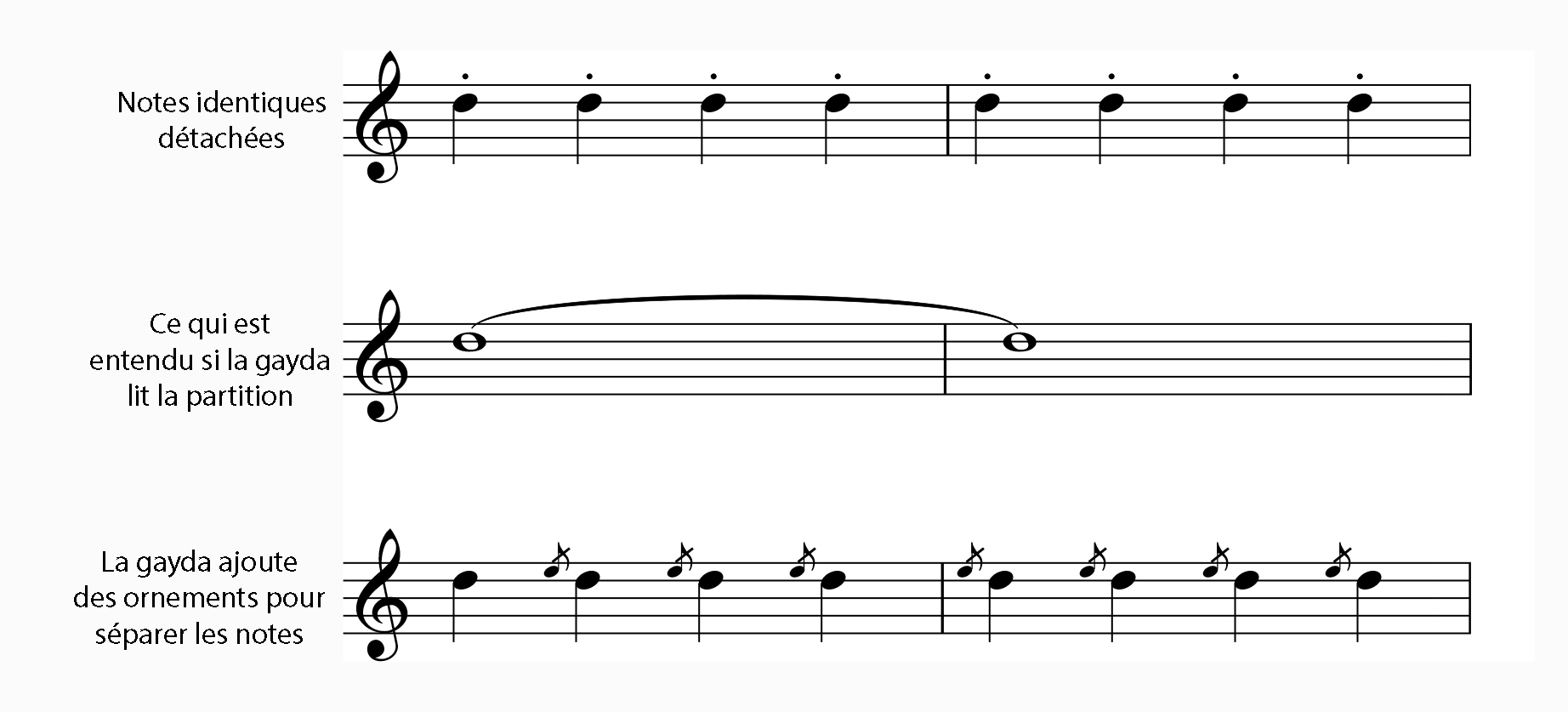

Balkan music is highly ornamented. This is probably due to the fact that the gaïda, or other forms of bagpipes, is at the origin of this music.

This type of instrument cannot phrase melodies using the tongue as one would an instrument where the mouthpiece, the part that produces the sound, is in contact with the mouth. This is the case, for example, with the zurna or the clarinet.

Thus, the only way to separate two identical notes is to insert a short, even almost inaudible, note between them: this is ornamentation.

The Gaida System

All other instruments played in the Balkans very often imitate the gaida playing style. Over time, they have added their own ornamentation and phrasing, but the basic principle remains the same.

There are many types of ornaments and phrasing, which are categorized into different styles. These styles correspond to a country, a region, an ethnic group, a period, or an artist. Thanks to ornamental style, musicians or listeners can sometimes immediately recognize the geographical origin of a piece. Ornamental playing is therefore very important for differentiating styles from one another. Thus, the same melody can be played in a different style.

Ornamentation Notation:

For the sake of readability, not all ornaments are notated, and often there are simply none in the scores. However, Balkan musicians reading a score know which ornaments are played and when, since they have already internalized the style of their own music. There is therefore a system, rules, and principles to follow to know how to ornament according to different styles.

Ornamentation in “Gaydarsko Horo”:

In the last theme, Samir imitates the Bulgarian gaida style, which is recognizable by the following elements:

- Phrases played in short, repeated cells with slight variations

- The use of pedal notes

- The ornaments and phrasing characteristic of the gaida.

Here is the video and transcription of the different parts of “Gaydarsko Horo.” The transcription is written in mixolydian G for readability, as the original is in C#. The pedal notes are in red.

*vidéo séquencée*

Here are the first phrases of each part with the exact ornamentation and phrasing. As you can see, the large number of ornaments makes it difficult to read.

With this example, we can identify 5 types of ornamentation and propose a small "grammar of Bulgarian phrases":

Historical and social contexts of musical practice in Bulgaria

A Brief Historical Context

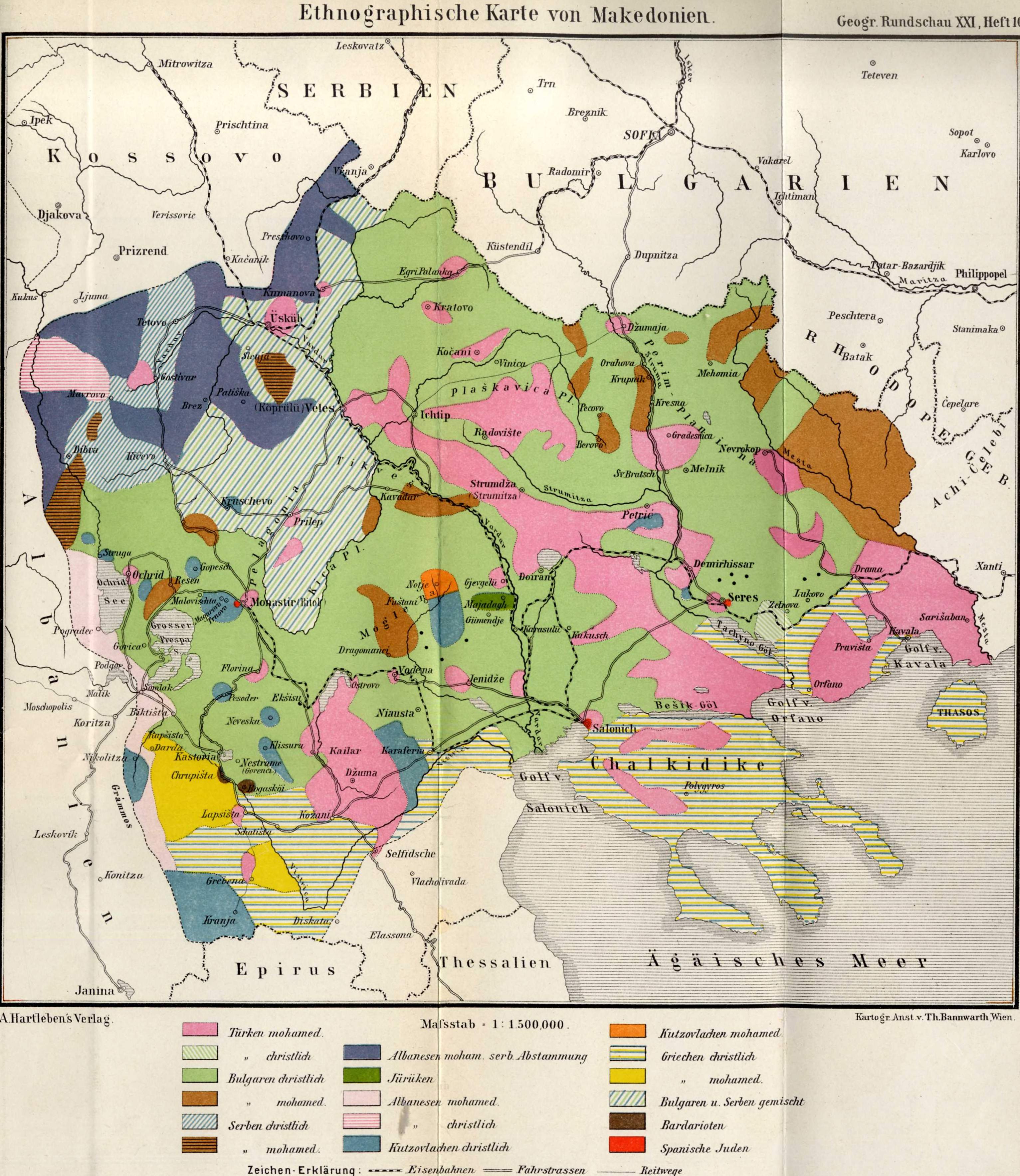

The Balkans, Macedonia and Bulgarian Macedonia, Roma and Gypsies

Samir Kurtov lives in the village of Kavrakirovo. It is in Bulgaria, very close to Greece and North Macedonia. This border region is called Pirin or Pirin Macedonia, in reference to the mountain range of the same name, or even Bulgarian Macedonia. But if we are in Bulgaria, why do we talk about Macedonia? Aren't they two different territories?

To fully understand this part of southeastern Europe and the fragmented political landscape of the countries that comprise it today, it is essential to first understand the history of the Ottoman Empire and especially the period of its disintegration, which took place from the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century and is generally referred to by historians as the "Eastern Question."

From the 14th century onward, the armies of the Ottoman Empire, a newly formed Turkish province then located west of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), crossed the Bosphorus and gradually seized southeastern Europe, precipitating the fall of both the Serbian Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire (of Greek Orthodox culture, now known as the Byzantine Empire), which culminated in the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Unlike Anatolia, and despite the settlement of Turkic-speaking Muslim populations and the conversion to Islam of some of the region's native inhabitants, it remained predominantly Orthodox Christian. Thus, to refer to the European part of the Ottoman Empire, its inhabitants used the term "Rumelia," meaning "Land of the Romans," in reference to the vanished Eastern Roman Empire.

The administrative and legal organization of the Ottoman Empire by religious communities was the defining characteristic of its political system. Ottoman citizens recognized and identified themselves primarily by their religion: Muslims, Jews, or Christians. It was from the 19th century onward that nationalist movements developed, influenced by Enlightenment ideals, and this is how we see the "rebirth" of peoples who identified by a common language, such as the Greeks, Bulgarians, and Romanians. Taking advantage of the weakening of the Ottoman Empire and the military and diplomatic support of the major European powers (Russia, France, and Great Britain), small nation-states gained their independence: Greece (1821), Romania (1859), Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria (1878), and Albania (1912).

However, until 1912, a significant portion of Rumelia still belonged to the Ottoman Empire. This is the case of the region we now call Macedonia. In the 19th century, this term was used only by geographers and other European scholars, in reference to the ancient Kingdom of Macedonia of Alexander the Great (356–323 BC), but it did not yet have a political meaning. Within the Ottoman Empire, the region was referred to as the vilayets (provinces) of Thessaloniki, Bitola, and Skopje, the major cities of the region.

The Balkans from 1878 to the First Balkan War: Balkans 1878-1912

Map by Spiridon Ion Cepleanu, based on William Miller, *The Ottoman Empire, 1801-1913*, Cambridge University Press, 1913. © Spiridon Ion Cepleanu, Creative Commons

The newly independent neighboring nations (Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria) supported an irredentist policy and claimed all rights to this territory, which was embroiled in civil war. They sought to exacerbate the situation in order to seize it. This led a portion of the local population to define themselves by a new identity that was neither religious nor linguistic, but geographical: rather than being Bulgarian, Greek, or Serbian, one could now be Macedonian, which, among other things, allowed them to avoid having to choose a side.

Ultimately, despite their antagonisms, Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia allied themselves during the First Balkan War (1912-13) to push back the Ottoman Empire to the borders of Europe. It was from this event that the use of the word "Balkans," which originally referred to the mountain range in central Bulgaria (Stara Planina in Bulgarian) and by extension a mountain range, became truly popular in European newspapers and supplanted the terms "Rumelia" and "European Turkey." Numerous conflicts followed, including the Second Balkan War and two World Wars, culminating in treaties that redefined the partition of Ottoman Macedonia. Today, this territory is divided primarily between three countries:

- Greece (Aegean Macedonia or Greek Macedonia, comprising 52% of Macedonian territory)

- North Macedonia (Vardar Macedonia), which emerged from the breakup of the former Yugoslavia (35.8% of the territory)

- Bulgaria (Pirin Macedonia or Bulgarian Macedonia, comprising 10.1% of the territory).

Map of Macedonia. © Laurent Clo

North Macedonia has been known for its multi-ethnic character since the 19th century. At that time, numerous languages were spoken there: Greek, Albanian, Aromanian or Valach (related to Romanian), Slavic Macedonian (related to Bulgarian), Serbo-Croatian, Turkish, Romani or Romani (the language of the Roma), and Ladino or Judaismo (the language of the Sephardic Jews).

Furthermore, the three major monotheistic religions (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism) were present in various forms. European ethnologists, in seeking to define a precise identity for each people of Macedonia or the Ottoman Empire, associated a religion with a language: Muslim Bulgarians, Christian Albanians, Greek-speaking Jews, and so on.

MUnfortunately, in most Ottoman territories, the conflicts of independence led to numerous massacres and population displacements, resulting in ethnic cleansing fueled by an ideology advocating the construction of nations homogeneous in both religion and language. Even though a certain degree of religious and linguistic diversity can still be observed today, particularly in North Macedonia and Bulgarian Macedonia, the Macedonian region as a whole has not escaped this violent history and is no longer as cosmopolitan as it once was.

Ethnographic map of Macedonia (1899), source Wikipedia, Deutsche Rundschau für Geographie und Statistik Vol. XXI, Issue 10. Author: Friedrich Meinhard.

Samir Kurtov is an emblematic representative of this Ottoman heritage. His native language is Romani; he also speaks the Macedonian dialect of his region and Bulgarian, the official language of his country. He also knows some Turkish because his ancestors were Turkish-speaking and Muslim, and converted to Christianity, probably to avoid being expelled to Turkey during the Balkan Wars. In fact, some of his ancestors came from Greek Macedonia, from where they were expelled.

Although Macedonia does not correspond to a single country or a distinct cultural zone, one can nevertheless recognize, through its music, certain shared melodic forms and a common style characteristic of this area, which allows us to hypothesize that a relatively ancient cultural unity exists.

Roma and Gypsies

Defining the identity of the Roma people presents a number of difficulties. If one considers the Roma as a single, homogeneous people, they do not possess a state or representative political structure that would allow them to constitute themselves as a nation. Furthermore, even though some consider them the largest minority in Europe, they remain a significant minority in most of the countries concerned (less than 1% of the population), except in the Balkans where they officially represent 2 to 5% of the population and 6 to 12% according to a high estimate. This statistical difference, ranging from one to two percent, demonstrates how problematic it is to define and delimit the identity of this minority.

First and foremost, the term “Roma” can be confusing because it is often associated with the Romanian people and their country, Romania. However, although Roma are numerous in this territory, we are dealing with two distinct etymologies:

- “Romanian” originally refers to the Roman Empire, which is also the case for “Roum,” a word that designates an inhabitant of Rumelia.

- “Roma” comes from Romani, the language of the Roma, and designates a married man (an adult) within the community. For a woman, the term “Romni” is used.

In the Balkans, the term “Roma” was initially used primarily within the Roma community. “Tsiganin” in Bulgarian, “çingene” in Turkish, “cigan” in Albanian, “athigganos” or “giftos” in Greek (the first two giving “tsigane” in French and the last “gypsy” in English) are the words still used today by people outside the Roma community to refer to them.

In Europe, however, with their political recognition as a minority over the last 50 years, the term “Rom” has become the official designation, and the other terms are gradually perceived as pejorative. Thus, a Roma person might sometimes call another Roma person “tsigane” if they want to belittle them.

The question of who is Roma and who is not is one of the most debated issues, both among academics and among the Roma themselves. Currently, although several theories exist, everyone agrees that this people left northern India starting in the 10th century, gradually moving towards the Mediterranean basin. As for the Balkans, the first evidence of their presence dates back to the 14th century. It is thanks to their language, Romani, which belongs to the Sanskrit family, that their Indian origins have been discovered. Although not all Roma speak Romani, the most objective way to identify a Roma is to know if they speak Romani, or if the language spoken contains vocabulary borrowed from Romani. This is the case, for example, with the Turkish Roma of the southern Balkans, who speak Turkish with a few Romani words.

In this same region, the patchwork of languages and religions inherited from the Ottoman era makes it difficult to categorize all the peoples living there within a single, defined identity framework. The Roma complicate matters further because each family possesses, in addition to its own Romani culture, the culture of the country where it lives and sometimes even that of the minority to which it is related. In Bulgaria, the Roma all speak Bulgarian, which is the national language; some speak Romani, others Turkish, some only Bulgarian, and others all three languages. Still others speak Valach (related to Romanian) because they live alongside speakers of that language. They can be Christian or Muslim, although Turkish speakers are generally Muslim, but some Roma practice both religions. It is said that they are baptized by the priest and buried by the Imam.

The main reason why Roma population figures vary in the Balkan countries is that they do not necessarily identify themselves as such in censuses. Thus, in Bulgaria, Turkish Roma generally define themselves as Turkish rather than Roma. Other Roma may define themselves as Bulgarian without specifying that they have Roma origins. Therefore, until recently, Roma were not included in censuses or ethnic mapping because they were always grouped with other ethnic groups.

Reference: MAZOWER Mark, The Balkans. From the End of Byzantium to the Present Day, ed. Weindenfeld & Nicolson, 2000.

Playing Contexts in the Balkans

When discussing popular, traditional, or folk music in the Balkans, each nation refers to pastoral music as the purest source and most authentic playing context: a shepherd tending his flock and playing ancestral melodies on an instrument, usually a flute, that he has crafted himself. This historical representation is reenacted at costumed folk gatherings.

Yet, even though the rural world has changed dramatically during the 20th century, pastoralism is becoming increasingly rare in the Balkans, and traditional village society has almost disappeared, family and community events such as weddings, baptisms, circumcisions, funerals, carnivals, and village festivals have not ceased. These celebrations provide numerous opportunities to hire professional musicians, who are frequently from the Roma community. Indeed, some Roma families have dedicated themselves solely to music for generations.

Playing at these popular festivals requires specific skills. Weddings, for example, last all day, and the music practically never stops. Musicians must therefore be resilient and able to seamlessly transition between themes and improvisations over an extended period. Generally, the same group is hired for the entire wedding festivities. However, nowadays, it's common to hire a davul-zurna (a traditional Roma musician) for the opening act in the street, then an orchestra for the restaurant, and finally for the party in the village or neighborhood square.

Another crucial point is that music is performed on demand, often in exchange for baksheesh, meaning payment in the form of money. The audience plays a crucial role, acting as both listeners and participants, since they choose the dances and songs, and as customers, often paying the musicians directly. To make a living from their art, musicians must be able to respond to a wide range of requests and therefore possess a vast and varied repertoire, which differs depending on the village, community, and generation. Thus, divisions by era, classifications by region, and distinctions between traditional, pop, national, and foreign music become irrelevant when the repertoire is dictated by the audience.

For these reasons, individual achievement as an artist is rarely discussed in these circles; musicians emphasize their virtuosity, their knowledge of the repertoire, or their ability to develop their style to the highest level.

Musical Learning and Transmission in Bulgaria

The teaching of folk music, and in our case, music in Bulgaria, is primarily done through oral transmission, imitation, and immersion.

That being said, in Roma musical families, learning music is often a far more conflictual process than one might imagine.

Indeed, sometimes a child doesn't choose their instrument. It may be assigned by their father according to his needs—if the father is a clarinetist, he will need a kanun (table zither), an accordion, or a keyboard instrument to accompany him. He may even go so far as to forbid his son from playing an instrument (the clarinet, for example), which often has the opposite effect, namely a tenfold desire for that instrument. It is said of the famous Bulgarian Roma clarinetist Ivo Papazov that his father had intended him to play the accordion. There was indeed a clarinet in the house, his father's, but he wasn't allowed to touch it. Nevertheless, he began to play it when his father was away. One day, his father returned from work and heard someone playing the clarinet beautifully at home. Upon entering, he was surprised to see his son with the instrument in his hands, and he told him to give up the accordion.

Furthermore, within the family setting, the young musician doesn't necessarily receive formal lessons; he has to gather information to develop his skills independently. When lessons do exist, the frequent father-son conflicts regarding learning often lead to the sons being sent to another musician to study.

The concept of "disciple" doesn't really exist, and respect for older generations isn't a given. Most aspiring musicians want to break free from their parents by playing a more modern or recent repertoire, abandoning the outdated music of their ancestors.

Access to repertoire, whether old or new, is naturally gained through contact with family members and also through videos on the web, but it is primarily at the numerous weddings they attend that young musicians train their ears.

Finally, to be considered a professional wedding musician in Bulgaria, one must first and foremost be able to respond to clients' requests, and it is by understanding this that one learns music, style, and repertoire. Thus, a young musician must quickly acquire the necessary technique to be able to accompany family or colleagues to weddings and progress on the job.

References used

Works :

Bakalov Todor : Maîtres de la musique populaire bulgare - Tome 2 : Les orchestres de mariage - Майстори на народната музика. Том 2: Сватбарските оркестри. Edition : Voennoïzdatelski Kompleks - Direction Georgi Pobedonocets - Sofia 1993.

Yılmaz Zeki : Türk Müzikisi dersleri - Leçons de musique turque. Edition : Çağlar Yayınları - Istanbul 2001.

Djudjev Stoyan : Musique populaire bulgare - Tome 1 - Българска народна музика - TOM 1. Editions : Наука и Изкуство - Science et art.

Articles :

Ipek Metin : "Selânik Türkülerinde Aşk ve Hasret - Love and Longing in Thessaloniki Folk Songs" - "Amour et désir dans les chansons traditionnelles de Thessalonique" - "Balkanlarda Türk Dili ve Edebiyatı Araştırmaları Dergisi", Journal Of Turkish Language and Literature Studies in Balkans / Journal de langue et d’études littéraires turques dans les Balkans, été 2020 - Volume 2 - pp: 97 - 118.

https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/991635

"Türküdeki ses Atatürk'ün değil kameramanın" - "Ce n’est pas la voix d’Atatürk dans cette chanson mais celle du caméraman", Journal « Posta » du 18 novembre 2010,

https://web.archive.org/web/20201004185606if_/https://www.posta.com.tr/turkudeki-ses-ataturkun-degil-kameramanin-50480

Bozkurt Barış, "Features for Analysis of Makam Music - Fonctionnalités d'analyse des Makams", Université de Bahçeşehir, Istanbul, Turquie - 2012 https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiB7fX2wsbvAhWmAWMBHSawBCAQFjAAegQIARAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Fmtg.upf.es%2Fsystem%2Ffiles%2Fpublications%2F2012_3_CMW_Bozkurt.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2OroAbqoNn0RDTC0_tnFVT

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iB4R0JXiioM

Website :

Modulations in Balkan Music

Balkan music is originally built on "modal" melodies based on one or more drones. Harmony, if present, is secondary and therefore does not dictate the structure of the piece. However, this music is not monotonous, and its performers demonstrate considerable inventiveness in creating dynamic musical events.

The most common solution for generating these events is to change the mode; this is called modulation.

If we focus on Bulgarian music, we find three types of modulation:

- changing the mode on the same drone

- changing the drone while keeping the same mode

- changing both the drone and the mode.

The Three Types of Modulation in Bulgarian Music, by Laurent Clouet. © Laurent Clouet / Drom

Using Similarities Between Modes for Modulation

One can move from one mode to another by playing on their proximity, on their shared degrees. By shifting just one or two degrees, one already achieves modulation.

In makam systems, unequal temperament allows for very subtle modulations. By slightly shifting the degrees, one changes modes.

This diagram shows the transition from one tetrachord to another by shifting one or two degrees:

One can also easily modulate when two modes share many degrees.

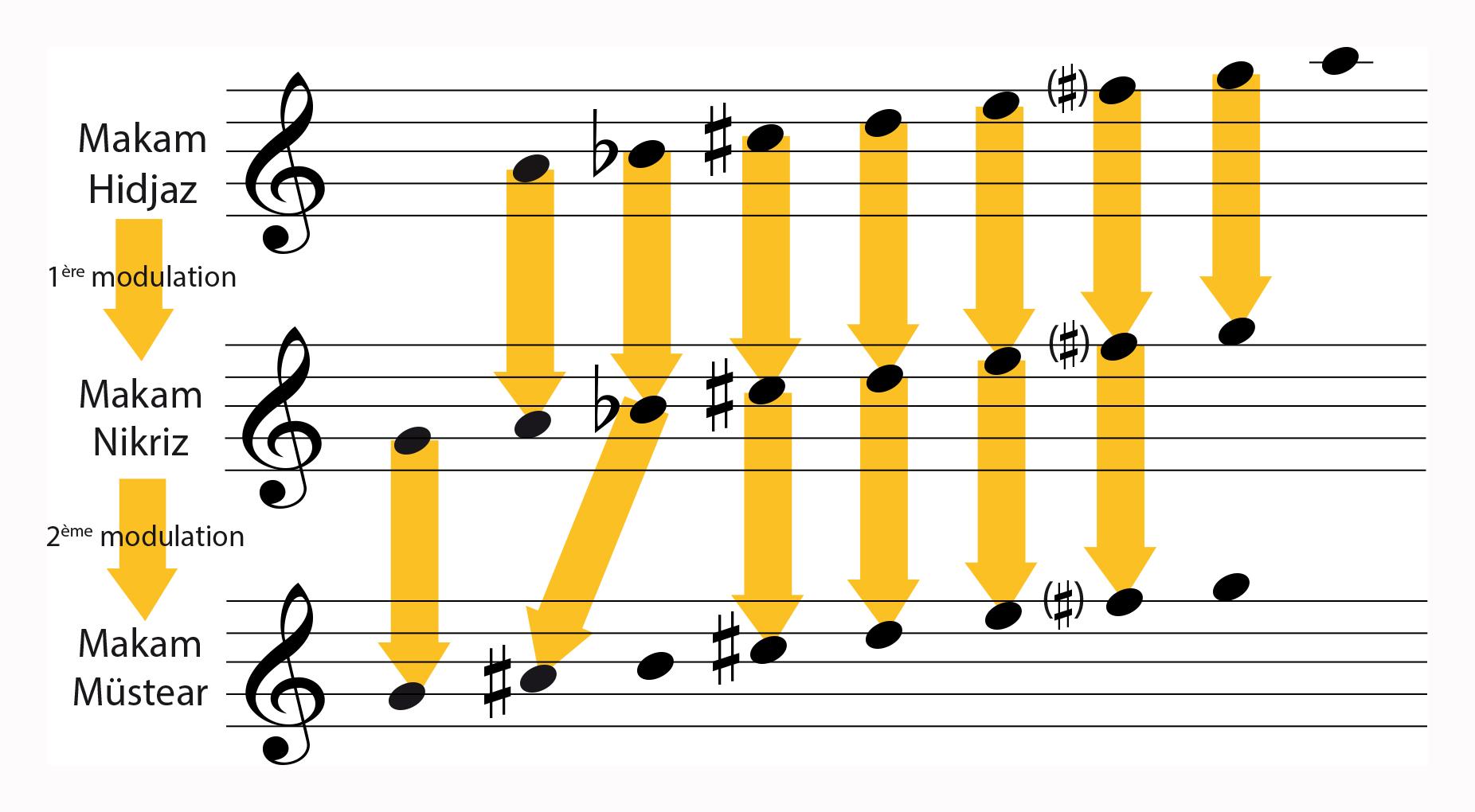

Here is an example with the Hidjaz makam as the starting mode, then a first modulation a tone lower in the Nikriz makam, followed by a second modulation in the Müstear makam on the same drone. The makams shown here are in equal temperament.

Modulations Based on Shared Degrees, by Laurent Clouet. © Laurent Clouet / Drom

The Importance of the Hijaz Tetrachord for Modulation

The Hijaz tetrachord, easily identifiable by ear, is the quintessential, instantly recognizable characteristic of Eastern music. Described in tempered terms, it is the sequence of intervals "a semitone - a tone and a half - a semitone."

In the Balkans, it is a key to modulation, which is why modes incorporating the Hijaz tetrachord are favored there.

Here, the makams are notated in tempered form for ease of understanding.

Modulation with the Hidjaz tetrachord by changing the drone:

If the drone (the tonic) is moved while keeping the Hidjaz tetrachord in the same position, one can move from one makam to another, as follows:

Modulation with the Hidjaz by changing the drone, by Laurent Clouet. © Laurent Clouet / Drom

Modulation with the Hidjaz tetrachord on the same drone:

If one remains on the same drone (the same tonic) but moves the Hidjaz tetrachord, one also moves from one makam to another, as follows:akam à l’autre, ainsi :